I'll Be Home for Christmas Serves Up E. E. Cummings & Poetry Stereotypes in a Literal One-Horse Open Sleigh

Not Even the Corn Has Such Big Ears

It’s almost 2021 (thank god) and I’ve got one more holiday treat for you before the ball drops. A friend invited me to a Zoom Present-a-Thon for her birthday recently, and it was very excellent. Each participant was tasked with creating a PowerPoint presentation on a topic of limited seriousness for no more than five minutes. There were impassioned defenses of Avril Lavigne’s “Hello Kitty,” step-by-step guides for how to honeypot Elon Musk, and rankings of the, uh, let’s say dateability of various wizards. Cat sound.

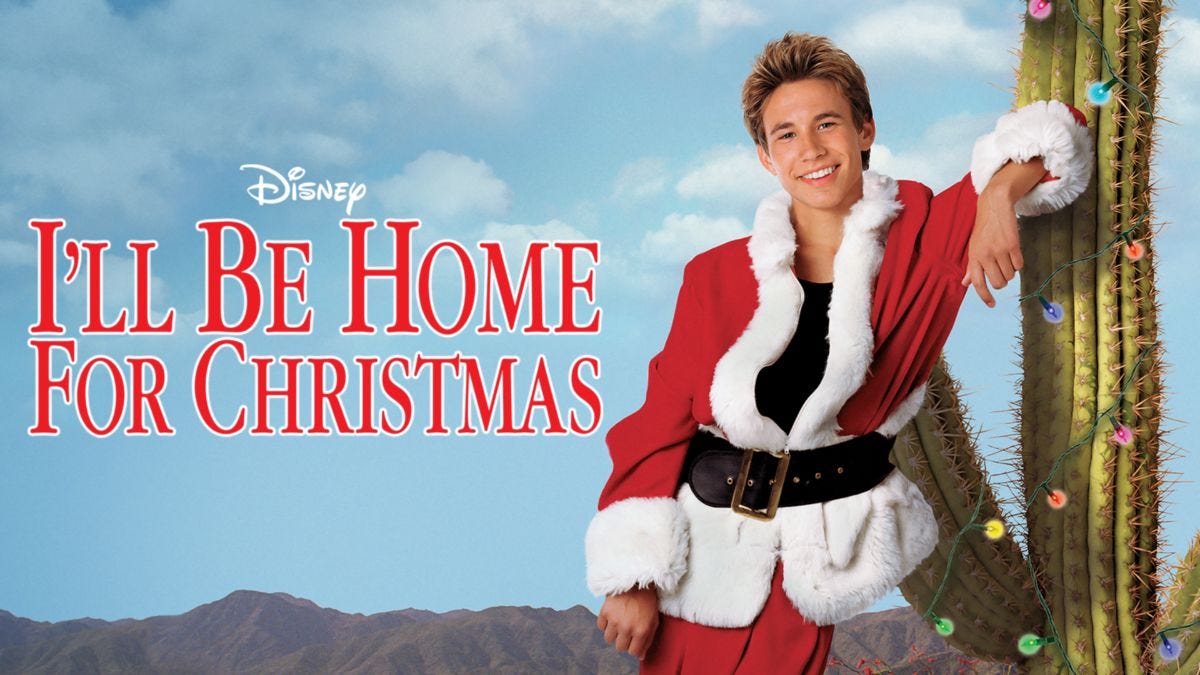

My presentation involved holiday movies and, you guessed it, poetry & popular culture. I had such a good time making the slides and relishing all 86 minutes of a particularly baffling Disney holiday movie’s late 90s aesthetics that I thought I’d expand on it here to send 2020 off in style: by ripping into a movie that, while it may have (re-)introduced some to the work of E. E. Cummings, dabbled in some of the basest and silliest tropes about poetry and its readers.

To quote Jonathan Taylor Thomas at 00:16:26, “This is not acceptable!”

Some Background

The 1998 box office bomb I’ll Be Home for Christmas, starring JTT of Home Improvement fame (and, I guess, more recently, Last Man Standing fame… do you think he’s invited to Tim Allen’s house for Christmas dinner?), is certified shitty on just about every aggregator out there. Roger Ebert once called this movie “an exercise in cinematic Ovaltine.” Talk about poetry! It’s currently streaming on Disney+ for:

Millennials hoping to recapture the magic of their childhood Christmases

PopPoetry readers who want to hear Jessica Biel call JTT “a genuine butthole” in a very serious and climactic scene

I’ll Be Home for Christmas debuted the same year JTT left Home Improvement to “focus on academics.” What a world it would have been if the movie’s writers had focused a bit more on the poem that gets top billing in a critical scene between two potential love interests.

First, an ultra-quick overview for the uninitiated: Through a series of shenanigans, Jake (Jonathan Taylor Thomas) wakes up in a California desert glued into a Santa suit and has to make it home for Christmas dinner in New York or else forfeit his dad’s Porsche 356. He was supposed to drive home with his girlfriend Allie (Jessica Biel), but when he doesn’t show because of the aforementioned shenanigans, she opts instead to drive home with Eddie (Adam LaVorgna), an annoying rival for her affections.

