What Bridgerton Gets Wrong About Poetry in General and Byron in Particular

Benedict understands far more about poetry than Anthony does, but his distaste for Byron is a bizarrely played-out choice on behalf of the show's writers.

Do you write poetry?

If so, has anyone ever subtly (or not so subtly) suggested that what you do is frivolous? That the world has no use for “pretty words,” or something like that? I can see you nodding yes.

Though Shelley once proudly proclaimed that poets were the “unacknowledged legislators of the world,” poetry today holds relatively little stature either in the realm of politics or in the popular imagination, though things are changing (if glacially). The notion that poetry writing is masturbatory and serves no real purpose is alive and well, as evidenced by our constant impulse to reaffirm its value or convert haters of the art form. To write poetry is to be acquainted with its cultural connotations of futility.

We’re not safe from this tension even in our escapist media: Netflix’s steamy, sumptuous Bridgerton takes many liberties with its historicity, but it locates poetry’s hard-to-shake implications of uselessness with extreme accuracy.

Words vs. Deeds

Years ago, while having drinks at our favorite local bar, my ex-husband once asked me, cruelly, why I wrote poetry when it “doesn’t make any money.” His question resulted not in an answer, but in my throwing our car keys across the table at him and retreating to a different bar, alone. He only saw value in dollar signs, and could think of no other use for poetry in my life or in anyone’s life. His low regard for my writing is one of several reasons why he is now, mercifully, my ex-husband.

I know you have your own stories. The parent who keeps urging you to write YA or novels because they’re “profitable.” A friend who wonders why you didn’t just go to law school. A partner, who, while well-meaning, stares at their phone during your reading, waiting for the whole sordid affair of mere words to be over so they can get back to the business of actual living.

More so than fiction or nonfiction, the words that comprise poetry have been opposed to deeds, to the realm of action and getting shit done, almost as long as they’ve been written. This is a false opposition: alleging that an art form is useless merely because it is difficult or more obscure than, say, screenwriting, is nothing more than an attempt to silence those who would tap into its power. In his essay on W. S. Merwin and the language of war, poet Matthew Zapruder offers a consideration of poetry and politics—

I doubt whether any poem, no matter how great, will make any real difference in our political life. No matter what a poem says, I do not think it will even for a moment stay the hand that is about to pull the trigger, push the button, or sign the law. I don’t think that’s what poems are for. Sometimes poems remind us of what we already know but might have forgotten.

Poetry need not alter the outcome of an election to be good and useful and to make a difference. But sometimes it can actually incite deeds.

