The Mystical Austrian Poet Who Haunts The Weeknd's Dawn FM

On the singer's creepy-cool concept album, a poem penned around 1912 speaks volumes about the singer's existential views: a rare treat from one of the world's best-selling musical artists.

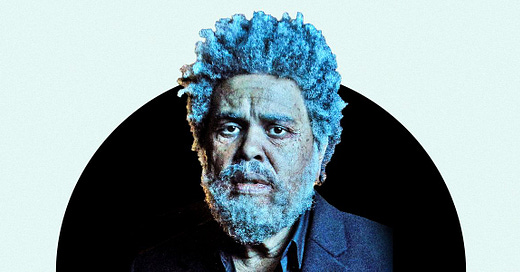

The Weeknd is an interesting guy. He doesn’t drop an album and leave it all on the record: he shows up bloodied, in bandages, with fake plastic surgery, and with artificially aged skin and gray hair during performances and live engagements. His public persona acts as a kind of poetic restatement of the themes of his work.

In an interview with Variety, The Weeknd, born Abel Tesfaye, explained the impetus behind this performance art, saying “The significance of the entire head bandages is reflecting on the absurd culture of Hollywood celebrity and people manipulating themselves for superficial reasons to please and be validated.” Tesfaye the man, rather than The Weeknd the performer, strikes me as someone who is committed to art in a way that transcends the role traditionally played by musicians.

Recently released Dawn FM, The Weeknd’s fifth full-length record, is a concept album, which is kind of like the project book of the music world. The album has a more rigid conceptual backbone than most records do, and knowing that concept deepens your engagement with the music. Dawn FM is configured as a radio station that plays in purgatory while one waits for their eternal fate. In an interview with Billboard, Tesfaye described it this way:

Picture the album being like the listener is dead. And they’re stuck in this purgatory state, which I always imagined would be like being stuck in traffic waiting to reach the light at the end of the tunnel. And while you’re stuck in traffic, they got a radio station playing in the car, with a radio host guiding you to the light and helping you transition to the other side.

In addition to intros and outros by Tesfaye’s friend (!) and neighbor (!!) Jim Carrey (!!!), Dawn FM also contains a translation of the opening lines of Rainer Maria Rilke’s first Duino Elegy and gives the song its name. Amazing, right? Shoutout to poet and educator Jennifer Whalen for catching me up on this pop culture and poetry marriage!

The interesting thing is that the translation doesn’t exactly correspond to any one of the most popular translations of Rilke’s work. Did he translate it himself? He is trilingual, though German isn’t one of the languages he’s fluent in. The mystery deepens! Let’s take a closer look.

Rilke & “Every Angel Is Terrifying”

The spoken word segment at the outset of Dawn FM’s Track 12, “Every Angel Is Terrifying,” is a translation of part of Rilke’s first Duino Elegy:

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ order?

