Christmas Bells & Christian Feeling: Longfellow Gets the Hallmark Treatment

The Fireside poet is the center of the first film from a company known for its live-action religious stage shows. The result? Surprisingly thoughtful about poetry, but clumsy regarding his religion.

A Christmas movie about a poet: what a welcome entry into the canon! Right? Right?!

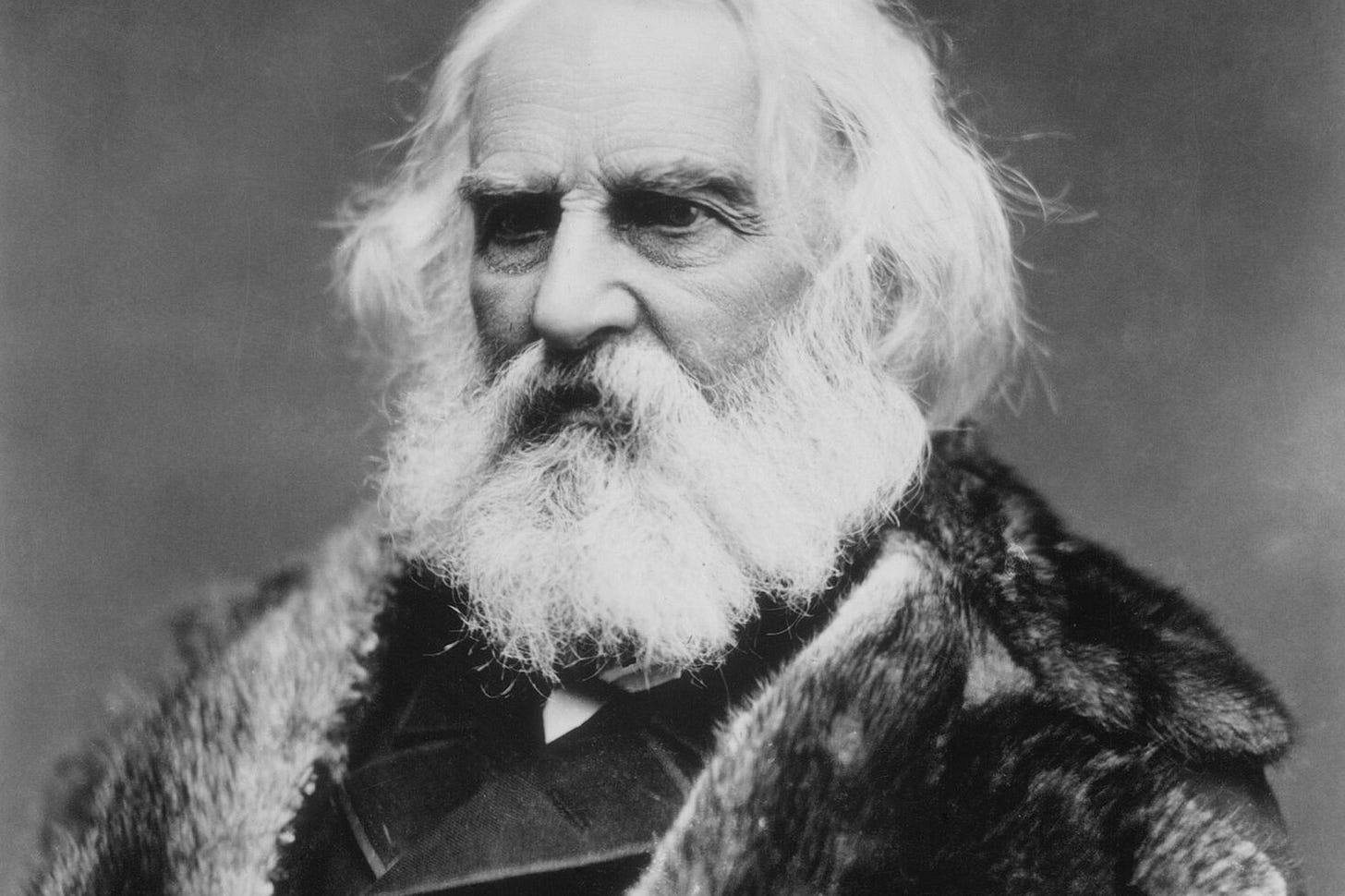

I Heard the Bells is a 2022 holiday-themed film about the mid- and later life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. But the filmmakers have purposefully amplified what may have been only a low hum in the poet’s life: religion.

The film is indeed “based on a true story,” as it reports in the opening title card. It follows the historical details of the poet’s life fairly well, but it only guesses, as biographies must do, about the interiority of the poet’s mind and heart as well as the degree of his own religiosity.

Longfellow & God

I Heard the Bells is a Christian film made by Sight & Sound films: the company’s first such endeavor. Known for their live-action religious entertainment events, Sight & Sound seeks to “tell true stories about historical figures whose lives changed the world because Christ first changed them.” The film casts Longfellow as a deeply religious, devoutly church-going man who has an actual confrontation with the divine near the film’s end. In life, things were more complicated, as they usually are. The extent to which “Christ… changed” Longfellow is subject to a good deal of interpretation.

In “Literary Friends and Acquaintance; a Personal Retrospect of American Authorship” (1901), author and critic William Dean Howells said of Longfellow, “I think that as he grew older his hold upon anything like a creed weakened, though he remained of the Unitarian philosophy concerning Christ. He did not latterly go to church.”

Borrowing Flannery O’Connor’s description of the American South, Catholic writer Charles A. Coulombe described Longfellow as “Christ-haunted,” which might be the most apt way to think of the poet’s relationship with religion. He was fascinated by it and wrestled with it. With a life like his, who could blame him?

