What Maggie Smith Thinks About Her Viral Poem's Cameo on Primetime TV

"Good Bones" Brought Comfort on Madam Secretary and Around the World

PopPoetry is poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post! Let’s take a stroll through this beautiful shithole.

Have you read this poem before?

Good Bones

Life is short, though I keep this from my children.

Life is short, and I’ve shortened mine

in a thousand delicious, ill-advised ways,

a thousand deliciously ill-advised ways

I’ll keep from my children. The world is at least

fifty percent terrible, and that’s a conservative

estimate, though I keep this from my children.

For every bird there is a stone thrown at a bird.

For every loved child, a child broken, bagged,

sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children. I am trying

to sell them the world. Any decent realtor,

walking you through a real shithole, chirps on

about good bones: This place could be beautiful,

right? You could make this place beautiful.

If this is the first time you’ve seen this poem, you just read Maggie Smith’s “Good Bones.” Originally published in Waxwing just days after the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, “Good Bones” has become a kind of “barometer” for how bad things are in the world. Views of the poem online surged in the days after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, after the murder of British politician Jo Cox, and now during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, among other events.

The poem was also featured during Season 3 Episode 18 of Madam Secretary, the Téa Leoni-led political drama that aired on CBS from 2014–2019. Having “Good Bones” featured on television seemed to be an enormous moment for contemporary poetry, at least to me: Smith’s poem and its star turn in primetime was one of the major events that convinced me to eventually create PopPoetry after scribbling infrequent essays on pop culture and poetry for years. It took time, but I got here, and Maggie Smith deserves a large part of the credit.

Smith has hilariously referred to “Good Bones” as her “Freebird,” or in other words, the song everyone wants to hear whether the band wants to play it or not. That’s why I’m deeply grateful that she agreed to answer some questions for me about the poem and its star turn on television. But first, a bit about the poem and the Madam Secretary episode named after it.

Madam Secretary’s “Good Bones”

In this episode, fictional Secretary of State Elizabeth McCord (Téa Leoni) and her political team work to save victims of sex trafficking in another country. Without spoiling anything, their operation doesn’t go quite the way they’d hoped.

The show draws a clear line from the small evils to the larger ones, from the personal victimization of one young woman to large-scale sex trafficking on the international stage, just as Smith’s poem does with its image of a stone thrown at a bird and the idea of the whole world as a sometimes-shithole.

Near the end of the episode, McCord assembles her team in her office and acknowledges the depravity they’ve all seen in their line of work. The staff members are quick to apologize for their grief, but McCord is set on acknowledging it, and rightfully so. She taps into our sense of our own futility, something that Smith’s poem does very well. As a kind of tonic, Jay Whitman (Sebastian Arcelus) pulls a slip of paper from his wallet and reads the last half of Smith’s poem on camera, substituting Smith’s delightful “shithole” for the word “hellhole” to please the censors. But the result is still as moving and as revelatory as the poem always is.

Despite the horrors of the world, the show is quick to show us, there are still good people out there. We have the opportunity to tear everything down to the studs and build it up again. After this scene and after a long day at work, McCord and her husband see their budding activist children fired up about injustice and perceive a glimmer of hope for this blasted society. This is the duality that Smith’s poem describes. There are sex traffickers and there are teenagers fighting for a more just world. Both inhabit this marble simultaneously.

The poem has had and continues to have a long life since, and has been translated into other languages and reinterpreted for various media. Button Poetry made this beautiful poetry-in-motion video that highlights the inter-generational import of its message.

