The Torture & The Poets of Taylor Swift's The Tortured Poets Department

The Chairman of TTPD needs a sabbatical in the worst way.

It’s National Poetry Month! If you feel like this writing on poetry and pop culture has added value to your life, I’d be so grateful to have you consider supporting my work further by becoming a paid subscriber. Beyond supporting me, an only somewhat tortured poet, your dollars also allow me to pay guest writers and make the future of this publication possible. Click the button below to celebrate NaPoMo by subscribing:

At long last, it’s here: The new album by one of the world’s best-selling musical artists, and it’s got “poet” right there in the title. This has, predictably, stirred up those among us who identify as poets.

Poets Eileen Myles, Richard Siken, Gregory Pardlo, and others weighed in at The New York Times, and countless others are discussing and memeifying the album on social media (myself included: I already went deep on my distaste for Swift’s Spotify “library” installation in L.A. last week, if you’d like to tug on that particular thread).

Critics are also weighing in, and some with less tact than others—under the protective veil of an anonymous byline, one Paste writer began their article with the cruel and sophomoric line, “Sylvia Plath did not stick her head in an oven for this!” Days after the album’s release, the entire ouroboric cultural apparatus has begun to eat itself: appetite for reviews peaked and plummeted on an incredibly accelerated timeline.

Even so, you know I’m going to weigh in on the album too, as I promised I would back in February when TTPD was announced. It’s not every day that your wheelhouse becomes a national and international flash point.

Though we’re predisposed to dislike the moody 11th album from a sad billionaire, I’m afraid to report that TTPD sadly earns this derision. The album is too long, too one-note, and doesn’t showcase Swift’s considerable lyrical talent as much as you’d think an album with “poet” in the title would.

The Title

Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department sparked a grammatical debate the moment it was announced, thanks to its lack of punctuation. It’s funny that the very first thing we did as a culture when confronted with a title referencing poetry and poets was to attempt to take refuge in prescriptive grammar, as if poets weren’t the most creative interpreters of what language—and all its “rules”—can do.

Would we have been as inclined to critique the title’s grammar on the world stage if it were called The Tortured Artists Department? Or what about if it were called The Happy Mathematicians Department (another Article + Adjective + Noun + “Department” construction)?

I ask because there is a long history of the culture at large debating whether something is or is not poetry, or whether it qualifies as poetry. When there’s paint on a canvas, no one ever says “That’s not a painting.” See, for example, harsh critics of Rothko: though they believe that a child could have done what he did, they don’t typically argue that his work is not painting: they just say that it isn’t good or that it is devoid of meaning (I think they’re wrong, but this isn’t a painting Substack).

Since we love to critique the usage of grammar and the existence of poetry, the two combining in this particular cultural moment feels suspicious to me: we’re way too ready to hate on this title and the album’s contents because of our cultural biases, not just because some of us find Taylor Swift exhausting or mediocre.

As for a “final ruling” on the grammar of the album’s title, as Sarah Rutledge wrote at Slate, there isn’t a cut-and-dry answer, which infuriates those who love to point out rule breakers.

Here is my ruling, as a professional copy editor: The album punctuation is fine as is. There are differing schools of thought on this, depending on what style guide you’re following (and persuasive arguments to be made either way), but according to the style guidance of both Slate and the Associated Press, the word poets is functioning here as a descriptive, not possessive, modifier of department. That is, you could think of this academic department as one for tortured poets. It’s a department that contains those poets, but, as most English majors can attest, it’s not actually owned by those poets. Individual poets cycle through; the department endures.

Many cling to grammar and rules because it feels protective, but in the end, prescriptive grammar is a classist, patriarchal, and racist construction that attempts to put the wild mare of language in a tidy paddock. But that beauty wants more, and she wants it bad.

So does Ms. Swift, if you’re nasty.

The Poets (and the Poetry)

The question of whether or not song lyrics are poetry is as old as time, and ultimately, it’s not a very interesting distinction. As I’ve often articulated, the only person who gets to determine whether or not something “counts” as poetry is the person who wrote it: whether that’s a pop star or a lauded literary poet.

