Welcome to the first installment of All That Glitters: (Re)appraisals of musicians, actors, and other culture-makers who have written and/or published poetry.

All That Glitters is a semi-regular feature of PopPoetry, a poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. Check out the archive to see other TV shows, movies, and films whose intersections with poetry I’ve covered. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post! Come on… let me be your wild horse.

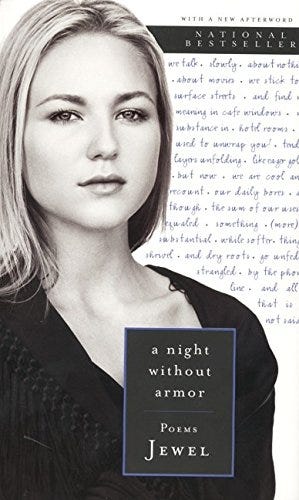

Recently there have been several reappraisals of the way that famous women have been treated by the media: Britney Spears, Whitney Houston, Jessica Simpson. It might be time to add Jewel, the four-time Grammy-nominated platinum singer-songwriter, to this ever-growing list. Not because her music was maligned, but because we spent so much time cracking jokes about her 1998 collection of poetry, A Night Without Armor.

In particular, I’ve been stunned anew by revisiting the behavior of MTV’s Kurt Loder during interactions with Jewel around the time of her book’s release. Loder, who was already the elder statesman of MTV when I was a kid, not only treated the world to palpable misogyny in these promotional spots but also espoused some truly nonsensical and simplistic “views” on what poetry is and can be.

Origins

I used a GIF from 30 Rock as the very first placeholder post on this site last year. The question Liz asks in the Season 6 episode “Today You Are a Man” isn’t a joke about the quality of Jewel’s book, it’s just a reference. She seems legitimately convinced by Jewel’s poetry, and implies that she agrees with the idea that emotion can be a weapon.

In short, she takes her seriously. And it’s funny because the opinion is controversial.

Yeah—Liz Lemon: hater of dogs and sandals and weekday sex and other good things. But she does love Jewel’s book, which is supposed to be funny because it’s considered to be a mediocre collection of poetry in the culture at large. I find Liz’s love of A Night Without Armor very endearing: the image of Liz reading Jewel’s spare verses about love and longing and feeling a little verklempt is charming.

Various misunderstandings of free verse poetry and misogynistic gatekeeping in the late 1990s, particularly by Kurt Loder, helped to create the “Jewel’s poetry is garbage” narrative that we have today.

Various misunderstandings of free verse poetry and misogynistic gatekeeping in the late 1990s, particularly by Kurt Loder, helped to create the “Jewel’s poetry is garbage” narrative that we have today. While it may not be the epitome of high literature, the book is certainly not as unreadable as it’s made out to be. Loder treated the then-23-year-old’s book with a disdain it doesn’t deserve when it was released, and his critique reveals his extremely limited understanding of what poetry is and can be.

Literary vs. Genre: A Refresher

In fiction, there exists a sometimes-useful-yet-rightfully-disintegrating distinction between “literary” and “popular” forms.

On the one side, you have what’s known as genre fiction or popular fiction: stories and novels that fit into already established genres that readers are familiar with and that adhere to certain or several conventions of that genre. Think sci-fi or A Song of Ice and Fire or romance novels designed to appeal to those who like romance novels.

There’s also literary fiction, which isn’t as easily classified. One could say that literary fiction is anything that is not genre fiction, but the term literary fiction also connotes intellectual difficulty, excellence, and seriousness, for better or for worse. This poses a problem because much genre fiction is challenging, wonderfully written, and serious in tone. But if it helps to hold an over-simplified example in your mind for the moment, think of contemporary works like Zadie Smith’s White Teeth or older works like Austen’s Pride & Prejudice when imagining what literary fiction is.

However, the so-called genre fiction vs. literary fiction debate is now commonly understood by many to be a false dichotomy. Lady Chatterley’s Lover contains many aspects of good romance novels, for example. By the same turn, to classify Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower as science fiction as a way to deride it would be to miss the brilliance of this incredibly important and well-written work.

So if genre fiction and “popular fiction” are well-understood terms, is there such a thing we might call genre poetry or popular poetry?