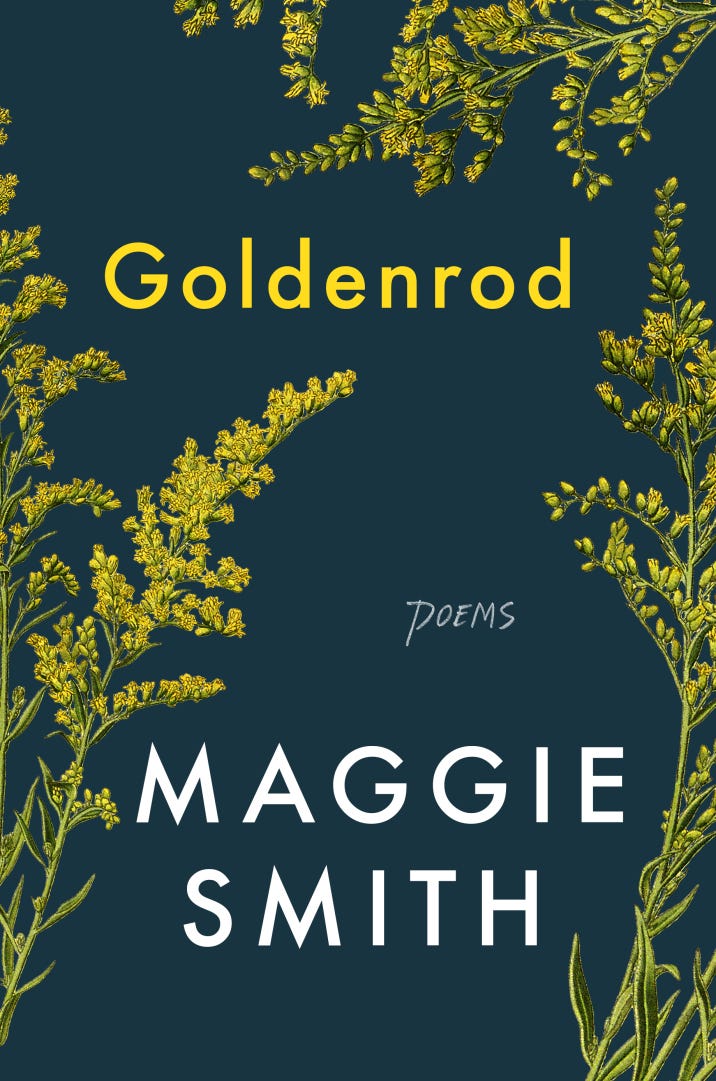

Though we were fond of calling 2016 “the worst year ever,” 2020 told us, defiantly, “hold my beer.” But instead of sinking deeper into despair, Smith described herself late last year as a “recovering pessimist.” She owes part of this change to the writing of her subsequent book, Keep Moving: Notes on Loss, Creativity, and Change. Borne out of her own notes-to-self on social media in the wake of a difficult divorce, Keep Moving contains the same hopeful spirit of “Good Bones” but steers even more directly toward the idea that we can and will determine the course of our own lives, and of life on our troubled planet. Her latest book, Goldenrod, will be published this summer and celebrates moments of hyper-presence that bloom into beauty in a sometimes-difficult world. You can pre-order it here.

I was dying to know what it was like to have a poem go viral and end up on TV, what her favorite poetry and pop culture crossovers were, and more. I’m very lucky to have been able to ask Maggie Smith these questions myself.

Brief Interviews with Luminous Poets: Maggie Smith on “Good Bones”

Caitlin Cowan: Thanks so much for answering some questions for me, Maggie. What’s it like, as a poet, to hear your work on a TV show? Watching the scene where Sebastian Arcelus reads your poem gave me chills, and I’m someone who’s read that poem countless times.

Maggie Smith: It was strange and surreal. I didn’t know exactly how the poem would be used—who would read it, where they might be, what would be happening in the episode, but I’d assumed—because of the way the poem went viral on the Internet—that it would be read off a screen. A computer in an office. An iPhone, maybe. But when the actor pulled a physical piece of paper out of his wallet, I lost it. It really hit me that the poem was important enough to his character that he printed it and carried it around with him.

CC: In one of the final scenes of the Madam Secretary episode named after your poem, Jay asks his colleagues, “Does any of this matter?” Later, Matt Mahoney (Geoffrey Arend) says that he doesn’t want to “play whack-a-mole with evil.” Your poem about selling the world to children seemed well-situated to enter this conversation. Does parenting, in some ways, feel like whack-a-mole to you? What about writing?

MS: Whack-a-mole as a metaphor feels right for the episode: you may solve one problem, but countless others are popping up all around you, and you simply aren’t fast enough and don’t have enough hands to handle them all. Thankfully this has not been my experience of either parenting or writing. These two things are what give me the most pleasure in my life, despite their challenges. Things don’t always turn out the way I’d hoped, but I feel equipped to handle the challenges. But also, I’ve been very lucky as a poet and as a mom.

CC: I spend a lot of time talking about tropes and stereotypes about poets and poetry, which I think are more rigid and pernicious than, say, tropes about painters or opera singers or novelists. What is the most frustrating stereotype about poets and poetry, to your mind?

MS: That we are all sad, tortured people.

CC: Do you have a favorite poem or poet that crops up in a TV show, film, or song? What about its appearance delights you?

MS: Perhaps it would be Sufjan Stevens’ reference to Carl Sandburg in “Come On! Feel the Illinoise!” (“I cried myself to sleep last night / And the ghost of Carl, he approached my window”). I love that Sandburg’s spirit—quite literally—is in this song. I also really admire Richard Buckner’s record The Hill, which is a gorgeous adaptation of Edgar Lee Master’s Spoon River Anthology. I remember seeing Buckner play those songs live and being absolutely transfixed.

CC: I’m interested in instances of poetry in popular culture because I think such interventions have the potential to mint new readers. But invariably, increasing the reach of poetry has the potential to alter the way that poets, poetry, and the public interact. Are there things that you enjoy about the “intimacy” of poetry as an art form and as a community? On the other hand, do you think there are there positives to increasing the approachability of poetry in our culture?

MS: I’ve always thought of being a poet as being part of a small club. A neighborhood treehouse gang. As poets, we have a smaller readership than, say, novels, but that small readership is passionate and discerning. Our readership, by and large, is each other—and yes, there is an intimacy in that. But of course I am all for widening that readership, not only because I would like poets to be able to support themselves more with their writing, but because I know what poetry can do. I wouldn’t be the same person—the same thinker, the same feeler, the same parent or lover or friend—without poems in my life, both writing them and reading them. I want more people to have that.

Maggie Smith is the author of five books, including Good Bones, Keep Moving, and a new collection of poems, Goldenrod, forthcoming from One Signal/Simon & Schuster in July 2021. Her poems and essays have appeared in the New York Times, The New Yorker, The Southern Review, the Guardian, the Paris Review, and The Best American Poetry. A freelance writer and editor, Smith is on the poetry faculty of Spalding University’s MFA program and serves as an Editor at Large for the Kenyon Review. You can find her on social media @MaggieSmithPoet.

P. S.

To recap: You can preorder Maggie’s newest book, Goldenrod, at this link. “Good Bones” appears in her collection of the same title, which you can purchase through Tupelo Press. You can also find local bookstores that carry her book Keep Moving: Notes on Loss, Creativity, and Change, at IndieBound.

Jennifer Benka, President of the Academy of American Poets, talked to Jeevika Verma on NPR’s Morning Edition about increased poetry readership during the pandemic.

Marianne Faithfull joins the legion of musicians who have turned to poetry during their careers.

As always, if you like what you read today, subscribe and share! It makes an enormous difference. Thank you for reading and engaging! See you next time.