Why We Need More Poetry in Hospitals—and on Television

Poet Laureate Ada Limón's poem goes primetime on The Good Doctor

What can poetry do?

It can connect people, lead to real-world actions, and even function as a kind of weapon. It also, of course, makes us think and feel and see deeper than any exhortation to look ever could.

Poetry’s power to heal is one of its most frequent anecdotal uses, as well—think how often you’ve heard the act of writing poetry likened to “therapy.” But poetry’s actual healing power has begun to be documented in medical and scientific literature. Consider, for example, the abstract of Kwok et al.’s “Poetry as a Healing Modality in Medicine: Current State and Common Structures for Implementation and Research”:

In healthcare institutions across the country, the role of poetry continues to emerge within the liminal spaces between the medical humanities and clinical care… Poetry in the medical humanities literature has often been described by its indefinability as much as by its impact on healing… Poetry can be medicine for both patient and clinician. “Poetic Medicine” is a modality that has been utilized for the healing of grief, loss, wounds of the psyche and spirit, and as a process for expanding resiliency in healthcare-applications that are particularly relevant to the practice of hospice and palliative medicine-for patient and clinician alike.

It is this medicinal capacity of poetry as body-and-soul medicine that inspired a recent episode of “The Good Doctor” in which Poet Laureate Ada Limón’s “Instructions on Not Giving Up” hugely features. What results is not only a paean to poetry’s therapeutic power but also a masterclass in highlighting contemporary art and artists in pop culture.

The Greening of the Trees

In Season 6 Episode 18, “A Blip,” we meet a woman named Harper (Molly Griggs), who’s suffering from long COVID symptoms. In the course of her stay at the hospital, it’s discovered that she also has a rare heart defect that’s usually detected in infants—she’s lucky to be alive, but she’ll need surgery and her case is complicated.

Long COVID has damaged Harper’s executive function and plunged her into a brain fog. In a conversation she has with Dr. Lim (Christina Chang), Harper notes that she’s been reading and writing poetry as a way to exercise her mind after COVID:

HARPER: “It’s the greening of the—”

DR. LIM: My turn.

HARPER: I’m trying to get some of my cognitive exercises in.

DR. LIM: What are you memorizing?

HARPER: It’s a poem from The Carrying, Ada Limón.

DR. LIM: Hmm.

HARPER: The collection is mostly about... not having the life you thought you'd have, I guess. The one I was just reading, it’s about spring coming: “Instructions on Not Giving Up.”

DR. LIM: Sounds useful.

HARPER: Yeah. Too bad I can’t read it all at once. I’ve just graduated from haikus. I never even thought to look at a poem before I got sick. Didn’t have the patience for it at the time, but it’s basically all I read now. I started writing, too. It’s kind of a creative therapy.

When Dr. Lim enters, Harper is reciting part of a line from the middle of “Instructions on Not Giving Up”: “it’s the greening of the trees / that really gets to me.” Don’t worry—we’ll get the rest of the poem later.

What’s fascinating is the way in which Harper begins by discussing memorizing poetry as a kind of treatment of medical tool—a “cognitive exercise” designed as a kind of treatment for her long COVID symptoms—but quickly moves into more emotional and holistic territory by revealing that she reads poetry now almost exclusively and writers it, likening it to “creative therapy.”

Poetry is helping her recover bodily, but also mentally and emotionally. This isn’t just TV magic: the use of poetry to heal has real-world proponents, including The National Association for Poetry Therapy (their integrative medicine packet is fascinating) and practitioners of psychology, and others in medicine and medicine-adjacent fields.

It just so happens that Harper is using our current Poet Laureate’s work as part of her therapy. This is a big get for poetry.

