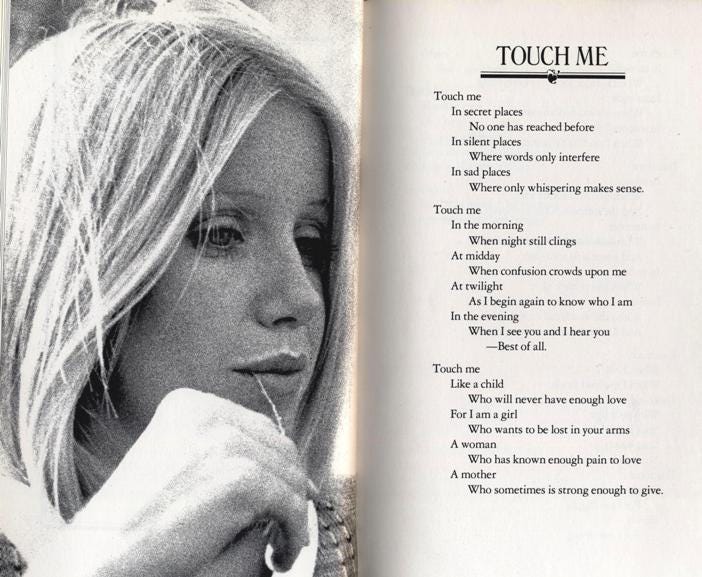

Touch me.

It’s a phrase loaded with sexual passion, an imperative sentence that asks the hearer to put down language and take action instead. Touch me. Do it. It’s as much a dare as it is a demand. We know exactly what it means, and why we say it, but hearing it aloud or seeing it written down feels inexplicably raw. It’s like a secret said aloud.

We’re more in tune with what it means to be touched than ever in this cultural moment: in the wake of pandemic-induced isolation and loneliness, studies abound which show that so-called touch starvation or “skin hunger” can damage our immune systems and increase anxiety and depression. At the same time, parents (and particularly women) are naming the experience of feeling “touched out” by their children, many of whom are at home more often with the rise of working from home, airborne illness, and childcare shortages.

Touch, then, is a continuum. We want some, but there is a limit. Not all touch is good and beneficial, but without it, we wither. We need it, but asking for it makes us feel so vulnerable we often choose to keep our mouths shut about it.

