All That Glitters: The Star of It's a Wonderful Life Wrote a Wonderfully Unnecessary Book of Poetry

Jimmy Stewart published a volume of poetry in 1989 that leaves much to be desired. Why a successful actor might turn to poetry late in his career, and what we can learn from its existence.

You’re reading All That Glitters: (Re)appraisals of musicians, actors, and other culture-makers who have written and/or published poetry.

All That Glitters is a semi-regular feature of PopPoetry, a poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. Check out the archive to see other TV shows, movies, and films whose intersections with poetry I’ve covered. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post!

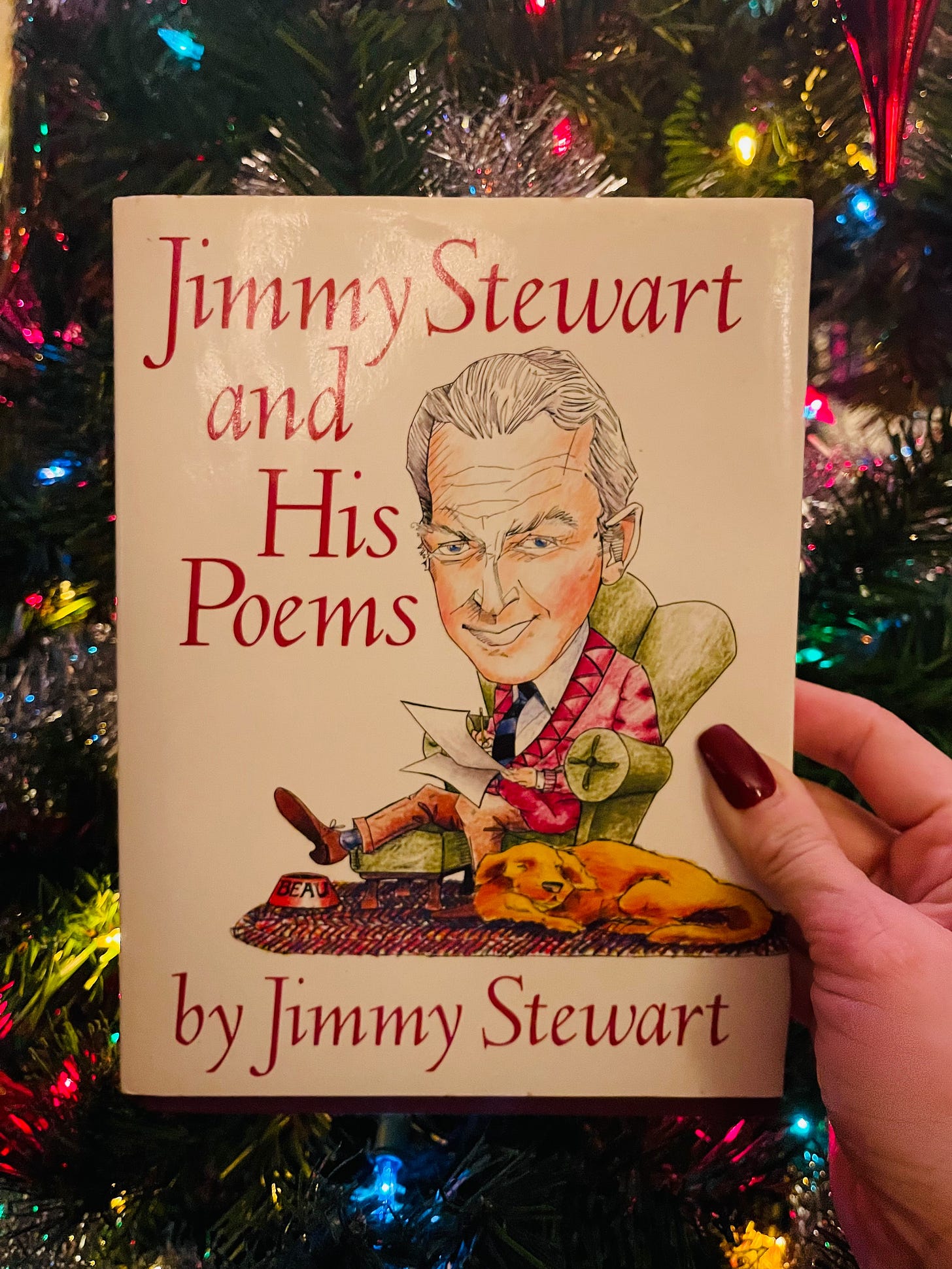

“In Jimmy Stewart and His Poems,” the book’s dust jacket reads, “the consummate Everyman shares tales from his everyday life.”

“The book confirms what we all expected—that the real Jimmy Stewart is every bit as endearing as the film characters he’s portrayed,” it continues. This promotional copy is worthy of study in and of itself: in what possible universe could one understand James Maitland Stewart, star of Vertigo, The Philadelphia Story, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life—as an “Everyman”? And, critically, why is this book of poems touted as a way to know the “real Jimmy Stewart”?