The Strange Idea of Continuous Living

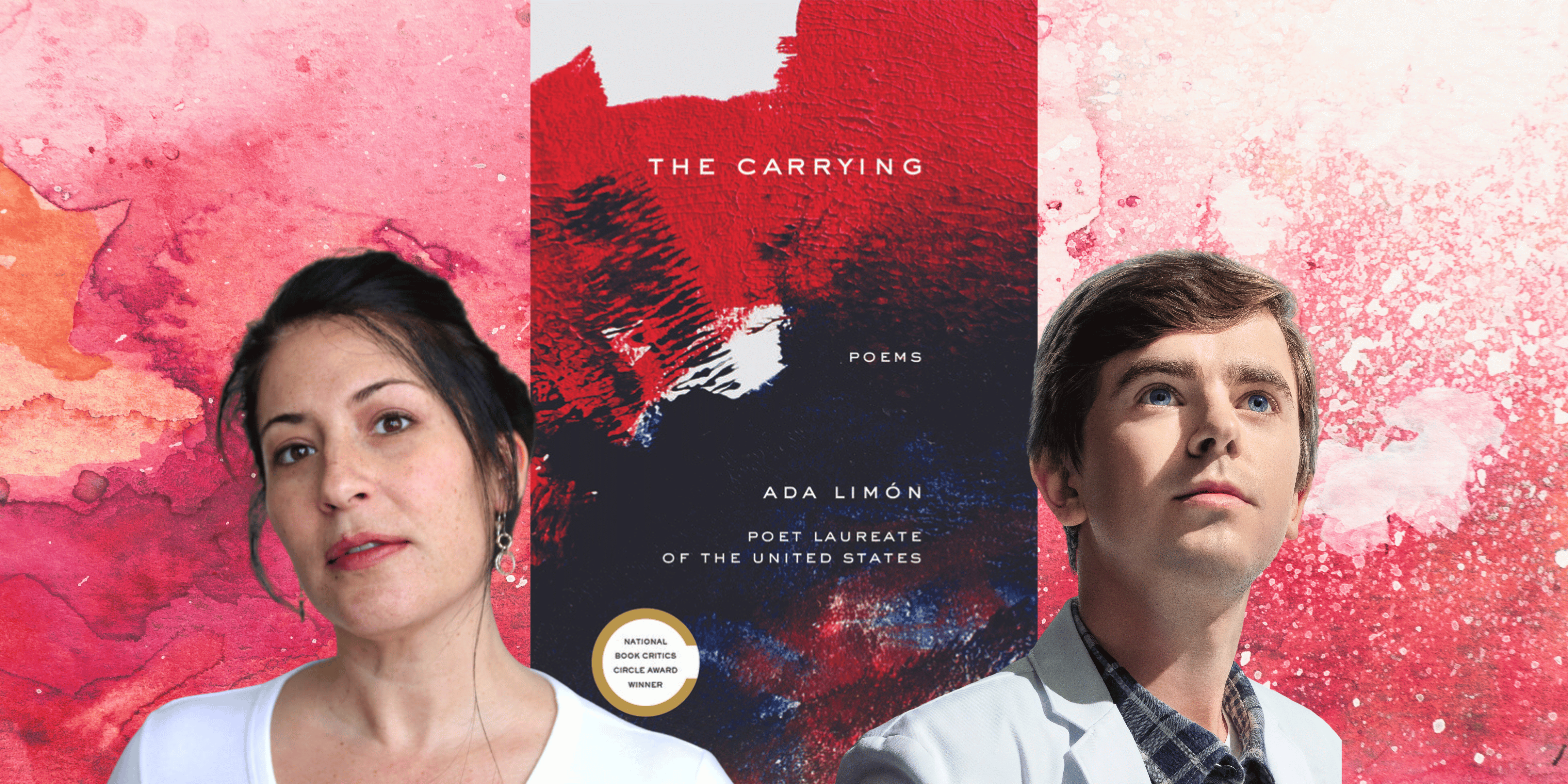

Far from just a passing mention, Ada Limón’s work is central to the episode and actually appears on screen in physical form. Very often, the actual art objects that poets create—the full texts of the poems and the books they appear in—are invisible. But The Good Doctor goes out of its way to show the actual object of a book of poems.