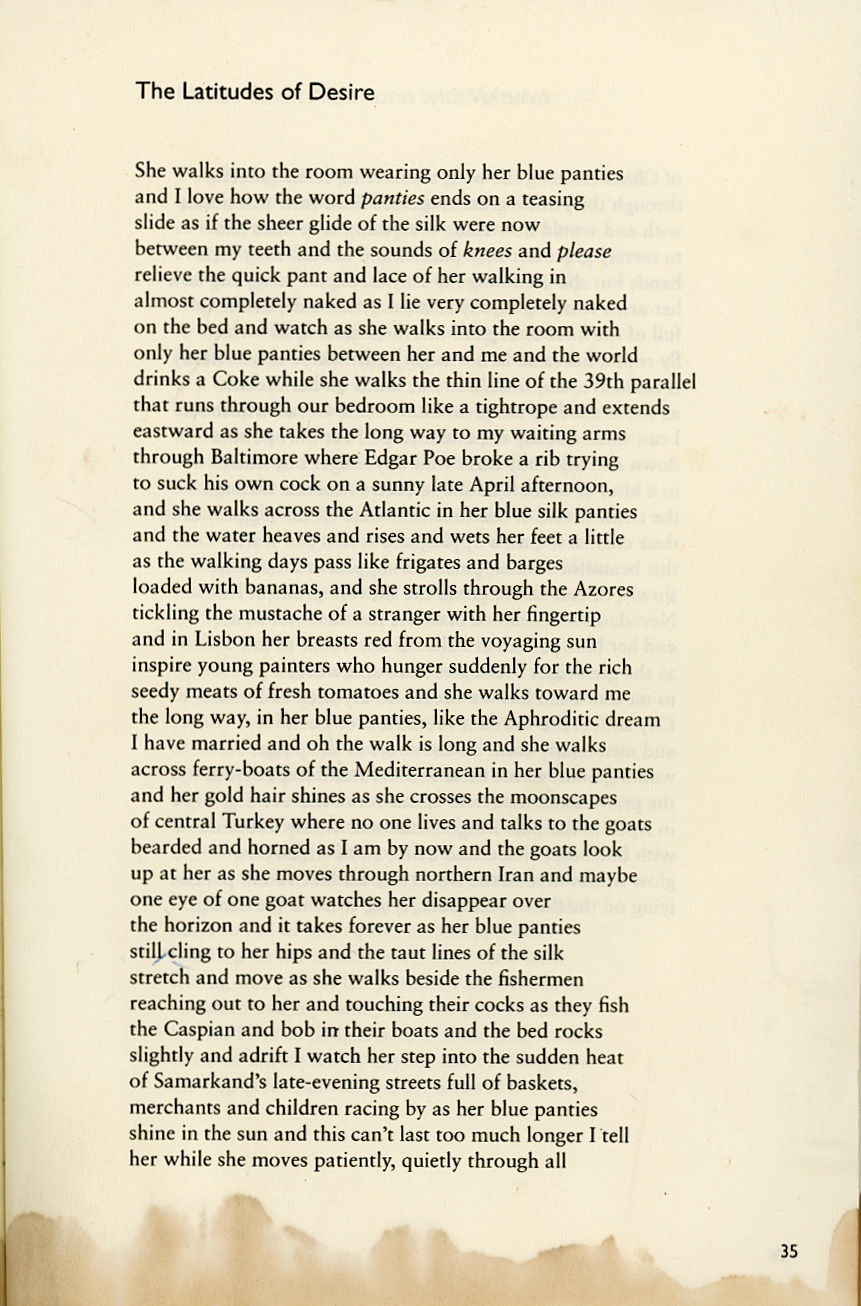

How’s this for action? Upon reading Steve Scafidi’s “Latitudes of Desire” for the first time, I was struck by the fact that the person I was married to would never be interested in reading a poem like this even if I asked him to, let alone the fact that he was someone constitutionally incapable of ever thinking of me as “the Aphroditic dream / I have married.” This thought tapped at my proverbial window for months while things deteriorated between us until, one day, I clambered over the sill and filed for divorce.

This is a true story.

I want to argue both that poetry does not need to provoke direct action in order to be valuable and that it also can and does provoke action, and not just on a personal scale. Though it might not be the kind of trigger-staying action Zapruder mentions, think of the important role that poetry played in Irish political movements. Or work written by Mexican women poets in the 19th century. Or in the wake of the Vietnam War. Or consider the fact that Bill Clinton, Joe Biden, and other politicians have looked to Seamus Heaney more than during their political careers. The list could go on and on—poetry has been political from its inception, and doesn’t have to directly incite immediate change in order to be valuable. Poetry is persuasive, humanizing, and resists the bullshit of propaganda and empty language. It brings us home to ourselves, to deeper truths, and therein lies much of its power.

And so, when Anthony Bridgerton dismisses poetry as mere “pretty words,” he is making a specious, simplistic argument to a massive audience. The show’s writers also have Anthony’s brother Benedict malign the work of Lord Byron for what amounts to Regency drama scene points. On a show like Bridgerton, there isn’t enough room for nuance to balance the strong opinions offered by both brothers about poetry more generally and Byron specifically.

Bridgerton vs. Byron

Lord Byron, one of Romantic poetry’s most prominent figures, pops up more than once on Bridgerton, and not always in favorable comparisons. Byron is a perfect fit for this soapy, sexy show not only because of his status as a Romantic poet but also because of his well-documented louche lifestyle. Early on, we get a little winking reference to Byron: Penelope Featherington implies that a certain suitor’s poetry is lacking by saying “Lord Byron he is not.” Though Penelope uses his name as an example of good poetry in Season 1, Benedict dismisses his work in Season 2.

Anthony asks artistic Benedict for his help in order to recite some of Byron’s poetry as a way to woo Edwina Sharma. Benedict refuses, not because he dislikes poetry, but because he believes Byron’s work to be “nonsense” and boasts that some of his friends at school often preferred Benedict’s own poetry to Byron’s.

As it turns out, looking down on Byron, whose work was well-known in his own time, is a staple trope of regency period dramas. But the disparagement of the poet usually comes from gentlemen who are turned off by anything that might possibly be construed as effeminate. In the Season 2 reference, Benedict, the “queer-coded” Bridgerton brother, does the dissing—a weird choice by the Bridgerton writers.

Vox culture reporter Aja Romano does an excellent job of explaining this blundering Byron hate in context.

Anthony presses on anyway, and begins to breathlessly practice some lines from Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1818). The poem describes what’s now known as a Byronic hero, who sojourns and contemplates in the natural world on a quest for beauty and enlightenment. This is not the kind of man Anthony is publicly… but is it the kind of man he secretly longs to be? We get the sense that part of the eldest Bridgerton brother wishes he could give it all up and live a freer, more artistic lifestyle like that of his spurned lover, the opera singer Siena.

In any case, Anthony’s attempts to recite the poem well fall apart, primarily because he doesn’t really believe that poetry has value or can get him what he wants.

Benedict, an artist himself, understands poetry better and seems to take its power for granted. He’s shocked when Anthony refers to poetry’s primary objective as deceit. “Deceitful?” He asks. “Poetry is the opposite, brother. It is the art of revealing precious truth with words.” While Benedict does take a moment to improve Anthony’s definition of poetry, here, he doesn’t ultimately challenge his brother’s opposition of poetry and action.

Anthony doesn’t really take the meaning of Benedict’s words to heart, instead fixating on the poetic quality of what his brother said. It’s maddening. “Write that down!” he says. Later, Anthony attempts poetry reading for his assembled guests, jettisoning Byron for the words of his own brother, which he at first tries to pass off as his own.

But partway through his performance, Anthony gives up altogether and admits that he’s just not that kind of guy. He’s more into deeds than words (that false opposition again). To his mind, poetry is nothing more than hot air. As a man of action, he finds it useless to use mere words to woo a woman. Edwina is (disappointingly) charmed by his frankness and his admission of his own deficiencies. We are left feeling that perhaps poetry is mere hot air, and that Byron is a shining example of the worst kind of hot air. Neither are true, but it would be easy to passively accept these notions as a casual viewer of the show.

Luckily, you have me to rant and rave about the other side of the coin. The utilitarian view of poetry—namely, that it is useful only as a means to an end—is risky and reductive. One hopes that the Bridgerton brothers’ words, in this case, do not lead to action, and lead viewers, instead, back to poetry rather than away from it.