The Late Sinéad O'Connor Made an Old Poem into Something New & Throbbing

"I Am Stretched on Your Grave" is as subversive and deeply Irish in character as the singer was herself.

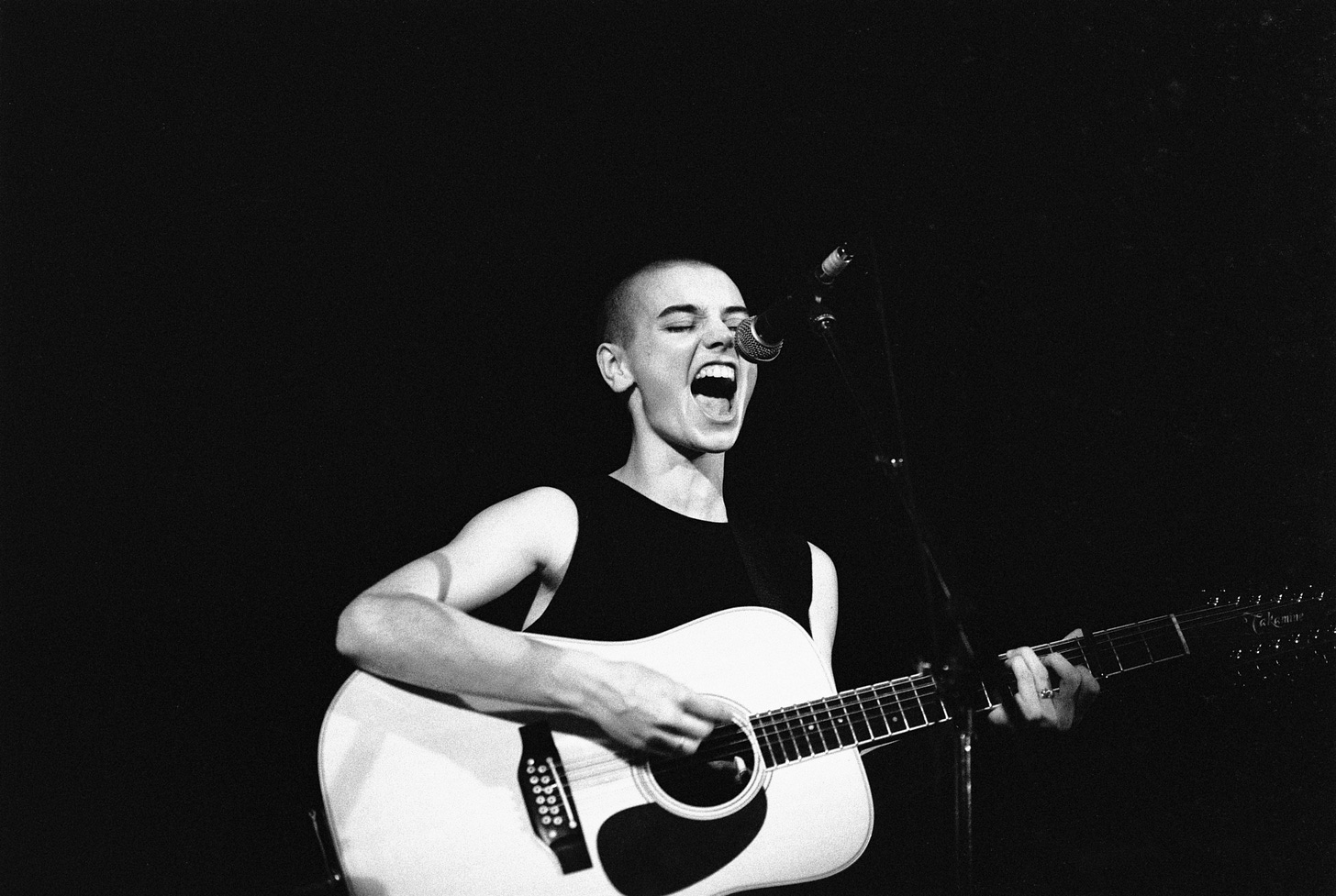

Last week the world lost a fierce talent in Sinéad Marie Bernadette O’Connor (still known professionally by that name, she changed her legal name to Shuhada Sadaqat in 2018 after converting to Islam). Her unmistakable voice and look were striking on the surface, and in the depths, the woman most knew as Sinéad O’Connor possessed righteous anger and a fearless magnetism for controversy.