Unlike other shows that don’t show books of poetry at all or show bizarre, doctored covers of books that have never existed, The Good Doctor shows the full cover of Limón’s The Carrying. While it might be argued that as the Poet Laureate Limón already has a massive audience, we’re still talking about poetry, here. If Billy Eichner accosted folks in the streets to see if they could name the current Poet Laureate, the results would be grim, my friends. Grim. More exposure for poetry is always good for authors and for us as viewers and readers.

Showcasing the work of living writers is incredibly rare in the public (e.g., pop culture) eye. Showcasing the work of the living female writer of color is even rarer, even if she is the Poet Laureate (recently reappointed to a historic two-year term, I might add—she’s awesome).

I love seeing a book of poems in a hospital bed because that’s where they belong: in our lives as they are lived daily, not just on the moldering shelves of library basements, where students sometimes imagine that they live.

Poetry is highly portable, communicable, and shareable. It’s possible to pass around a book of Magritte paintings, but the full effect of the painting is best had when standing in front of the original. With poetry: each and every one of us can hold the “original” or official version of a poem in our hands by visiting a local bookstore in person or online. Poetry is easily accessed and being written by those around us who look like us. These are important lessons that this episode of The Good Doctor is imparting, if subtly.

What’s more, the poem itself describes the resoluteness of trees in springtime, who miraculously recover from the pain of winter and dare to burst into leaf again even though it is difficult and impermanent. Harper takes the poem’s advice deeply to heart and allows it to inform her healthcare decisions in positive ways. At the episode’s close, the entire poem is read out in voiceover, and its wisdom echoes throughout the lives of all the characters on the show. It’s just lovely. I want to watch more television episodes containing poetry by living writers, like this one.

The Confetti of Aftermath

The Good Doctor does a wonderful service to poetry in its portrayal of Limón’s poem. An actor speaks the name of the poem, the poet, and the collection the poem appears in. We also see the physical book and hear the entire poem read aloud. The poem is also very well integrated into the storyline of a character in the episode. As a poet, you couldn’t ask for any better press, and the argument that the show is making about the power of poetry to heal has large implications.

Poetry has been used as medicine both privately and publicly for hundreds of years, and though narrative medicine is a rather well-established field, the professional study of poetry in medicine remains an interesting and hope-instilling field. Poetry belongs everywhere that people are, and when people are not well, they find themselves in doctor’s offices, hospitals, and hospices. Poetry belongs there, too.

Do something therapeutic for yourself today and take the good medicine of Limón’s poem in its entirety. Drink it down:

Instructions on Not Giving Up Ada Limón More than the fuchsia funnels breaking out of the crabapple tree, more than the neighbor’s almost obscene display of cherry limbs shoving their cotton candy-colored blossoms to the slate sky of Spring rains, it’s the greening of the trees that really gets to me. When all the shock of white and taffy, the world’s baubles and trinkets, leave the pavement strewn with the confetti of aftermath, the leaves come. Patient, plodding, a green skin growing over whatever winter did to us, a return to the strange idea of continuous living despite the mess of us, the hurt, the empty. Fine then, I’ll take it, the tree seems to say, a new slick leaf unfurling like a fist to an open palm, I’ll take it all.

If you liked this post, you might also like…

This Is Us and the Case of the Disappearing Poet

Do you read and enjoy PopPoetry every week? Have you become a paying subscriber? If you appreciate the labor of love that it takes to bring this work to life, consider upgrading your subscription! Early subscribers get a great discount. This Is Us recently began its farewell …

Yes! More poetry in our public lives! What if we thumbed through a slim volume of poems instead of scrolling social media when we needed a brain brake?

oooof that's a good poem. And I loved the way you wrote about this episode, particularly this paragraph: "I love seeing a book of poems in a hospital bed because that’s where they belong: in our lives as they are lived daily, not just on the moldering shelves of library basements, where students sometimes imagine that they live."