Mary Oliver Once Asked Diana Nyad Not to Use Her Poem. Then It Ended Up on Netflix.

The recent biopic of Diana Nyad depicts her affinity for Mary Oliver, but the poet's inclusion in the movie—and the marathon swimmer's life—is more complex than you might imagine.

The Summer Day Who made the world? Who made the swan, and the black bear? Who made the grasshopper? This grasshopper, I mean— the one who has flung herself out of the grass, the one who is eating sugar out of my hand, who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down— who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes. Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face. Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away. I don't know exactly what a prayer is. I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass, how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields, which is what I have been doing all day. Tell me, what else should I have done? Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon? Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life? —Mary Oliver

If you just read this poem for the first time, I envy you. Mary Oliver’s “The Summer Day” is a masterpiece, deeply characteristic of Oliver’s favorite subject matter—the natural world—and her holy reverence for life on earth.

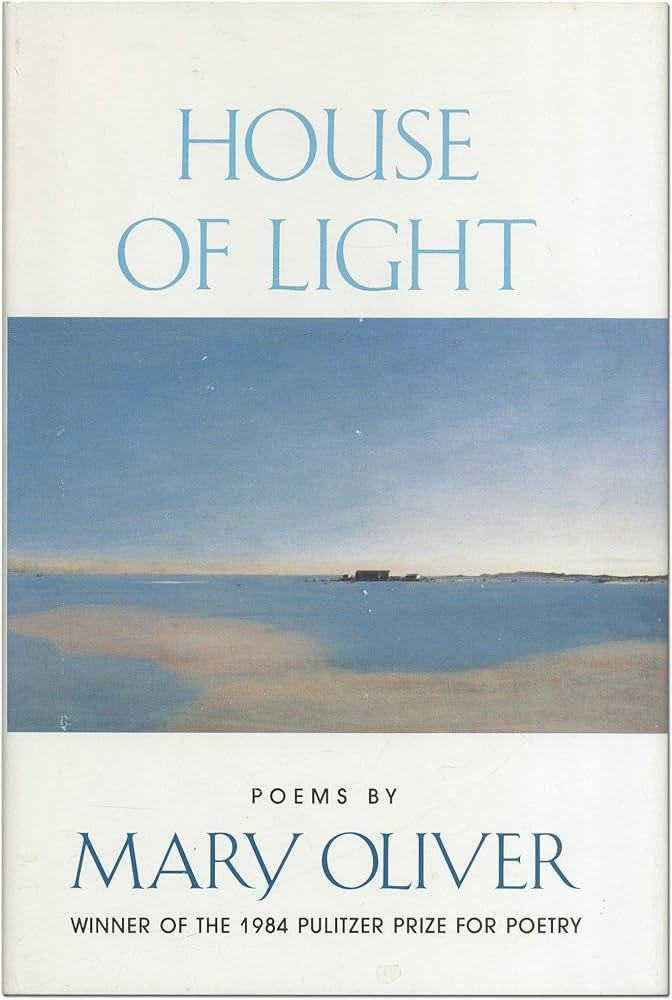

Included in her 1990 book House of Light, the poem and its famous final couplet feature prominently in a recent film featuring Annette Benning as marathon swimmer Diana Nyad, a dynamic figure whose ego and accomplishments are forever struggling to outstrip one another.

Nyad has claimed to swim around the island of Manhattan, from the Bahamas to Florida, and, famously, from Cuba to Florida, though official certifying bodies have declined to ratify many of her endeavors. She has often embellished or, as the LA Times terms it, exaggerated her accomplishments.

Nyad is rounded out by an as-always impeccable Jodi Foster as Bonnie Stoll, Nyad’s longtime friend and coach, and Rhys Ifans as John Bartlett, Nyad’s cantankerous ocean navigator. Oliver and her work are so important to Nyad that you might even consider her to be a supporting character herself.

But several mysterious and even painful details surround this poem and its place in Nyad’s life and the 2023 film based on the swimmer. Wild, indeed.

Oliver on Screen… or Is She?