Susannah Young-ah Gottlieb, Director of the Poetry & Poetics Colloquium at Northwestern University has affirmed the irrelevance of the “Is it poetry” question when it comes to TTPD:

I am pretty ecumenical in my relationship to cultural production… Some say there’s a distinction between lyrics and poetry. I’m not among them. Donne, Auden were set to music at times. Rap is an inheritor of Old English stress forms. Some lyrics, taken without music, might read like banalities — “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” even the Great American Songbook. A lot of people want to say poetry is the more rigorous form. They are more comfortable saying that a bad lyric is not poetry rather than, well… bad poetry. To me, everything about the distinction is not interesting enough to justify it.

Are song lyrics poetry? Let’s not gatekeep: classifications like genre and discipline are, ultimately, not very interesting. Is Swift a poet? That’s up to her to decide.

On the album’s title track, we get the most direct reference to poets other than Swift (if you’re inclined to think of her that way):

I laughed in your face and said "You're not Dylan Thomas, I'm not Patti Smith This ain't the Chelsea Hotel, we'rе modern idiots"

Ah yes, Dylan Thomas: one of the English-speaking world’s most well-known literary poets who is often associated with the “tortured” trope, having battled alcoholism and dying young. Check.

But Patti Smith! There’s a worthy model for Swift if there ever was one. In addition to her groundbreaking music, Smith has authored several nonfiction and poetry books, including the wonderful Auguries of Innocence (2005). Smith is that rare bird who has earned the respect of both musicians and poets alike—her words are luminous on the page and off. Part of the way Smith has accomplished this feat, to my mind, is not in keeping her lyricism and her poetry in pure categories, but by situating herself as a thinker, someone who is interested in the art forms on their own terms, for what they can do as vehicles for her language and her sharp mind.

It has to be said: the question isn’t whether Swift should write a book, but what topics she has other than her own heartbreak. The poets she namechecks had their own styles and preoccupations, but their work is much more varied in theme, approach, and discourse.

On the topic of so-called “page” poetry, there are two honest-to-goodness poems written by musical artists attached to this album: one by Swift, and one by none other than Stevie Nicks.

Both poems tell decent little stories, and both are disappointing in their use of language for different reasons.

In Swift’s poem, you can almost feel the way that language is leading her around by the nose. Look at the opening, for example:

At this hearing I stand before my fellow members of the Tortured Poets Department With a summary of my findings A debrief, a detailed rewinding For the purpose of warning For the sake of reminding As you might all unfortunately recall I had been struck with a case of a restricted humanity

The cart is before the horse, here, and the string of gerunds trots us into a big clunky abstraction: “restricted humanity.” Where is the music of the language? The surprise? The color and image and light and play? Later, we get this:

I screamed while bringing my fists to my coffee ringed desk. It was a mutual manic phase. It was self harm. It was house and then cardiac arrest.

Layering two clichés within a song feels momentarily clever: when we see it on the page it feels like first-though refuse. Songs allow for the musical backing to alter the tone and complexity of the language and allow the language to be offered only momentarily. On the page, the words are just there: right there. We can live inside them. As for the phrase “It was house and then cardiac arrest,” there just isn’t enough to do inside the line. It’s closed off and hollow because of its well-worn usage.

Or consider a line like “Spring sprung forth with dazzling freedom hues.” We get a cliché and an abstraction in close proximity: sprung spring and “freedom.” If Swift were in my classroom, I’d offer her an opportunity to elaborate on what a “freedom hue” is. I can’t see it. And while “show don’t tell” is such old advice that we’ve come to abhor it, this feels like a textbook example of when it’s needed.

Nicks’s poem has the opposite problem, and offers heaps of feeling with anesthetized language: “broken hearted,” joy, tragedy, clouds, truth, “too hot to handle.” These abstractions and clichés dull the power of the story Nicks is trying to tell. Adding music might add more dimension, but here the language falls flat, though having Stevie Nicks support you is a big-time pat on the back for Swift.

The Torture

The torture in question on this album has mostly to do with failed relationships. Again. Of course.

There are some brief forays into topics of distaste for fame and the singer’s (speaker’s?) own toughness, but mainly it’s the brokenheartedness that has made headlines and has filled the minutes of this album and its 15-song Anthology counterpart. One could argue that the emotional torture the singer endures is replicated by asking listeners to meditate on breakups for 31 songs spanning 2+ hours.