Jimmy Stewart and His Poems has a lot to teach us about what poetry can do precisely because it doesn’t do that. Marketed as a “gift,” this little book is a weird little holiday addition to my library, for all its mediocrity. Maybe it will be for the film fan in your life, too.

Jimmy Stewart…

You know this guy. Referred to as “America’s best-loved actor” on the book’s front flap, Stewart had a distinguished film career that spanned seven decades if you count his voice work in Fievel Goes West (his final film appearance) and six if you don’t. His charm and grumble and stumbling, staccato delivery along with his approachable good looks have made him a likable legend in Hollywood.

This is why watching Stewart, a titan of film, read out a poem about his dog—as he famously did on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in 1981 is—for me, shattering to his illusion as an incredible actor.

I’m only used to seeing this man being proficient at something, so watching him read an overlong poem of middling quality is downright astonishing. I’m also only used to seeing him portray emotions as opposed to actually being gripped by them. Stewart’s poetry is nakedly about himself; the notion that poetry could do anything more than serve as a vehicle for the expression of one’s selfhood doesn’t seem to be in play, here. There’s little room for anyone else’s identification or for the reader to imagine themselves at all.

If you’re wondering why and how Stewart came to poetry, you’re in luck—he tells you in the book’s prologue, or at least he tries to:

I’m sure I never said to myself, “Now Jim—why don’t you sit down and write a poem.” It’s still a mystery to me, but I think probably it’s something that happened by accident—like a lot of things that have happened in my life.

A mystery. An accident. An unknown impulse. Stewart is surely not alone in using such fuzzy terms to describe why he began writing. But it’s somehow more irritating here because, as a famous actor with a large following, he doesn’t have to have a reason for writing, be proficient, or even be interesting. If he writes a book, people will buy it.

Is it fair that people with existing followings (such as actors) are able to publish even the most pedestrian work while incredible unknown writers languish in the shadows? No. But in order to be mad about that, you’d have to argue that literary poetry has the same goals as poetry by celebrity poets, which it doesn’t. Books by famous people in other disciplines are always about peering deeper into the minds of folks we already feel that we know; literary poetry is after other goals (see the Pop Palate Cleanser for more on this topic).

After the opening passage from the prologue quoted above, Stewart goes on to tell a story about a time he was on a fishing trip in Junín de los Andes in Argentina (truly an Everyman, amirite?) and found himself consistently tripping over the top step at a hotel. He surprised himself when he later said, out of nowhere, “The top step in the hotel in Who-neen is mean.”

Stewart’s painstaking phonetic transcription of the pronunciation of “Junín” is designed to help us see that he has rhymed, and for him (and so many others), rhyming signals that one is creating or uttering poetry. It’s a complicated poetic trope because some poetry does rhyme. However, rhyming does not guarantee that one is making poetry, or rather rhyme is only one part of a successful poem.

The emotion and vulnerability Stewart showed on Carson is moving, and I would never fault him for that. He has feelings! But this is not a poem about dogs, or about loss. This, and all his poems, are about Being Jimmy Stewart.

…And His Poems

Actors and painters and poets hope to create performances, paintings, and poems that transcend their maker’s influence in some way, even if this goal is asymptotic: something they can get closer and closer to without actually achieving. Of course, many, myself included, would argue that it’s not only impossible but inadvisable to divorce works of art from the cultural and personal contexts in which they were created (looking at you, New Criticism).

The project here is not to read these poems as poems; it’s to read them as poems by Jimmy Stewart.

But folks who are already famous, like Stewart, often are more invested in setting down “their experiences” rather than creating art that can transcend their time and selfhood. The project here is not to read these poems as poems; it’s to read them as poems by Jimmy Stewart. There is no attempt by either the poet or the publisher to suggest that this work would be valuable when read in any other context.

Close your eyes and listen to the video of Stewart on Carson. Ask yourself: Are you even remotely interested in this poem if it isn’t by Jimmy Stewart?

This is not your typical volume of poetry: Stewart’s poems are each accompanied by drawings and long narrative descriptions of Stewart’s real-life inspiration. Believe it or not, there are just four poems in this volume: the aforementioned “The Top Step in the Hotel in Junín,” “The Aberdares!” (a poem about a Kenyan mountain range), “I Am a Movie Camera” (about a hyena stealing an actor’s daughters’ camera), and the famous “Beau.” Jimmy Stewart and His Poems is more of a chapbook than anything.

The poems don’t have much of a sense of argument or surprise, and focus instead on reportage, on the setting down of memories. Three of the four poems follow a stultifying ABCB rhyme scheme.

The fourth poem, “Beau,” shows a lot more variation, comparatively speaking, but is still very simple in its rhymes: some stanzas rhyme AABA, ABCC, or AABB. At moments of greater emotional intensity, the quatrains break down and the rhyme scheme hiccups and repeats:

And there were nights when I'd feel this stare And I'd wake up and he'd be sitting there And I'd reach out my hand and stroke his hair. And sometimes I'd feel him sigh and I think I know the reason why.