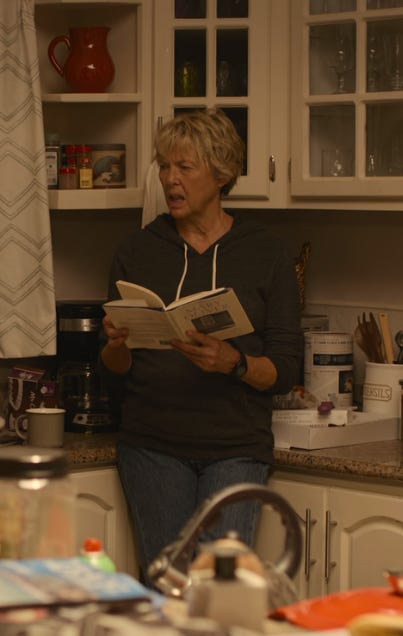

Before the main title of Nyad even appears, Diana asks Bonnie to listen to a bit of a poem. She reads the ending of “The Summer’s Day” from what’s supposed to be an old dog-eared copy of a book her mother died with at her nursing home. She first mused that her mother might have left it as a breadcrumb for her to find but later found out that the book was owned by someone else at the home, not her mother, who was, as Diana calls it, “a pushover.” Deflated, she continues to read the book anyhow.

Standard fare, right? Not quite.

The book is a hardcover with a dust jacket, and in the bathroom scene, you can see that it is titled House of Light, the book where that poem first appeared. The cover shows a small image box in the center of the design that appears to have a photograph or painting of a window.

However, I can find no evidence that an edition of the book with this cover exists.

Crucially, the real book’s title appears above the image, not the poet’s name. The cover of House of Light also shows a full-width landscape, not a centered image of a window, in both the paperback and hardback editions. What’s up with this?

The book Annette Benning is holding in these scenes looks a great deal like Devotions, Oliver’s 2020 collection of selected poems. Devotions is more readily available, to be sure, but is some 480 pages long and therefore too thick to pass for a slim earlier-career collection.

Am I overthinking this? Do I need a hobby? Oh shit… this is my hobby. Whoo!

The producers certainly shouldn’t have had trouble locating the book: a used copy of the hardcover can be had online for about $9 as of this writing. Were they too lazy to track it down? Did they doctor the dustjacket of Devotions to make it seem like Benning was reading from the 1990 collection instead? Why do producers do this? That’s way more work than just sending a PA on an internet sleuthing mission to find the real book.

Later in the film, Bonnie hears Mary Oliver reading “The Summer Day” on the radio and takes it as a sign that she should return to Diana’s side as she mounts a fifth attempt to swim from Cuba to Florida in her mid-60s. The audio of Oliver reading the poem sounds a bit like this reading of the poem that was captured on the CD recording At Blackwater Pond and refers to this 2012 NPR interview, though I wasn’t able to source the exact radio broadcast itself (the host refers to “public radio” but not “NPR,” which suggests that it’s an audio file explicitly collaged for the film). This feels like a smaller echo of the book scene: correct in broad strokes but fuzzy on the details.

Did Oliver’s estate ask the producers not to include the actual book in the film? It’s not unthinkable, especially because Oliver denied Nyad an opportunity to more closely associate herself with her poetry while she was alive.

Nyad’s History with Mary Oliver

“The Summer Day” might be termed Nyad’s favorite poem. She has spoken of it often, and as of this writing, Oliver’s line still serves as a kind of slogan on the landing page of Nyad’s website. The swimmer also posted a tribute on Facebook when Oliver passed in 2019.

Daniel Slosberg, a former marathon swimmer who once met Nyad for three minutes in 1980 and has made “fact-checking” Diana Nyad his passion, took offense to that.

Any poking around you do about Nyad online will turn up his obsessively detailed and frequently updated site. So deep and detailed is this man’s dedication to “exposing” Nyad’s purported falsehoods that the only rational response to his intense platforming is get a life. It’s… a lot.

I know that athletics are at least in part about precision and stats and numbers. But the poet in me feels a massive eyeroll coming on. Oh wait, it’s happening. Hang on…

What I mean is that Diana Nyad, a woman who has swam great distances in open waters, done motivational speaking, written books, and inspired countless people, has certainly accomplished a great deal, even if she hasn’t played by the rules. One wonders if a woman would mount such a campaign to discredit a boastful male athlete, but I digress.