Even if they pressed me against their heart, I’d be consumed

For beauty is the terror we endure

While we stand and wonder, we’re annihilatedEvery angel is terrifying

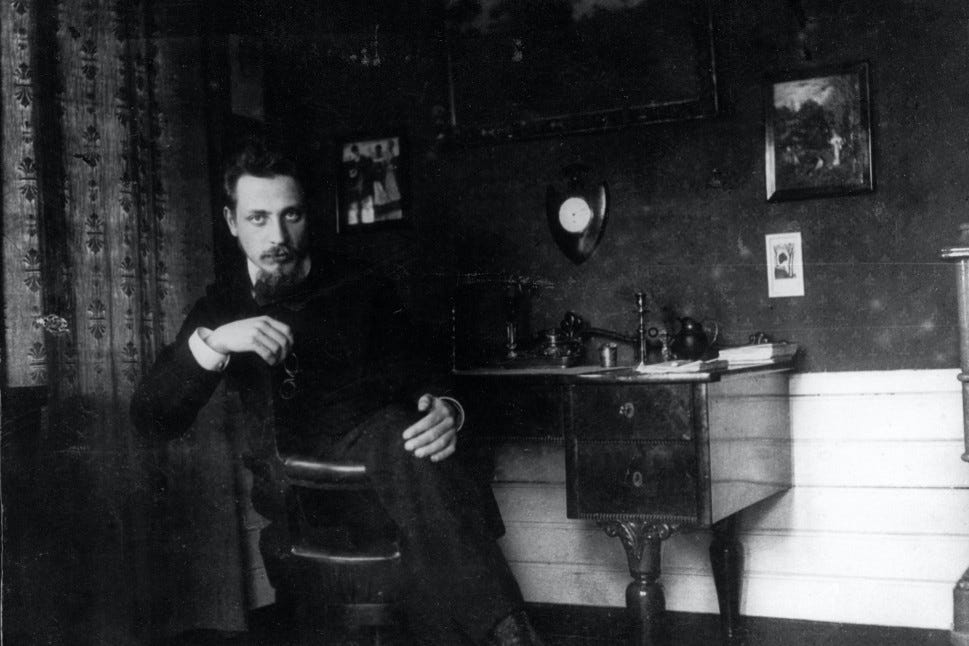

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) was a Austrian German-language poet whose writings continue to be immensely popular and powerful today, thanks to his enduring quotations, often favored by so-called “new age” thinkers, frequent pop culture quotations, and the posthumous publication of his wise and moving Letters to a Young Poet, which is exactly what it sounds like: a collection of letters Rilke wrote to a young fan and novice poet between 1902 and 1908.

In the context of The Weeknd’s afterlife-themed album, Rilke is a good fit because of the poet’s own preoccupations: the big stuff.

Rilke achieved that rare feat of popularity both during his lifetime and after. Ulrich Baer, Professor of Comparative Literature, German, and English at NYU, is recognized as one of the foremost Rilke scholars, and attempts to account for Rilke’s enduring popularity and quotability this way: “Rilke is one the few writers who gives us something like the very essence of poetry, which is to cast deeply felt emotions in highly resonant and memorably rhymed verse.”

In the context of The Weeknd’s afterlife-themed album in which terrestrial things are celebrated one last time before falling away into the eternal, Rilke is a good fit because of the poet’s own preoccupations: the big stuff. Baer puts it this way:

Rilke thought that only two experiences get us close to the authentic nature of our existence: love and death, experienced as loss. Poetry can console by capturing loss in ways that seem to give the painful absence a place in time, which the poem represents via the wave-like pattern of rhymed speech. Poetry does not let us “get over” loss but shows how to integrate loss into existence without letting us become overwhelmed by it.

How Did Rilke End Up on the Album?

Probably through The Weeknd’s co-writer: composer Oneohtrix Point Never, otherwise known as Daniel Lopatin. In a 2020 Rolling Stone article, director Nate Boyce relates a story about how Lopatin offered him a copy of one of Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet (which he refers to as “Fear of the Inexplicable”) when they were shooting the music video for “No Nightmares,” a Oneohtrix Point Never track featuring The Weeknd.

This is the Rilke excerpt that Lopatin offered to Boyce, which, as it happens, is still a good touchstone and possible inspiration, one might imagine, for the themes of Tesfaye’s Dawn FM:

The tendency of people to be fearful of those experiences they call apparitions or assign to the “spirit world,” including death, has done infinite harm to life. All these things so naturally related to us have been driven away through our daily resistance to them, to the point where our capacity to sense them has atrophied… Fear of the unexplainable has not only impoverished our inner lives, but also diminished relations between people; these have been dragged, so to speak, from the river of infinite possibilities and stuck on the dry bank where nothing happens. For it is not only sluggishness that makes human relations so unspeakably monotonous, it is the aversion to any new, unforeseen experience we are not sure we can handle.

So what does the Rilke excerpt that The Weeknd chose to turn into “Every Angel Is Terrifying” have to say about the album overall? To answer that question, we have to first consider the element of translation.