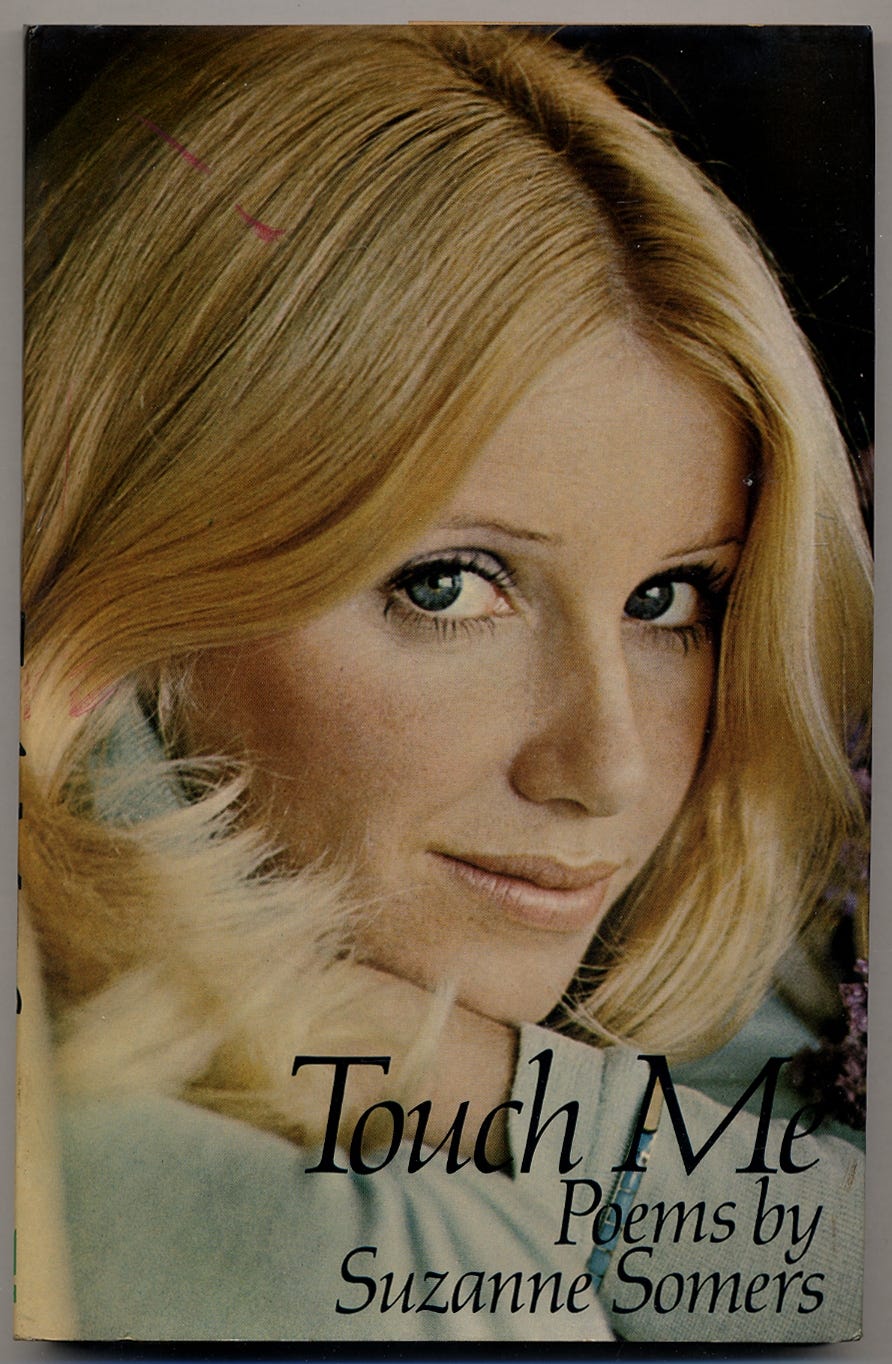

Suzanne Somers—actor, spokesperson, and author of numerous self-help books and autobiographies—is well acquainted with the naked fact of our bodies and their desires. She’s made a living from her body and from the desires of others to touch her and later became known for her controversial opinions about health and the body. But it is her having written a collection of poetry called Touch Me in the early 1970s that seems to be among her chief offenses.

Punching up is fine by me: Somers is wealthy and successful today. But the woman who wrote this volume of poetry was young and not yet famous. Even I sort of wanted this volume of poetry to be completely devoid of value, but as it turns out, there’s something there.

And isn’t there always? Isn’t there always a human on the other end, wanting—write it!—to be touched?

Somers the Woman

We love celebrity books of poetry around here. But Jimmy Stewart, Jewel, Billy Corgan, and James Franco released their verse volumes long after they had become famous. Suzanne Somers is unique among her compatriots, here, because Touch Me was published before she became a household name. It was her poetry, in fact, which led to other things. For a time, Somers even thought she would write poetry books for a living.1

Many readers and reviewers are fixated on the timing of the book’s publication, latching on to the fact that it was written before Somers was famous as if it somehow makes it ok. Fame seems to taint the books for readers even as they gobble them up. I’m more inclined to agree with Major Jackson in his Harriet blog post about celebrity poetry for the Poetry Foundation in 2008: “Do [celebrity] poems advance the art of poetry? Probably not, but they also do not poison the meal.”

Some readers and reviewers have also suggested that Somers’ poetry is not meant to be taken seriously. Jessie Gaynor of Lit Hub writes, “I think Suzanne Somers knows this shit is funny. I don’t think you can write a poem about the universal yearning for love with an iconic dig at dog people without a sense of humor.”

As tempting as it is to believe, I don’t think Somers’ poetry demonstrates an understanding of her own campiness. I think she wants us to read her work earnestly, just as Jimmy Stewart seemed to. In the forward to the 1980 edition (pictured in the Tweet below), Somers writes:

Touch Me is the cry of every voice, of trees and animals, women and men Touch Me is the call of all life, the challenge to death, and to touch and be touched—personally, intimately, honestly—is to live.

Trees. Animals. Women. Men. Life. Death. Somers is deadly serious. It’s difficult to look this much vulnerability and earnestness in the eye. It’s much easier to laugh at it. And there are moments when Somers catches you off guard with what seems like humor.

We want Somers to remain only a body, only a bimbo.

It’s this dimension of the work that Kristen Wiig latched on to in a video that began circulating again in 2020. Back in 2009, Wiig offered a dramatic reading of Somers’ book in order to garner laughs.

And to be clear, Wiig joins a long lineage of folks poking fun at the author-turned-actor-turned-lifestyle-writer. Tony Kornheiser’s inexcusably mean and nearly inarticulate 1979 profile of Somers for The Washington Post sums up the cultural estimation of Somers. He uses the word “airhead” twice, and not just to refer to Somers’ portrayal of Chrissy on Three’s Company, a character whose vapidity was so trenchant that it has colored opinions of Somers for decades since. But one section, which includes a quote from Alan Hamel, Somers’ husband, stands out:

Somers is big bussiness [sic] now but during her no-business days, she first began writing poetry. Hamel thinks that “she just decided she’d like to express herself in some other area other than superficial picture-taking. I doubt she anticipated it being published.” This was the time in her life when she truly was selling her face and her body. There are no words. At all in modeling. She was a woman being hit on and hit on and hit on. It may well have led to the poem, “No.”

