Heartstopper Highlights the Internet's Favorite Book of Poetry

An asexual, aromantic TV character reads a book about obsession and gay identity. Among the many who noticed was the book's author, well-known to fandom communities and literary types alike.

Earlier this month, poet Richard Siken posted a Netflix screenshot to a social media feed with a kind of measured bemusement. He merely states the facts: “There’s a show on Netflix called Heartstoppers. On a recent episode, Issac is reading Crush at a party.” But the subtext, I think, is “OMG.”

At least that was my reaction. Yes, the intersection of poetry and pop culture is sort of my whole thing, but there’s something extra thrilling about seeing the work of living poets featured in zeitgeist-y pop culture. Better still? The poet themselves finding out about it and reacting to it.

Siken’s post has more than 10,000 likes. Fans of the show and of his poetry chimed in to offer their congratulations and support. Some called the book’s star turn “a big win for sad gays everywhere” or noted that reading Crush is a “formative part of the modern queer experience.” Many of Siken’s fans are what some call “very online”: Siken’s poetry is popular in fandom communities, and enterprising Google searchers can find various image threads interspersed with film stills, drawings, and other visual ephemera in order to create alternative storylines on sites like Tumblr.

Siken is not only aware of this phenomenon but has written about it more than once and even made charming, self-deprecating jokes about it. It’s very rare for a poet to occupy this particular space, and now his work is being highlighted in yet another corner of the pop culture universe.

What is this adored book? Why does it inspire this kind of usage and response? And why is it on this show?

you’re the star, / so smile for the camera

Based on Alice Oseman’s bestselling graphic novel series, Heartstopper follows a group of young friends as they navigate queer relationships and friendship in the UK. The show has done very well, becoming one of the platform’s most-watched shows upon release.

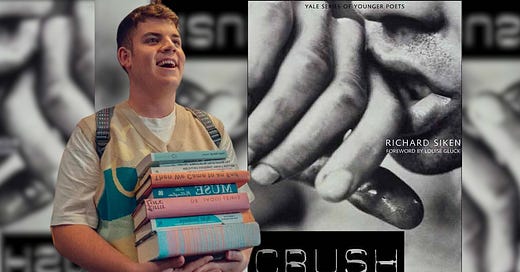

Isaac Henderson (Tobie Donovan) is a character invented whole-cloth for the show who does not appear in the graphic novel series. Known for his love of reading, Isaac always has a book nearby. When the group travels to Paris and visits the famous Shakespeare & Company bookstore, Isaac is seen adding yet another book to a precariously tall stack he intends to purchase. Numerous sites have compiled detailed lists of every book Isaac has read in each season of the show. Isaac’s reading list is excellent, and spans various genres, eras, and themes, though most have to do with queer identity in some way.

In Season 2 Episode 6, “Truth/Dare,” Isaac can be seen reading a copy of Richard Siken’s Crush. Selected by Louise Glück for the 2004 Yale Series of Younger Poets competition, the book is remarkable in many ways, not least of which is that it has developed a cult following online among more general readers and was also lauded in the literary community.

Isaac is first shown reading the book in a hallway outside a party. James sits down next to him and tells him he has a crush on someone (spoiler alert: it’s him). They kiss, but sparks do not fly. The crush is one-sided. Isaac is canonically an aromantic asexual character, according to Oseman.

Isaac prefers to read about love and sex but doesn’t wish to personally experience either, which is all well and good except for the fact that he doesn’t have a community around him that feels the same way.

Later, Isaac is still reading the book but actually at the party, and during a game of Truth or Dare to boot. Big ups, my man. If only more people brought poetry books to parties, amirite? (If Siken’s comment thread is to be believed, apparently they do). The conversation turns to celebrity crushes while Isaac is still holding Crush. Celebrity crushes are always one-sided (unless you’re Hailey Bieber, I guess). Isaac continues to come close to the orbit of a crush without actually experiencing it for himself.

The third time we see Isaac reading the book it appears that he’s just finished it—it’s lying next to him on a confetti-covered balcony in the party’s aftermath. He has headphones in and is alone, staring out at the streets of Paris. In this moment, another meaning of the book’s title begins to blink into wakefulness: something about his post-party loneliness seems a bit flattened, ground down. The real-life infatuations of his classmates aren’t of interest to him. Isaac prefers to read about love and sex but doesn’t wish to personally experience either, which is all well and good except for the fact that he doesn’t have a community around him that feels the same way.

This stands in such contrast to the kind of crush or crushing energy of Siken’s book, which is deeply rooted in physical, sexual relationships and romantic love or its lack. While visibility for various queer identities has increased, asexuality and aromanticism have lagged behind, remaining less understood and accepted. In online communities, Isaac is a favorite precisely because so little representation for aroace people exists in popular culture.