I would argue that there is, but we don’t have a name for it, in part because it’s so new. We’ve seen an explosion of “popular” poetry in recent years. Poets like Rupi Kaur, Courtney Peppernell, and Rudy Francisco sell more books than some literary poets will sell in a lifetime. Just peruse the aisles of chain bookstores and box stores today and you’ll find poetry there, but not by the kind of dead white authors you read in high school. The internet has also increased the reach of these so-called “Instagram poets,” who are either killing or saving poetry, depending on who you ask.

Jewel’s book is of a piece with these wildly popular, bestselling poets-of-the-moment. I confess that much of this kind of poetry does not resonate with me, but nonetheless, I think it’s silly to dismiss it out of hand. It’s here, it’s making countless people (and particularly young people) feel feelings, and that, to me, means it’s worth looking at more closely, which I plan to continue doing.

Just as critiques of slam poetry often engage thinly veiled racism, I find that critiques of poets like Rupi Kaur and Jewel (at the time) are often sites of poorly hidden misogyny. Writing about love, relationships, and longing (core themes of much Instagram poetry and Jewel’s book), and particularly such writing by women, is classified as drivel more routinely than work by men that engages similar themes.

I’m not arguing that Jewel’s work is literary. What I am arguing is that critiques of her book reflect a disdain for popular writing, a misunderstanding of what poetry is “allowed” to do.

I’m not arguing that Jewel’s work is literary. What I am arguing is that critiques of her book reflect a disdain for popular writing and a misunderstanding of what poetry is “allowed” to do. These attitudes are often accompanied by a helping of misogyny, too: by the pervasive cultural belief that the ideas, feelings, manner of speaking, and preoccupations of young women are fundamentally unserious. And nowhere was that made more manifest when it comes to A Night Without Armor than on MTV News coverage.

The Condescension of Kurt Loder

In 1998, Jewel sat down with MTV News correspondent Kurt Loder to talk about her then-new book, among other topics. The network also ran various spots to support the book, like this one, packaged and anchored by Loder himself:

Every time I watch this, I feel the actual warmth of rage. From the get-go, Loder does everything he can to telegraph his distaste for the book and for Jewel herself.

The first few seconds of the video are clipped. But we see Loder hold up a copy of the book by Jewel, who, he says, is known for her “yodel-y folk-pop stylings.” I think it’s safe to say that the term “yodel-y” is not a term of endearment anytime it’s used, and here it’s a dig at her unusual singing style. He says that she “published a book called A Night—that’s ‘Night’ with an ‘N’—Without Armor.”

Yes, he could be clarifying the homonym for viewers and listeners, but part of me wonders if he’s shaking his head at Jewel’s play on words (Knight Without Armor is the name of a 1937 Marlene Dietrich film). Coupled with the intimacy of evening, Jewel’s title hints at “unarmored” writing that lets the reader in. Personally, I think it’s cute. Loder is less sure.

How do I know this? His next instruction to viewers is, “You… may want to sit down for this.”

?????????????????????

Why, Kurt? Why will I want to sit down for what I’m about to hear? Is it because you think it’s foolish and silly? Offensive? Why would I need to be prone to hear Jewel talk about her poetry?

Unsurprisingly, what comes next is very tame. Jewel talks about how poetry is her “therapy,” and talks about her writing process, reaching people through poems versus songwriting, and the like. Clips of her songs are played, then she reads some of her poetry. It’s standard promo fare.

Then, Loder reads what he calls his “favorite” poem from the book:

JUNKY

mamma says she knows what

i’m gonna grow up to be.

Loder reads the line break by saying the words “new line.” Again, rather than trying to explain something written (a poem in hard copy) in a visual and audio format (television), it feels like an insult to Jewel’s aesthetic choices.

After he’s finished, Loder issues his pithy critique of the poem: “They used to call it prose.” He snaps the books shut with a hint of smug satisfaction, then moves on to the next segment.

I guess Loder wasn’t familiar with Aram Saroyan’s minimal poems, Eileen Myles’ narrow-stanza’d narrative style, or the “fuck it all” shotgun blast of e. e. cummings’ synesthetic visual poems. If this poem is the wildest shit that Kurt Loder has ever seen in poetry, then he hasn’t read any poetry whatsoever.