Touch Me, then, may have been Somers’ reclamation of her body through text. Touch me, but on my terms. This is important work, isn’t it? But we want Somers to remain only a body, only a bimbo. But Somers’ reclamation would eventually go too far.

Her Thighmaster was anodyne and easy to dismiss; Somers’ later views on physical and mental health have proven to be much more dangerous. As she morphed from a perky sitcom star into an infomercial queen, Somers came under fire for her views on medical subjects. These range from easily dismissed granola-y musings, like her idea that the Sandy Hook shooter was harmed by “toxins” in household cleaners, to support for alternative cancer treatments and controversial bioidentical hormone therapies, for which she has been criticized by healthcare professionals and the American Cancer Society.

Is it possible to sever Somers the actor from Somers the poet? Does she want us to? And what does it mean when the airheaded doll speaks? Is it just easier to hush her up?

Somers the Poet

Few critiques of Somers’ book center on the quality of the poems and focus instead on who she is: a blond, wealthy, successful actor who became famous for playing a “bimbo” on television. Because we perceive poetry to be the ultimate act of self-making or self-actualization, a “failure” of poetry can too easily be equated to a negation of the poet’s entire identity.

If you’ve hopped down here to read the verdict about the poetic craft of Touch Me, it’s this: it ain’t good, folks. The spirit is willing, but the flesh—erm, the technique—is weak. Here’s why:

The poems attempt an air of wisdom but are often immature.

The poems in this volume are as naive and simplistic as the first fumblings of middle school poets attempting to find their voice and write about enormous, abstract topics like love in huge, sweeping statements. There’s nothing wrong with this, except for the fact that most juvenilia is never published, and many novice poets hone their craft for years before ever publishing a single poem, let alone a book. In this regard, her work is neither worse nor better than the so-called “Instagram Poets” of our contemporary moment, like Rupi Kaur or Charly Cox.

Somers overdoes it often.

There’s a picture of her in pigtails next to the poem “Sometimes I Want to Be a Little Girl.” There’s a poem called “The Quiet Loneliness of Being Alone.” We got it, Suz! Damn!

It follows certain poetic conventions seemingly just for the sake of doing so.

We’re capitalizing the first letter of every line and we’re rhyming and we’re breaking lines in the most obvious places and we’re speaking in high abstraction and it all feels very familiar. Nothing new here.

The personal doesn’t rise to the level of the universal.

One gets the sense that Somers’ poems have been immensely gratifying for her to write, but often the reader is left out in the cold. It’s a bit like hearing snippets of an intimate conversation at the next booth, then losing interest and returning to your drink.

The book’s central project is to help readers know Somers, not themselves.

In this, Somers is not unique. When it comes to celebrity books of poetry, most reviews center on the question of whether or not the celebrity should have been “allowed” to publish the volume in the first place (of course they should), whether or not their celebrity is the “only reason” the poetry was published (of course it is), and the timing of the publication in the celebrity’s life.

The book succeeds in a memoiristic dimension but ultimately lacks the qualities that make poetry great: image, metaphor, attention to language, surprise, meditation, and deep cognition.

Pop Palate Cleanser: You Can Still Touch Me

Reading this collection brought to mind two excellent examples of Somers’ ultra-vulnerable exhortation—“touch me”—that demonstrate what makes good poetry so good.

“Touch Me,” Stanley Kunitz

The same directive that Somers offers, in different hands, leads to a vastly different result. Stanley Kunitz’s “Touch Me” takes on the same themes as much of Somers’ poetry but meditates deeply on the nature of love and attraction in ways that the actor doesn’t. Where Somers is concerned with her desire, Kunitz thinks about desire more broadly and more maturely. Notably, he also speaks in images where Somers prefers easily generalizable abstractions:

I kneeled to the crickets trilling underfoot as if about to burst from their crusty shells; and like a child again marveled to hear so clear and brave a music pour from such a small machine. What makes the engine go? Desire, desire, desire.

The ending of this poem, without fail, always gives me the chills.

“Carwash,” Henri Cole

Henri Cole’s “Carwash” begins in a very quotidian fashion, as many of Somers’ poems do. But the dedication to image, language, and gut feeling makes this poem a stunner.

In the corridor of green unnatural lights recalling the lunatic asylum, how can I defend myself against what I want? Lay your head in my lap. Touch me.

Check out the video at about 28:07 for a bit of this.