Three Four Translations

Rilke’s first Duino Elegy, written in a fever of sudden inspiration at Duino Castle outside Trieste, Italy in 1912, reads this way in its original German:

Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel

Ordnungen? und gesetzt selbst, es nähme

einer mich plötzlich ans Herz: ich verginge von seinem

stärkeren Dasein. Denn das Schöne ist nichts

als des Schrecklichen Anfang, den wir noch grade ertragen,

und wir bewundern es so, weil es gelassen verschmäht,

uns zu zerstören. Ein jeder Engel ist schrecklich.

Unless you speak German, we’ll need to translate. Rilke’s work has, of course, been translated endlessly into many languages over the years. The first-ever English translation is set to be reissued for the first time in more than 90 years later this month, and I’m dying to get my hands on it: this translation, translated by Vita and Edward Sackville-West, was first published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press (yeah, that Virginia Woolf and her lover, Vita). Until then, we’ll work with some other popular English translations.

Below are translations of the portion of the opening of the first elegy quoted by The Weeknd from three of the most well-known and respected translations of Rilke. You can check out these books in the footnotes.

Stephen Mitchell

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’

hierarchies? and even if one of them pressed me

suddenly against his heart: I would be consumed

in that overwhelming existence. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we still are just able to endure,

and we are so awed because it serenely disdains

to annihilate us. Every angel is terrifying.1

Edward Snow

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic

orders? And even if one of them pressed me

suddenly to his heart: I’d be consumed

in his stronger existence. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we can just barely endure,

and we stand in awe of it as it coolly disdains

to destroy us. Every angel is terrifying.2

Alfred Corn

For who, if I cried out, would ever hear me among the angels

and archangels? And even if one of them did suddenly

crush me against his heart, I would dissolve, undone by his more

strongly grounded being. For the beautiful is nothing other

than the onset of what is terrifying, something we just barely withstand,

and we’re struck with wonder at how calmly it disdains

to destroy us. Every one of the angels is terrifying.3

You’ll notice that these translations differ in their diction, or word choice, at some interesting points, particularly when it comes to the “pressed/crushed” distinction in lines 2–3, the difficult “overwhelming/stronger existence” (which Corn clunkily insists on translating as “more strongly grounded being”), and the “coolly/calmly/serenely” trifecta in the final lines. These small shades of meaning all offer slightly different flavors, and these choices are at the heart of translation work. The choices each translator makes are, in part, a representation of what he understands to be most important in the text.

For our purposes, the most striking thing to learn is that The Weeknd’s translation is not a direct translation of any of these, and is instead a pared-down version that cuts right to the scary heart of Rilke’s poem of death and horrifying angels: the idea that what sustains us, beauty and our pursuit of the good, has the power to ultimately destroy us.

It’s not clear how Tesfaye and Lopatin arrived at this translation, but they aren’t merely using Google translate. Just take the final word of the excerpt, schrecklich. A direct translation of this German word is “terrible,” which translators widely agree to translate as “terrifying” because of the way the word would have been used and understood in Rilke’s time.

This delicate work of balancing context and history is also a core consideration of translation, and it’s evident that the duo are either working from one of these translations and cutting out the parts that don’t speak to them or are enacting their own translation. There’s no evidence that either Tesfaye or Lopatin speak German, so it’s likely that they decoupaged their own translation to suit their purposes. The result is a spoken-word intro that speaks to the album’s themes of life and death but also nods to pop history and Afrofuturism.

Life, Death, and Afterlife

Rilke was a poet entranced by the mystical and the religious, and an excellent fit as a touchstone on The Weeknd’s fifth album. But Dawn FM also has other ancestors whispering to it, too. The album has an almost Afrofuturist bent, if we imagine the “future” in question to be less outer space and more inner space—the future that we all will share: death. In the words of Dr. Kathy Brown, “Afrofuturism is about forward thinking as well as backward thinking. Having a distressing past, a distressing present, but still looking forward to thriving in the future.” Some Afrofuturist writers and artists have envisioned this thriving future as taking place in another location in the cosmos, like Sun Ra.