A white man so thoroughly entrenched in his privilege that he once stated that he “just fell into” journalism, Loder also noted that his “entire journalism background is four weeks... That’s it. Nothing else. You can learn journalism in four weeks. It’s not an overcomplicated thing. It’s very, very simple.” Ok. Cool. This is the guy.

This is the guy who gets to critique this young woman’s book on television to a youthful audience. If Loder’s brief was to try to make Jewel look naive and stupid, he may just have succeeded.

But whether or not you like the book now or then, Loder is engaging a facile critique of free verse poetry in terms of its form.

When he quips that “They used to call it prose,” Loder is taking issue with the plainspoken nature of Jewel’s first-person narrative poetry. The distinction between a poem that pays deep attention to the line as a formal consideration and a poem that proceeds in what some have called “chopped-up prose” is, in many instances, a kind of antiquated argument born out of the fear of free verse (which has been around since the late 19th century). My feeling is that dismissing something as chopped-up prose is just a way to deride the work of someone who is less interested in the line than in other considerations.

It may also be a feature of the work of a less mature poet or one who is still finding her voice, too (perhaps like the first book by a self-taught 23-year-old singer). No matter what the case, Loder summarily deciding that Jewel has written prose is a gross manipulation of the work she’s presenting. And it gets worse from there.

The Interview & Its “Casualty”

All the links that I find to the actual video of Loder interviewing Jewel about the book in 1998 are dead. The Wayback Machine is no help. It feels like it’s been scrubbed from the internet.

What we do have is a transcript of one of the tensest moments from the interview, which can be read here. I’ve also copied it and cleaned it up below for ease:

LODER: There's a line you have… “There are nightmares on the sidewalks / there are jokes on TV / there are people selling thoughtlessness with such casualty.” Casualty doesn’t mean that, does it? Casualty’s like a guy gets his arm blown off. I mean isn’t that...

JEWEL: That’s a type of casualty.

LODER: What?

JEWEL: It’s a type of casualty that...

LODER: No, really. I thought you were trying to say casualness.

JEWEL: No, casualty.

LODER: Oh, OK. All right. Are you a tech person? Do you take computers on the road, do you log on, e-mail?

JEWEL: No, I’m a bit archaic.I mean, I still write everything by hand. It’s quite archaic.

LODER: Wow.

JEWEL: It is wow. I’m dyslexic as heck. I mean, I just can’t type well.

LODER: Really? That’d be a problem for a writer.

JEWEL: It is a bit of problem. I mean, putting the book together. Everything was done by hand. I had to recopy it legibly to get it...

LODER: That explains casualty probably.

JEWEL: That probably does. [You’re a] smart-ass for pointing that out. Next topic.

LODER: I don’t know. I just want to help.

JEWEL: Publicly… If you wanted to help, you could have taken me aside, in a little corner.

Paging Every Guy in Your MFA, your shitty table is now available. I mean, seriously. Here’s a thought: How about we, as a culture, stop trying to ensure that our words mean what we think they mean and start treating other folks’ subjectivities as sovereign? I could do a reading so close that this interview would walk away with toilet paper squares stuck to its chin, but suffice to say that Loder is cruel in this interview. He leverages her dyslexia as a way to bring the conversation back around to his point about her word choice.

I could do a reading so close that this interview would walk away with toilet paper squares stuck to its chin, but suffice to say that Loder is cruel in this interview.

This isn’t a creative writing workshop: this is a promo tour for a published book. This is an established journalist who is 30 years the poet’s senior quizzing her on diction on one of the most-watched shows on television. And even if this were a workshop, let’s take a page from Felicia Rose Chavez’s endlessly luminous and powerful and correct as hell book, The Antiracist Writing Workshop, and stop inflicting our (white, patriarchal) tastes on writers and start asking them how we can help them achieve their writing goals. Instead of urging them to conform, the goal of workshop should be to help the writer find her own voice, not replicate yours.

For the next 20 years, A Night Without Armor would be the butt of jokes.