But Slosberg is sadly correct when he notes that Oliver asked Nyad not to use the words from her poem as a subtitle to her 2015 memoir, Find a Way, which she envisioned as Find a Way: A Wild and Precious Life. He sources this fact with Nyad’s own words from a 2019 interview.

However, where Slosberg takes this to mean that Oliver did not want to be associated with Nyad because of her character, it likely has to do not only with Oliver’s desire to retain her association with her own work but also with the way Nyad interprets the poem itself.

Oliver and Astonishment, or What Nyad Gets Wrong

I have not fully solved the mystery of the film prop book used in Nyad. But what I do know is that the swimmer’s relationship with the poet was not straightforward. So ferocious was Nyad’s passion for Oliver’s poem that she became obsessed with it, and tried to make it a part of her own legacy by thundering it from stages during speaking engagements, even if she did credit Oliver as their creator.

And so it is possible that Oliver’s estate did not grant permission for the use of the book. But the real crime has to do with the way that Nyad and Nyad interpret the poet’s words.

Oliver’s requirement that the poem not be used in the film’s subtitle, particularly as “A” Wild and Precious Life, was spot-on. To do so would have subtly suggested that some lives are wild and precious and others are not, and it also would have telegraphed a critical misunderstanding of her work.

Though Nyad’s accomplishments are impressive no matter what you think of her official record, seeking to set an athletic record or be the “first” to do something or to swim a long distance is not exactly the kind of result Oliver’s poem seeks in its exhortation.

For the love of god, the poem says in between its lines, there are other good things beyond mere success: love, kindness, and wonder, to name a few. Stillness. Watching a grasshopper clean her face.

In a time when we’re redefining what it means to live a good life and turning a critical eye on “hustle” culture, it’s important to point out that Oliver’s poem—and her oeuvre more generally—isn’t asking us to achieve more; it’s asking us to be more present. “The Summer Day” asks us to slow down. To notice. To immerse ourselves deeply in the natural world and to delight in the wonder of simply being here.

This urging is mirrored in another oft-quoted poem of Oliver’s called “Sometimes,” from her 2008 collection, Red Bird:

Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.

All lives are both wild and precious. Oliver’s poem asks us to wake up to that fact and come alive to the astonishment we can feel while we’re still here on earth. Mary Oliver would likely consider a few days aimlessly wandering forest trails listening to chickadees and looking at hemlock trees just as worthwhile of an endeavor as swimming from Cuba to Florida. Honest to god. We are too prone to believe that accomplishment equates to happiness. For the love of god, the poem says in between its lines, there are other good things beyond mere success: love, kindness, and wonder, to name a few. Stillness. Watching a grasshopper clean her face.

It's true that Nyad no doubt did her share of noticing—how could she not?—while spending countless hours in the ocean: the salt and jelly stings, the slap of waves and the blinding cold. All of it. But the film’s positioning of the poem as an impetus for Nyad to achieve her lifelong dream of swimming from Cuba to Florida is too easy, too sports-film-y, and denies the complexity of Oliver’s work and, it has to be said, the complexity of what it means to live a life: wild, precious, or otherwise.

Related

Read Mary Oliver’s “Little Dog’s Rhapsody in the Night” in the postscript to this entry on Jimmy Stewart’s book of poems:

All That Glitters: The Star of It's a Wonderful Life Wrote a Wonderfully Unnecessary Book of Poetry

·You’re reading All That Glitters: (Re)appraisals of musicians, actors, and other culture-makers who have written and/or published poetry. All That Glitters is a semi-regular feature of PopPoetry, a poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it

Check out other biopics I’ve covered in the archive:

Ahh, this is so good! It reminds me of my own pet peeve topic, how everyone misinterprets the quote "Well-behaved women seldom make history."

This might be one of my favorite posts you've ever done, in part because I LOVE the sleuthing around the book prop. That is the kind of shit I can really go down a rabbit hole about, and I love that you did here! And I love that poem (who doesn't?) and can totally see how it perverts its meaning to apply it to a life that is meant on film to be special and big in a way that the poem does not prioritize.