This Is Us and the Case of the Disappearing Poet

Randall's namesake is a huge part of his story & makes a great case for the power of representation. But This Is Us showrunners stamped out the contributions of another important poet in the process.

Do you read and enjoy PopPoetry every week? Have you become a paying subscriber? If you appreciate the labor of love that it takes to bring this work to life, consider upgrading your subscription! Early subscribers get a great discount.

This Is Us recently began its farewell season. The tear-jerking, deeply felt, and widely acclaimed NBC drama premiered in September 2016, just before the United States was rocked by an infamous election that continues to echo throughout our lives. For the last six years, This Is Us has been a place where I go to feel things, to get in touch with things that bind human beings together in a time of deep divisions. And no matter how chaotic and disappointing the world around us is, the show celebrates the beauty that family life can afford in a way that still feels honest about how difficult our relationships with the people who love us can be.

This isn’t to say the show is perfect or depicts perfect families: matriarch Rebecca (Mandy Moore) denying her son’s birth father William (played by Ron Cephas Jones as an older man) the ability to have a relationship with him does not square with contemporary approaches, for example. The writers also waited five seasons to fully address the heartbreaks of racism within mixed-race families. But it’s more progressive than many shows dare to be and routinely takes up the topics of PTSD, addiction, body image, death, grief, Alzheimer’s, and more.

Before the show reaches its end, let’s look back to the beginning.

How Randall Got His Name

The third episode of Season 1 (“Kyle”) begins with a flashback of Randall’s father, William (played by Jermel Nakia as a young man) writing poetry on a city bus. As time passes, the poems William writes begin to take on a new subject: a beautiful woman he’s spied on his ride. We eventually learn that this is Randall’s mother, Laurel (played by Jennifer C. Holmes as a younger woman). Soon the pair are sitting together, and the poems keep flowing. But eventually, the pair looks less bubbly and newly-in-love and more strung out, exhausted, and unwell. We’re meant to understand that the pair have a growing drug addiction. As a result, we watch as William’s notebook becomes less coherent and more chaotic until William can barely turn its pages.

I appreciate this scene because it contradicts popular “tortured artist” stereotypes which hold that intoxication is some kind of prerequisite for artistic production. William’s addiction makes him less able to create, not more.

Later in the episode, we see young Rebecca boarding the same bus. She tells the driver that she’s looking for someone she knows very little about. She describes William in the most basic terms, but the driver catches on.

“Shakespeare?” the bus driver asks. He knows William and has given him a poetic nickname. Apparently, he tells Rebecca how to find him, because she later winds up on William’s doorstep.

Rebecca has come to see the man whose child she has adopted and is now raising. She is curious about William but has mainly come here for her own selfish reasons. She wanted to know if there “was love” where her adopted son came from, and William tells Rebecca that there was. He tells her that he used to read poetry to his son’s mother Laurel, who seems to have died after giving birth to him.

Rebecca admits that she and Jack (Milo Ventimiglia) named their three babies “on a whim” with the same K sound: Kevin, Kate, and Kyle. These were the names she’d picked out for her three biological children before she had even given birth to them, and so when her third triplet did not survive its birth, William’s son (now known as Randall) slid into a space already marked “Kyle.” It is, essentially, the name of a white child: a dead white child.

Before she leaves, Rebecca admits that she is having trouble connecting to her adopted son. This is a painful and troubling thing to admit to a birth parent, but William is not shaken by her confession. He offers her some advice:

WILLIAM: Give him his own name.

REBECCA: What was the name of the uh, the poet you used to read to her? Your favorite poet?

William turns and pulls a book from his shelf, and hands it to Rebecca. “Maybe you’ll see fit to give it to him someday,” he says. Rebecca thanks him, takes the book, and leaves.