Critics have noted that Swift needed an editor to pare some of this back. When Drake released his chart-topping Scorpion double album, critics said the same thing. As a Drake fan, I enjoyed the album even though it admittedly wasn’t all hits. And I also think that’s what’s going on here: Taylor may be scraping the bottom of the barrel, but fans will undoubtedly find things to love, here. (I do think “Fortnight” is a bop).

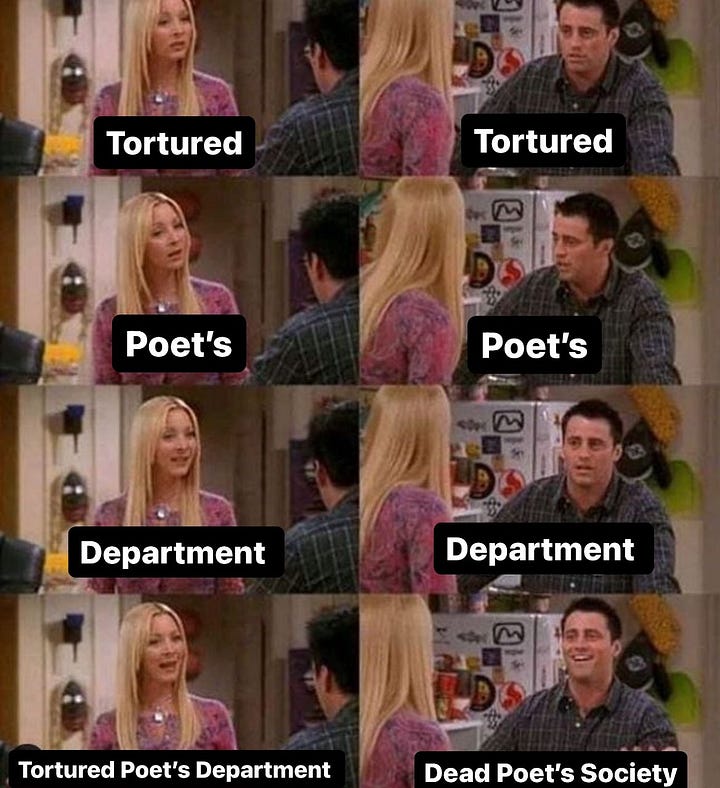

Some have joked about Taylor’s possible co-opting of Dead Poets Society, the well-known 1989 film. Swift has seemingly acknowledged her appreciation of the film and the comparison by casting Ethan Hawke & Josh Charles in the music video for “Fortnight,” too. But where Dead Poets Society takes on actual death, TTPD invokes “torture” as a metaphor for emotional pain and, whether on purpose or inadvertantly, bolsters stereotypes poets have long tried to distance themselves from and disprove: the hard-drinking tragic figure like that of Dylan Thomas and the beret-wearing Beatnik who’s just so deep, man, like that of Judy Funnie.

It is worth thinking, too of what it means to use the word torture in a time when genocide and war are raging. Ukraine posted its own “Tortured Poets Department” on social media, which contained the names of writers who had been killed during the ongoing war with Russia. It’s hard to argue with the fact that there are poets writing today whose very lives are in danger or have been taken from them, and when you set this album against the atrocities of our time… well, it feels weird for a wealthy white musical artist to start poking around this corner of the culture.

Adrian Matejka, poet and EIC of Poetry magazine, has said that he’d like to see Taylor “do for poetry what she did for Travis Kelce.” I can’t agree more. And what if we took it a step further: what could she do for poets in peril? What will the world’s most famous musical artist do with her billions? With her emotional baggage? With her bigass carbon footprint?

What I wouldn’t give to hear an album, or read some poems by Taylor Swift, about all that instead of one about boys and broken hearts.

Related

Taylor Swift's "The Lakes" Gets Romantic (Poetry, That Is)

PopPoetry is poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox weekly, subscribe below so you won’t miss a post! Thanks for reading and sharing. If you’d told me five years ago that I’d be blogging about Taylor Swift’s reference to Romantic Poetry, I would have slapped your cardigan out of your…

A Grand Unified Theory of Taylor: An Interview with Amy Long of Taylor Swift as Books

I had the pleasure of Zooming with dedicated literary citizen and big-time Swiftie Amy Long, creator of the delightful Taylor Swift as Books recently. I’ve been a big fan of TSAB for a while now, and it was wonderful to chat with a fellow writer who shared my goal of increasing the coolness and accessibility of literature. For the uninitiated, TSAB is an…