This is the most formal variation in the book, and it’s wonderful, after three poems of stiff ballad rhyme, to see the rhyme move along with the tone of the subject matter. I wish there were more moments like these and more attempts to break free, overall, from what Stewart thought poetry should be in order to investigate what it could be.

Overall, the poems are very general and have little to say. Too much relatability and you lose any sort of significance whatsoever. That pesky cult of relatability claims another victim.

So why write this, if you’re Jimmy Stewart: Famous Actor?

I’ve mentioned Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry before. In the first pages of that tiny volume, Lerner locates the act of writing poetry as a core need that many human beings have in order to reify their selfhood. He also notes that our core attitudes about our ability to be poets are linked to our very humanity:

We were taught at an early age that we are all poets simply by virtue of being human. Our ability to write poems is therefore in some sense the measure of our humanity. At least that’s what we were taught in Topeka: We all have feelings inside us (where are they located, exactly?); poetry is the purest expression (the way an orange expresses juice?) of this inner domain…

“You’re a poet and you don’t even know it,” Mr. X used to tell us in second grade; he would utter this irritating little refrain whenever we said something that happened to rhyme. I think the jokey cliché betrays a real belief about the universality of poetry: Some kids take piano lessons, some kids study tap dance, but we don’t say every kid is a pianist or dancer. You’re a poet, however, whether or not you know it, because to be part of a linguistic community—to be hailed as a “you” at all—is to be endowed with poetic capacity.

Poetry, he argues, seems near at hand because most of us already use language, whereas most of us don’t already use paint or pianos or tap shoes.

Lerner doesn’t state some of the more obvious here, though I will: most of us use verbal language and know how to write. The fact that writing is part of our everyday lives, even if it’s just a grocery list, moves us much closer to the realm of poetry than, say, painting, which is not a part of most of our everyday lives.

But we also get the sense that here, near the end of his life, Stewart wanted to make good on the promise of poetry to bring us into the fullest expression of our very being.

Why would an actor as accomplished and revered as Jimmy Stewart publish a deeply mediocre book of poetry?

Well, because he can. His face appears on all editions of the book, as well as in the title. Stewart had no interest in creating a book that could stand apart from his identity as Jimmy Stewart: Famous Actor.

But we also get the sense that here, near the end of his life, Stewart wanted to make good on the promise of poetry to bring us into the fullest expression of our very being—that same promise that he felt when he accidentally rhymed “Junín” with “mean.” Many people harbor ambitions to “finally write that novel” or pen a memoir, but there’s something particularly interesting about those who move into the space of poetry late in their lives. Lerner wrote in his book about letters he has received from those who are dying or incarcerated who begged him to publish their work because they “didn’t have much time.”

Writing and publishing poetry, for these folks, and for many, constituted a life goal: a mark of a life lived fully. Poetry mattered to them. It mattered to Stewart. Poetry is language dialed to 11, a shot of whiskey straight to the heart. It packs a punch and points the way right to the core of what’s important, or at least it can.

Whether or not poetry is or should be considered a core human possibility is an endlessly fascinating question, for me. I will always be interested in those who attempt this art form, famous or unknown.

Pop Palate Cleanser

Mary Freaking Oliver. You want literary poems about dogs? I give you Dog Songs, Oliver’s book about life with woman’s best friend. In the poem she reads in this video (reproduced below), Oliver achieves a kind of distillation of some of the sentiments that Stewart displays in his poem executed in an incredibly artful and literary manner.

Here’s the poem she reads:

Little Dog’s Rhapsody in the Night

He puts his cheek against mine

and makes small, expressive sounds.

And when I’m awake, or awake enoughhe turns upside down, his four paws

in the air

and his eyes dark and fervent.“Tell me you love me,” he says.

“Tell me again.”

Could there be a sweeter arrangement? Over and over

he gets to ask.

I get to tell.—MARY OLIVER

This concision, this language that is made other from everyday speech and elevated beyond the realm of the merely personal, is the best and truest example of poetry. But the elevation I’m talking about isn’t elitism, and her language here isn’t that far removed from the language we utter every day in either diction or syntax (e.g., “Tell me you love me”). It feels human and welcoming, which makes its final revelation so disarming.

Oliver’s command of the line, even in a spare poem like this one, also works to direct our attention to important units of thought rather than churning predictably toward a rhyme it reaches out for like a desperate foothold. It’s skillful and brought tears to my eyes.

Why tell you this? Because I felt for Stewart when he cried, watching that old clip on Carson. When listening to Oliver’s poem, I cried for myself, for all of us, for the animals and the humans who love them. I thought not of my long-dead dog, but my cats and how sweet our “arrangement” truly is. In short, Oliver achieved universality with her piece instead of mere relatability, which is why she was one of our greatest poets. This poetry shows us what’s possible with language, rather than merely what is.