A great little case study on poetry’s place in popular culture in 1998 and beyond, I’ll Be Home for Christmas is nearly unwatchable, and that’s coming from someone who loves Christmas movies. But I haven’t been able to stop thinking about one of the key scenes from the movie in which a character quotes E. E. Cummings. But before we get to the scene, let’s talk tropes.

Poetry & Pop Culture: Some Tropes

Below is a woefully incomplete but accurate list of common tropes, stereotypes, and tired telegraphs of poetry’s place in the world. These felt even more cemented 22 years ago when I’ll Be Home… premiered, and I would argue that things are changing now in the year of our lord almost-2021, albeit glacially. Try these on for size and think of all the ways you may have seen them justified in media, in real life, or in the ether, if you’re prone to spending time there:

Poetry is for nerds (and women).

Poetry’s status as a highfalutin art form is well-documented, and I talk about it a lot on PopPoetry. Though the idea that one needs an advanced English degree to enjoy poetry persists today, this stands in stark contrast to poetry’s humbler beginnings as a form of oral storytelling that could be enjoyed by anyone. Poetry is older than literacy itself, after all. But because it has receded from the center of public life and popular culture, engaging with it is as nerdy as building ships in jars or playing chess (though a new Netflix series threatens to upset that notion!) Poetry also suffers from the contemporary notion that it is not for “real” men, despite the fact that historically it was written, published, and reviewed exclusively by men. I’m feeling a little gaslit, so let’s forge ahead…

Can you name any poet? You are now a nerd. Congratulations.

A seeming contradiction in terms from Trope 1, any knowledge of poetry equates to a total knowledge of poetry or renders one the “type” of person who reads poetry. You would think that nerdery requires extensive knowledge of a particular subject or fandom, but when it comes to poetry in popular culture, a kind of one-poet or one-poem rule seems to be in effect. What else is like this? Opera? Certainly not sports: it’s well-documented that attending a single sports game proves nothing about one’s general sportsball proclivities. A little knowledge, apparently, is a dangerous thing.

Poetry is meaningful and deep because it is difficult to understand.

This is one of the most tenacious stereotypes about poetry, and its consequences are far-reaching. The idea that poetry’s magic lies in its ability to conceal its meaning and present the reader with difficulty for the sake of being difficult is pervasive among readers of all levels. I’m happy to lay the blame at the feet of the canon of dead white men whose elaborate, soporific verse tends to make high-schoolers hostile to the very idea of poetry. My longtime contention is that we should raise folks on more lucid, more contemporary stuff by diverse, living writers before even thinking about asking them to engage with Tennyson. Poetry can be multilayered and deep without making its readers feel like they are stupid or poorly read or not being addressed for who they are.

All poetry is romantic and reciting it gives one clothes-removing power.

For many, this one has some truth to it. Poetry can be intensely romantic, erotic, and powerful. Though it’s not the only thing poetry can do, romance is the only function poetry serves in the movie under study.

How I’ll Be Home for Christmas Engages Poetry Tropes

Before Disney takes down the video I clipped above (fingers crossed), watch it. Then, let’s revisit our list:

Poetry is for nerds (and women).

Allie is impressed by Jake’s recitation of the Cummings line, but Eddie is not. Though he fancies himself a modern, enlightened guy (hoo boy) Eddie can’t understand why the recitation of a line of poetry would give Allie “chills.” Part of this just seems like Eddie is dense, non-boyfriend material, but part of it is also definitely related to this trope, which states that masculine hetero dudes apparently have to hate poetry because (at least in 1998, and still today, if we’re being honest, though perhaps to a lesser extent) feeling feelings makes you less of a man.

Can you name any poet? You are now a nerd. And possibly a woman. Congratulations.

For me, a kind of poetry “insider” trying to de-inside poetry for everyone else, choosing Cummings as the poet that Jake quotes is really first-thought and sophomoric, for me. And don’t get me wrong! I love Cummings. I studied him extensively in college and beyond, and I loved teaching him. But Cummings has a lot of name recognition for an avant-garde poet who made punctuation and syntax his personal punching bags. You’ve heard of this guy, even if you haven’t read him. I can’t even figure out what a more obvious choice would have been. Shakespeare? Nonetheless, a Bustle writer once boldly claimed that IBHfC was “one of the smartest movies Disney has ever made,” and cited the inclusion of the Cummings poem as evidence, thus solidifying my point. The nerd woman in the movie liked it, and so did the nerd woman who writes for Bustle. I rest my case (*sobs in poet*).

Poetry is meaningful and deep because it is difficult to understand.

Eddie does not understand the line Allie quotes and makes fun of it by mimicking its syntax to create an insulting joke (who doesn’t love to hear about their big ears?) before launching into a limerick. Which reminds me…

Trope 3b: Limericks are the best and only worthwhile form of poetry for hetero everymen like Eddie.