For years the media seemed to feel that because O’Connor had suffered with abuse and mental health challenges herself that she was not fit to criticize those who caused suffering in the religious community. While conversations about O’Connor’s legacy will continue to develop in the months and years following her death, what’s easier to parse are the haunting songs she left behind.

Her sophomore album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, contains her most famous song alongside many other gems and fan favorites. One such song is based on a poem.

I just learned this fact recently and had typed the song’s name into my list of sources to revisit just days before she passed. I hate that this is how I’m returning to her music, and the reason why. But here we are. Let’s hear her sing to us again, and always.

My Grief for the Girl / That I Loved as a Child

The history of the song is complicated. At the root, “I Am Stretched on Your Grave” is based on a 17th-century Irish poem known as “Táim Sinte ar do Thuama.” The poem has been translated into English frequently. Here’s a well-known translation by writer Frank O’Connor (no relation) that informs Sinéad O’Connor’s song:

I Am Stretched On Your Grave I am stretched on your grave And will lie there forever If your hands were in mine I’d be sure we’d not sever My apple tree my brightness It’s time we were together For I smell of the earth And am worn by the weather When my family thinks That I’m safe in my bed From night until morning I am stretched at your head Calling out to the air With tears hot and wild My grief for the girl That I loved as a child Do you remember The night we were lost In the shade of the blackthorn And the chill of the frost Thanks be to Jesus We did what was right And your maiden head still Is your pillar of light The priests and the friars Approach me in dread Because I still love you My love and you’re dead I still would be your shelter Through rain and through storm And with you in your cold grave I cannot sleep warm So I’m stretched on your grave And will lie there forever If your hands were in mine I’d be sure we’d not sever My apple tree my brightness It’s time we were together For I smell of the earth And am worn by the weather

Sinéad (I’ll refer to her this way to avoid confusion with Frank O’Connor) wasn’t the first to adapt the poem into song—not by a long shot. In fact, it wasn’t the poem itself but the song adaptation by Irish folk rock band Scullion that she credits for the song on her album.

Written from a male point of view, Philip King of Scullion didn’t change the pronouns of the poem for his version of the song. An interesting facet of Sinéad’s version is that she, too, declines to alter the gender of the speaker of the poem—but this has a much different valence for her than it did for King.

I Still Love You / My Love and You’re Dead

In her most famous song, a cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U,” she changes the gender of the speaker to align with her own presentation. Prince sings:

I could put my arms around every girl I see

But they’d only remind me of you

I went to the doctor and guess what he told me

Guess what he told me

He said, “Boy, you better try to have fun no matter what you do”

But Sinéad changed it to this:

I could put my arms around every boy I see

But they’d only remind me of you

I went to the doctor, guess what he told me

Guess what he told me

He said, “Girl you better try to have fun, no matter what you do”

She doesn’t follow this pattern when it comes to “I Am Stretched on Your Grave.”

Instead, she leaves the pronouns as-is, singing about the “girl” that she loved as a child. This queers the song and highlights how extra creepy and purity-obsessed this section is:

Do you remember The night we were lost In the shade of the blackthorn And the chill of the frost Thanks be to Jesus We did what was right And your maiden head still Is your pillar of light

The sonic landscape of the song is also incredible: where Scullion went for something more straightforward that honored the poem’s roots, Sinéad sang over a sample from James Brown’s “Funky Drummer.” The song is pulsating and sexual and powerful, full of the romantic weird mythos of Ireland and shot through with uncomfortable religious subtext.

It’s really something else.

The near-suicidal devotion of the speaker to the deceased is reminiscent of Poe’s “Annabel Lee,” famously set to music by Stevie Nicks, who also left the original pronouns in place when she adapted the work. When women like Sinéad and Stevie sing songs based on poetry written by men, the songs bloom into greater significance, and we’re invited to see the cracks in the patriarchal structures that inform them.

If all you know of Sinéad O’Connor are the headlines and the SNL fallout, this is your sign to delve deeper into her music, into the basis for her prescient criticism of church abuse, and into the history of Ireland, which is critical to O’Connor’s biography and her work. What you’ll find may be painful and filled with ghosts. But they’re ours to grapple with now that she’s gone. It’s our turn to carry it.

Very interesting and informative discussion of this moving poem that I know best from, yes, the incomparable Sinead's beautifully haunting version(s).