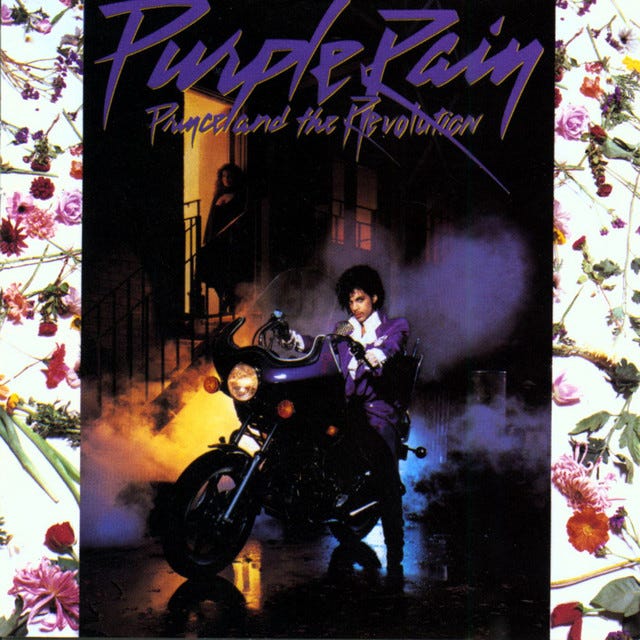

But The Weeknd isn’t the only Black artist to darkly imagine that thriving future as the afterlife. Tesfaye and Lopatin’s “Every Angel Is Terrifying” has the cadence and ceremony of another famous pop music invocation. Does this sound familiar?

Dearly beloved

We are gathered here today

To get through this thing called “life”

Electric word, life

It means forever and that’s a mighty long time

But I’m here to tell you there’s something else

The afterworld

This, of course, is the storied opening to Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy,” Track 1 Side 1 from his groundbreaking 1984 album, Purple Rain.

By tapping inspirations as diverse as Rilke and Prince, The Weeknd has joined the far and near past with his own futuristic vision on “Every Angel Is Terrifying” and Dawn FM more broadly. We learn all over again that The Weeknd’s lyricism and vision are second-to-none in the world of chart-topping music.

As a poet, I’m thrilled and grateful to see Rilke here, and I think he’s a perfect fit. Carl Wilson at Slate calls The Weeknd’s use of Rilke a “feint” (the Rilke translation is followed by far more contemporary language on Track 12, including “Critics say ‘After Life’ makes your current life look like a total comatose snooze fest”), but I would argue that raising the specter of the Austrian poet here is a smart choice which reminds us that no matter how terrifying it might be, we all have to face what’s next. So we might as well party on the way there.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Duino Elegies & Sonnets to Orpheus. Trans. Stephen Mitchell. New York: Random House, 1982.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Duino Elegies: Bilingual Edition. Trans. Edward Snow. New York: North Point Press/FSG, 2000.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Duino Elegies: A New and Complete Translation. Trans. Alfred Corn. New York: Norton, 2021.

Wasn’t aware of the new album (not my taste), but I did watch the short film on Prime of Weeknd singing songs from it in a dreamy setting with dancers: very interesting.

I think I’d go with Corn’s translation as slightly better English poetry. I like how he expands “Ordnungen” to list two types of angels (Mitchell’s “angels’ hierarchies” is unpoetic). Similarly, I feel Mitchell’s “in that overwhelming existence” and Snow’s “in his stronger existence” sound a little pretentious if you read them aloud. Corn’s “strongly grounded being” doesn’t sound great either, but at least it’s not so abstract.

Fortunately the German is not rhymed or in meter, so the translators didn’t have to deal with that. I never realized Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo” was a sonnet until recently because the early translation I have (Norton) drops the rhyme and strict meter.

The English “terrible” has also changed over the years, I suppose, from Battle Hymn of the Republic’s “terrible swift sword” (doesn’t mean the sword is shoddily made), and perhaps that’s the sense intended in the translation dictionaries. So, yeah, “terrifying” is good.

Minor typo alert: should be “angels” not “angles” in Corn’s last line. Although in a pool hall, if you’re losing money, every angle could be terrifying.