Chekhov’s Gun Poetry Collection

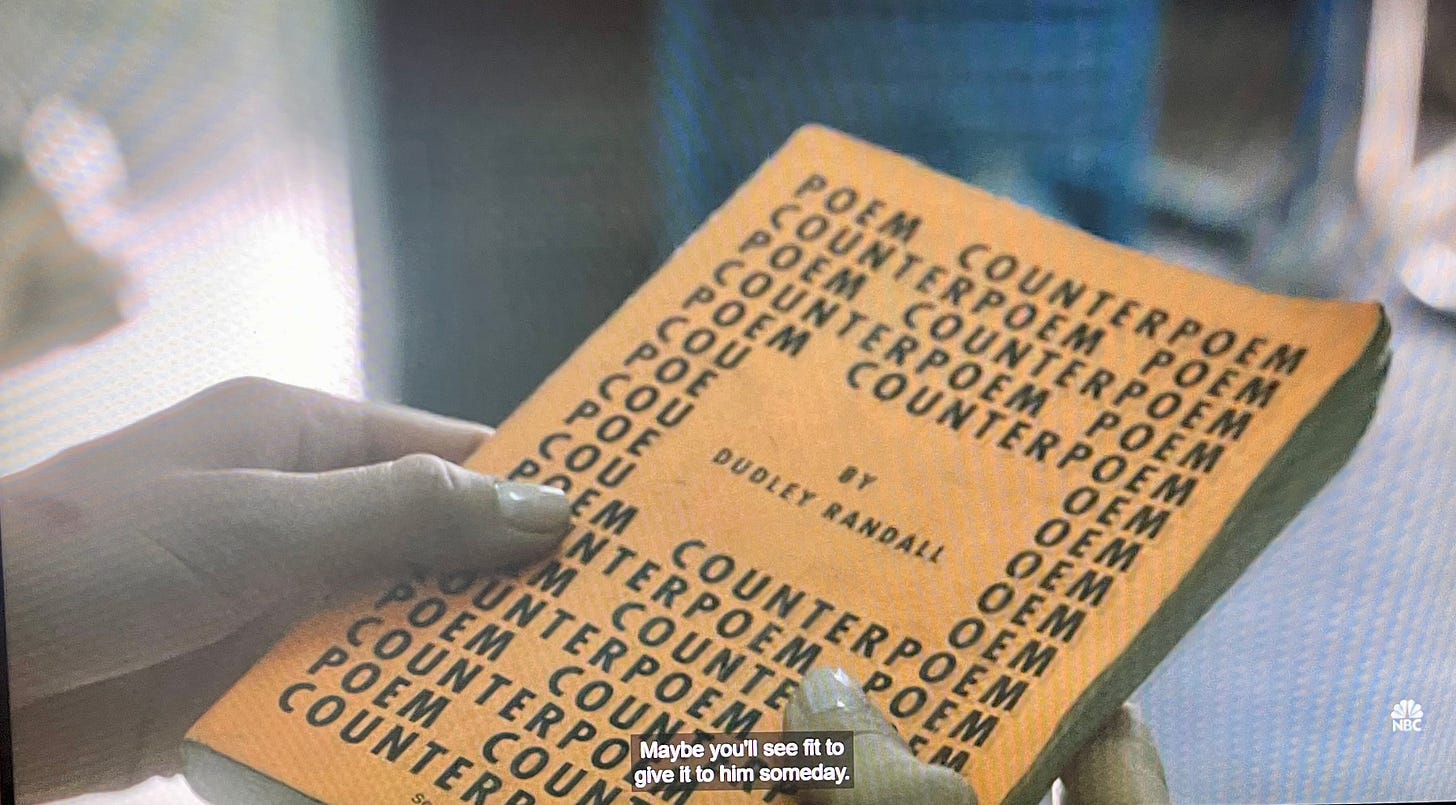

The book William hands Rebecca is Dudley Randall’s Poem Counterpoem (Broadside Press, 1966).

Or rather, Dudley Randall and Margaret Danner’s Poem Counterpoem. Fascinatingly, the copy shown in This Is Us has Danner’s name removed so as to make the book seem like a single-author volume of poetry.

I’d assume that the good folks in props elected to mock up the book as a single-author volume of poetry primarily to avoid confusion regarding the name that Rebecca would eventually give her adopted son. But how confusing would it have been, really? If they had left the names “Margaret Danner” and “Dudley Randall” on the front of the book, would we have assumed that the character who we already know is named Randall was named after Margaret Danner?

Removing Danner’s name from the book seems like a missed opportunity to make a subtle argument about the power of collaboration.

All but one of Dudley Randall’s books that he authored alone were published before the triplets’ birth year (1980), so the showrunners could have picked a number of other books to use as props in these scenes instead. Love You (1960) and Cities Burning (1968) would have been great choices because their designs scream “1960s” just as much as Poem Counterpoem, and the former even has a powerful photo of the poet on the front. (Plus, using a book called Love You in this scene about adoption? Come on! They should have asked me to consult.)

Part of me thinks that the showrunners or the writers or the prop designers or whoever was in charge of the decision have a special kind of reverence for books with one author. This is quite common in our culture, where individualism and the myth of the solitary genius are valued much more than collaboration and communal efforts to do just about anything, including making art.