Young Women and the Men Who Chide Them

The idea that young women and female-identifying teenagers are fundamentally unserious creatures is at the heart of this mess, as well. While the tastes of young women dictate an enormous swath of consumer marketing, the feelings, attitudes, and actions of young women of all races and socioeconomic strata are subjected to stereotype, scorn, and derision.

Though she was young when she rose to fame and published her first collection of poetry, Jewel’s foray into poetry wasn’t a new phenomenon in and of itself: Patti Smith and Joni Mitchell did so successfully as well. The singer acknowledges poetic and musical ancestors in the book’s preface, and Joni, Dylan, Tom Waits, and Leonard Cohen all get mentions, as do Dylan Thomas, Shakespeare, Rumi, Yeats, and others.

The girl has done her homework and joins a long tradition of singer-songwriters who turned to poetry at one point or another. But men in particular have a lot of vitriol for Jewel and the audacity of her book’s existence nonetheless. That she dares to exercise her voice is an affront to men who think they know better what poetry is and wish she would just stick to making records.

A stroll around the internet turns up countless male critiques of Jewel’s book that are filled not with detached, objective criticism but with genuine anger. Dennis Cooper’s scathing, poorly-conceived critique of Jewel in SPIN boggles the mind. It’s not so much a critique as a take-down. “What has poetry done to deserve this?” Cooper muses. He offers up a woman he considers to be a “real” poet instead: Elaine Equi. While wonderful, the existence of Equi does not preclude the existence of Jewel. Both can exist. The pie is infinite, as I so often remind myself.

There’s plenty of male hatred for Jewel to go around. American slam poet Beau Sia even composed a book-length parody of Jewel’s book, complete with imitation artwork for the cover. Writer Jason Diamond attempted to critique Jewel’s book just to have the piece turn into a screed against an ex.

But the fact of the matter is that the book is not as bad as it’s made out to be. There are poems that bloom into these beautiful little vignettes. There are some poetic techniques: anaphora, metaphor, allusion. There are small details like a stick of licorice, a quiet hotel room above a bustling party… little windows through which I can see a young woman that I feel something for.

If A Night Without Armor were published today, it wouldn’t have been ridiculed to the same degree. I think it’s actually more aesthetically engaging than most of the Instagram poetry I come across these days.

Kurt Loder, in particular, owes Jewel an apology for his treatment of her and her debut book of poetry. His paternal cruelty seemed to bring him joy and satisfaction and is a prime example of the problematic way that we’ve showcased young women in the media in the past.

When we insist that poetry is for the few and the elite, we do poets and their readers a disservice. If we’re able to embrace popular poetry, or at least give it a sisterly side-hug, who knows what legions of readers might flock to the art form in years to come. The future is multiple, multi-vocal, many-gendered, and multicultural.

The pie really is infinite, and I hope that books like A Night Without Armor continue to find their readers so that everyone can feel that poetry is for them, too, because from where I’m sitting, it certainly is.

P. S.

In my latest publication at The Rumpus, I slipped a Frasier reference into a tough, personal poem about loss. Studies show that rewatching old shows is genuinely comforting and has positive psychological roots.

Smithsonian Magazine is talking about the migration of poetry away from academia, too.

Have you published a poem that engages with popular culture in a meaningful way? I’d love to chat with you, and I might even translate our conversation to an interview on PopPoetry. Get in touch with me on Twitter or through my website to connect!

Great article with thorough analysis. Thank you, Ms Cowan.

By examining something old with a newly popular "misogyny" lens, this observation totally misses the mark. It's really just a person alluding another person to their awkward grammar. Yes, it's a bit embarrassing to experience that on live TV especially as a burgeoning artist at the time, and Kurt Loder definitely could have handled the situation better by alluding to it in a less brusque way, but it doesn't at all feel like he was deliberately shaming her for it.

For some perspective, I've been called out numerous times on my awkward grammar, as a writer myself. Do you think that, because I also have cerebral palsy, and someone found my writing awkward or not executed very well, I'd dismiss them as being "ableist," and subsequently proceed down a rabbit hole of deriving tendencies of ableism, whether in older media or in everyday life? I could, but I'm older now. It's a waste of time to turn mild frustration into an agenda.