Longfellow knew despair intimately: His first wife died in the aftermath of a miscarriage, and his second wife and mother to his six children died in a freak fire. Longfellow was badly burned trying to save Fanny and sank into a deep depression. His son enlisted in the military during the Civil War two years later against the family’s wishes and was severely wounded.

Who wouldn’t turn to God in such situations? It’s clear, however, that Longfellow also placed something else at the center of his belief system as well.

Longfellow & Poetry

Longfellow achieved a rare feat, like Byron before him across the ocean: he was well-known in his time. In the film we see Longfellow being referred to as the “nation’s prophet” right in front of him. Can you imagine?

Longfellow takes his public poet duties seriously. “We need poets to change the world, Henry… not politicians,” he’s told in one scene which echoes Shelley’s well-known sentiment about the role the poets could or should play in society. He responds again and again to the palpable desire in the society of his time for poets to corroborate or clarify feeling and national sentiment. With the Civil War at first looming and then in full bloom, this has significant ramifications for the country—who knows Longfellow and reads him eagerly—as well as for Longfellow himself and his family.

All poetry is political, right? We get the sense that Longfellow both does and does not agree with this. Later in the film, Longfellow grapples with his identity as a public poet, feeling as if he can’t possibly speak to the tragedies unfolding in the country when he is unable to write cogently about his own personal tragedies.

In a moment of frustration, Longfellow’s son Charles huffs, “This is not a poem. I am not a poem.” I laughed. Is this what my daughter will tell me one day as I try to use my poet-knowledge to soothe and guide her? Probably. So few films are focuses solely on poetry that it feels bizarre to see exchanges like this one on screen.

He’s suggesting that the poet, or that writer more generally, is capable of an almost-Godlike power by which they are able to make the ephemeral eternal.

The film is highly watchable and beautifully made in most respects. But in such a sumptuously set and costumed film, one detail repeatedly jarred me and took me out of the narrative time and again: the wigs. The wigs! And really, just Longfellow’s wigs. Oh, goodness. The fluffy, pasted-on mutton chops! The shiny, synthetic black mop! I’ve truly seen better quality wigs for sale at Spirit Halloween. Why fall down at the finish line with the makeup and character design for the film’s famously hirsute Fireside poet protagonist? But I digress.

Longfellow asks the film’s primary surface question out loud in different iterations: how can love and poetry and, yes, God, exist in a world where my wives keep dying terrible deaths, my son is severely wounded in a battle I basically drove him toward, and slavery dehumanizes Black people and stains the nation?

But the deeper questions have to do with what a poet’s role is in society, what their obligation is in times of trouble, and what it means to be “eternal.” This last point is the fulcrum on which the film’s final act pivots, and its conclusions are simplified in a way that isn’t satisfying.

Poetry & God

The film dramatizes a moment in Longfellow’s life, where he ostensibly has an encounter with God. This moment is directly precipitated by a discussion about poetry and the power of the written word.

Distraught with grief, over the death of his wife Fanny, Longfellow goes to his church and speaks with a reverend. In so many words, he asked the pastor how God can exist when terrible things happen in the world. It’s the age-old question. When Longfellow tells the reverend about his spiritual questioning in the wake of his grief for Fanny, the reverend points out that Longfellow’s wife has passed from her earthly life, she is eternal in Longfellow’s poetry.

The Reverend’s answer is interesting and unusual. He says that just as God continues to speak to us through the words of the Bible, Longfellow’s wife continues to speak to him, and will always speak to him through Longfellow’s own writing about her. In a sense, he’s giving a bit of God’s power to Longfellow: he’s suggesting that the poet, or that writer more generally, is capable of an almost-Godlike power by which they are able to make the ephemeral eternal.

Heartened by this, Longfellow rushes from the church back home to write for the first time in ages. The film goes to great pains to show him sweeping the cobwebs off his writing desk. There, he finds traces of his late wife that he has never seen before: a letter she asked him to post on the day she died that has gone unmailed, a sketch she did of him dozing by the fire. He takes this as evidence of God rather than evidence of his wife, the past, her love for him, or anything else. He begins to write the poem we now know as “Christmas Bells.” This scene is extremely arresting: it shows Longfellow torturing himself while drafting the poem late into the night. For a moment, you believe that he’s going to land on a very poetic realization:

And in despair I bowed my head; "There is no peace on earth," I said; "For hate is strong, And mocks the song Of peace on earth, good-will to men!"

But that’s only the penultimate stanza. And because this is a religious film, and because Longfellow is who he was—a fireside poet who, as the character says in so many words during the film, wishes for his poetry to be a balm, not a sword—turns the poem around in its final stanza:

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep: "God is not dead, nor doth He sleep; The Wrong shall fail, The Right prevail, With peace on earth, good-will to men."

In 1977 Ann Douglas, Parr Professor Emerita of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, penned this incredibly spicy estimation of Longfellow’s contribution to poetry: “goody two-shoes kind of literature ... slipshod, sentimental stories told in the style of the nursery, beginning in nothing and ending in nothing.”

It may be that Longfellow fell out of fashion because of his desire to bring things square, to tidy and simplify them rather than highlight their nuance and complexity. It may be because America and her reading public simply grew up, or stopped reading poetry so broadly.

Longfellow is perhaps most interesting today in his role as a “famous” public poet of the 19th century, even if the poems he left behind don’t grip us as they once did. Historical evidence bears this out, but is much less sure about the poet’s deep faith in god, which makes the decision to make a Christian film about him even more perplexing.

I Heard the Bells is a warm and fuzzy Christmas movie that many poets might enjoy watching once or even annually. But it seems as if the filmmakers read “Christmas Bells” and decided who the poet who wrote it must have been before actually delving into his work, his reputation, and the man himself.