Removing Danner’s name from the book seems like a missed opportunity to make a subtle argument about the power of collaboration. Like Poem Counterpoem, Randall’s place in the world, after all, is a collaboration between women and men too: Rebecca and William in his upbringing, and Laurel and William in his birth.

In another flashback later in Season 1 Episode 3, we watch as Rebecca hands the book to Jack and tells him that she thinks they need to change Kyle’s name. Jack takes the book, seems impressed, and nods. But where does he think the book came from?

That question is never answered, and we’re made to understand that no one, not even Jack, knew that Rebecca had visited William for 36 years. Later, in Season 1 Episode 7, an older William recites part of Dudley Randall’s poem “Luzon,” and Randall’s wife Beth joins in. He wonders how she knows the poem.

BETH: It’s in this book of poems that Randall’s had since he was a baby.

WILLIAM: Oh, yeah, that’s right. The one I gave Rebecca back in the day… oh.

BETH: What?

Dudley Randall’s poetry becomes the key to letting an enormous family secret—that Randall’s adoptive mother knew who his birth father was and had contacted him decades ago—out into the light. The adult Randall, formerly known as Kyle, is left to pick up the pieces of his past before our eyes.

Randall’s Namesake

Like Sterling K. Brown’s Randall, Dudley Randall was a man who brought people together and sought to improve not only his own circumstances but also the circumstances of others. Born in Washington, DC, Randall moved to Detroit when he was a child and would become the city’s first poet laureate. Randall worked as a reference librarian and also founded the influential Broadside Press, which exists to this day. Randall published the work of countless writers, including Gwendolyn Brooks, Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, Audre Lorde, Etheridge Knight, and others.

Randall held many esteemed positions throughout his life, including as a Poet-in-Residence at what’s now known as the University of Detroit Mercy.

It’s unclear whether Rebecca fully passed off William’s idea for Randall’s name as her own and told Randall that she named him after Dudley Randall, but in either case, Dudley Randall is a wonderful namesake for the Randall we know on This Is Us. His work, which often deals with Black identity and the struggle for liberation in all its forms, echoes Randall’s own questions about his place in the world.

Having a meaningful name makes you visible to yourself, in a way. And seeing people who share your background creating art and succeeding out in the world makes you visible to yourself, too. The This Is Us writers got this part right, but in doing so, they left out the contributions of another important Black artist.

The Missing Poet

Since Margaret Danner was erased from the book cover shown on screen in This Is Us, let’s not erase her here, too: let’s celebrate her.

Margaret Danner (1915–1984) was a poet and activist known for her associations with artists in both Chicago and Detroit. Part of the “Detroit Group” that was then vibrant at the time, her friends and colleagues included Randall, Naomi Long Madgett, Karl Shapiro, and Langston Hughes, who acted as her mentor and frequently corresponded with her. In 1956, she was selected as Poetry magazine’s first Black Assistant Editor. Danner also founded Boone House, a Black arts and cultural center in Detroit.

A great believer in the power of youth and future generations to usher in change, she authored six volumes of poetry during her lifetime and edited two collections of student verse. Poem Counterpoem, co-authored with Randall, was Broadside Press’s first published book.

Two of Danner’s poems from the October 1956 issue of Poetry illuminate Danner’s keen eye and her passion for African arts and culture.

You can also listen to Randall and Danner read from Poem Counterpoem via the Williams College Special Collections.

In a 1968 interview in Negro Digest, Danner wrote “I believe… that the Black should be awakened to his vast beauty.” This seems like something that Sterling K. Brown’s Randall could have benefitted from hearing as a kid, growing up in a white family that, while loving and attentive, doesn’t really understand how to care for his soul. But they gave him a small gift in the form of his name, which ties him to a legacy of Black poets and writers who he could look to for inspiration on his long journey back to himself.

P.S.

Maya Angelou is the first Black woman to appear on a U.S. coin! This is such a lovely tribute, but as always America is short on racial justice and long on symbolic gestures.

The luminous Amanda Gorman is in Vanity Fair and helping us commemorate our days with a poem once again.

![Poem Counterpoem [Signed] by DANNER, Margaret and Dudley Randall - 1966 Poem Counterpoem [Signed] by DANNER, Margaret and Dudley Randall - 1966](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ZgFm!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa8fb2288-bee7-4095-bc86-c68247283468_600x755.jpeg)