I will have to launch a more exhaustive investigation into the limerick in popular culture, but anecdotally I can tell you that when I tell a man that I’m a poet, it results in their recitation of a limerick—sometimes even one that they’ve made up—about 75% of the time.

And last but not least…

All poetry is romantic and reciting it gives one clothes-removing power.

This one is going to take a little more time to dig into…

Here’s the Cummings poem that Allie quotes from in its entirety:

somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond

somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond

any experience,your eyes have their silence:

in your most frail gesture are things which enclose me,

or which i cannot touch because they are too nearyour slightest look easily will unclose me

though i have closed myself as fingers,

you open always petal by petal myself as Spring opens

(touching skilfully,mysteriously)her first roseor if your wish be to close me,i and

my life will shut very beautifully,suddenly,

as when the heart of this flower imagines

the snow carefully everywhere descending;nothing which we are to perceive in this world equals

the power of your intense fragility:whose texture

compels me with the colour of its countries,

rendering death and forever with each breathing(i do not know what it is about you that closes

and opens;only something in me understands

the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses)

nobody,not even the rain,has such small hands

JTT, in his infinite wisdom, quotes the very last line of the poem (or so we’re told! The story of his recitation is secondhand) to Jessica Biel when she’s having a “down day.” This makes her starry-eyed and informs her decision to continue dating him even though he seems to be, for all intents and purposes, a major tool. The line she quotes is, perhaps, a bit more well-known if one knows the poem it comes from or knows Cummings at all. But it’s confusing: without the full context of the poem and its intricate metaphor of flower and rain, of the poet’s musing about how powerful the rain can be while still remaining delicate, it sounds kind of strange.

Picture your Tinder date turning to you at the end of the night and saying “nobody,not even the rain,has such small hands.” I’m pretty sure it would feel like grounds for sending that emergency text to your best friend.

The penultimate line of the poem would have been a steamy choice: “the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses).” That certainly has the power to melt even the frostiest of your 90s Rom-Com queens, but it’s still a little strange in the same way that the final line is strange. Cummings’ descriptive synaesthesia is on full display, here. Voice, which we perceive with our ears, is attributed to the eyes. Furthermore, “deeper” pulls double duty as a word that can mean sonically low (like a baritone or bass voice) or visually and physically cavernous (like a well or a crater). It takes a little more thought to even attempt an understanding.

For my money, I would have had JTT offer Jessica Biel line 5: “your slightest look easily will unclose me.” It survives apart from its context. The only true strangeness here is Cummings’ invention of a new word, “unclose,” whose meaning can be easily guessed. You wreck me. You undo me. That’s hot.

But even with these sexier lines available, the writers went with the poem’s final line in the movie: the weird line, the inscrutable line, a line that preserves the lie about poetry’s inaccessibility, its niche status, its too-rich-for-my-blood frisson of WTF.

It might be that this was simply the writer’s favorite line. Or he threw a dart at the poetry shelf in a Borders bookstore (it was the late 90s, after all). In either case, we’re not always aware of our biases, our automatics. Stereotypes persist because there is sometimes a grain of truth to be had within them: empirically speaking, that line is weird as hell! I mean… look at it! Not even the rain has such small hands? Put yourself in Eddie’s position: he considers himself to be a “Millenial type of guy” who “dig[s] world music” (typing that caused me physical pain) but come on! Rain doesn’t have hands, dude!

In a weird and fascinating moment, after hearing the line of Cummings poetry, Eddie grabs Allie’s ear and intones, “Not even the corn had such big ears.” I’ve watched the scene more times than I care to recount at this point, and I still can’t tell whether we’re supposed to interpret Eddie’s manipulation of Cummings’ syntax into a joke about Allie’s ears as a serious attempt to create erotic poetry or a flat-out attempt to denigrate poetry’s value (and Jake’s). When Allie bristles and laughs, he says, “Look, if it’s poetry you want, baby, I got it.” What he offers next is the beginning of a well-known limerick, a poetic form whose structure hinges on a joke or reversal, and often a crude one.

It’s almost as if he can’t bear the tenderness that the line of poetry offers. That, then, is the scene’s sole success when it comes to depicting poetry. One of poetry’s most important jobs is to help us look clearly at things we don’t want to see. If, for this character, and maybe for young men of the 90s, that thing is intimacy, then Cummings’ poem, even one line—one poorly chosen and expertly written line—is the beginning of a balm. Maybe that’s the work of poetry when it comes to popular culture, winning over the Allies and Eddies of the world one line at a time.

If you do decide to stream I’ll Be Home for Christmas this season or next, do yourself a favor and take a piece of advice from Cummings himself regarding one of his more difficult plays:" “DON’T TRY TO UNDERSTAND IT, LET IT TRY TO UNDERSTAND YOU.”

You know, 2020 was tough. In 2021, I hope to bring you PopPoetry posts even more regularly, and I hope to showcase guest posts and threads, too! If you liked what you read today, please share and subscribe! It means the world. Happy reading, happy watching, and a Happy, Happy New Year to you all!