Siken’s book has continued to reach new audiences of young queer people in the two decades after its release, first through internet fandom communities centered on pop culture and now through a bonafide piece of pop culture itself.

Why this book?

Every morning the same big / and little words all spelling out desire

Crush is hypnotic, breathless. Achingly precise in its image-making and narrative spinning, Crush has mainly to do, according to Glück, with “panic.” In one of the most iconic and knock-down fabulous introductions of all time, Glück described Crush this way:

Crush is the best example I can presently give of profound wildness that is also completely intelligible. By Higginson’s report, Emily Dickinson famously remarked, “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that it is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that it is poetry...”

She should, in that remark, have shamed forever the facile, the decorative, the easily consoling, the tame. She names, after all, responses that suggest violent transformation, the overturning of complacency by peril.

In practice, this has meant that poets quote Dickinson and proceed to write poems from which will and caution and hunger to accommodate present taste have drained all authenticity and unnerving originality. Richard Siken, with the best poets of his impressive generation, has chosen to take Dickinson at her word. I had her reaction.

No wonder this book has reached and meant so much to so many.

What are Siken’s poems actually like? I urge you to seek out his work for yourself and have the top-of-your-head-removing experience Glück describes, but here is a taste. Consider this excerpt from “Litany in Which Certain Things Are Crossed Out,” a poem that appears in Crush:

The entire history of human desire takes about seventy minutes to tell. Unfortunately, we don’t have that kind of time. Forget the dragon, leave the gun on the table, this has nothing to do with happiness. Let’s jump ahead to the moment of epiphany, in gold light, as the camera pans to where the action is, lakeside and backlit, and it all falls into frame, close enough to see the blue rings of my eyes as I say something ugly. I never liked that ending either. More love streaming out the wrong way, and I don’t want to be the kind that says the wrong way. But it doesn’t work, these erasures, this constant refolding of the pleats. There were some nice parts, sure, all lemondrop and mellonball, laughing in silk pajamas and the grains of sugar on the toast, love love or whatever, take a number. I’m sorry it’s such a lousy story.

The poetic form of the litany (a kind of list) is perfect for this book and for Siken’s voice. He is at once aphoristic, painterly, and obsessive in his approach. Phrases like “I never liked that ending either” are conspiratorial in the best way, and his fearless striking at big, screwball-heavy terms like “love” and “forgiveness” in this poem are brave and surprising and, as so many readers have said, accurate: painfully accurate in its emotional precision. This is the kind of poetry that so many of us aspire to write and to read: so definite it transcends its details and rises into the realm of the relatable.

But woe to the poets who begin in relatability and attempt to build their houses there. That’s the realm of Instagram poets, also beloved by the internet. But Siken is a literary poet whose work is enjoyed by poets and more general readers alike precisely because of the dance he’s able to do between his subject matter (here, obsession, desire, and memory) and the language and poetic techniques he uses to describe it. Many different kinds of readers are able to fall under a spell and emerge changed, torn apart.

You take the things you love / and tear them apart

Coming out and living as a queer person has changed a great deal since Siken’s book won the Yale Younger nearly 20 years ago, and has undoubtedly changed even further still since the 1980s and 1990s—years which Siken gestures toward in poems like his oft-quoted “A Primer for the Small Weird Loves”:

you are ready to die in this swimming pool because you wanted to touch his hands and lips and this means your life is over anyway. You’re in the eighth grade. You know these things... you know that a boy who likes boys is a dead boy, unless he keeps his mouth shut...

A New York Times writer recently watched Heartstopper with LGBTQ+ teens and asked them whether or not coming out felt like a relevant concept to their generation. One teen commented “I understand why they wrote Nick feeling like he needs to come out to everyone in order to actually be out. But I feel like it would be a better message to show that you don’t need to. You can just exist as an L.G.B.T. person.”

This attitude stands in such contrast to so much of the content explored in Crush and in opposition, of course, to history. And thank god. For characters like Isaac and legions of Heartstopper’s fans, Crush is history, not current events: a boy who likes boys is not a dead boy today. He’s a boy on a hit TV show. Or maybe he’s just a boy.

Related

Why We Need More Poetry in Hospitals—and on Television

What can poetry do? It can connect people, lead to real-world actions, and even function as a kind of weapon. It also, of course, makes us think and feel and see deeper than any exhortation to look ever could. Poetry’s power to heal is one of its most frequent anecdotal uses, as well—think how often you’ve heard the act of writing poetry likened to “thera…

What Maggie Smith Thinks About Her Viral Poem's Cameo on Primetime TV

PopPoetry is poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post! Let’s take a stroll through this beautiful shithole.

Siken has ruined me for poetry. He's an explosion of feeling. Who else holds such a charge?