The Reluctant Witchy Icon Who Adapted a Poe Classic

Revisiting Stevie Nicks' "Annabel Lee," just in time for Scorpio season.

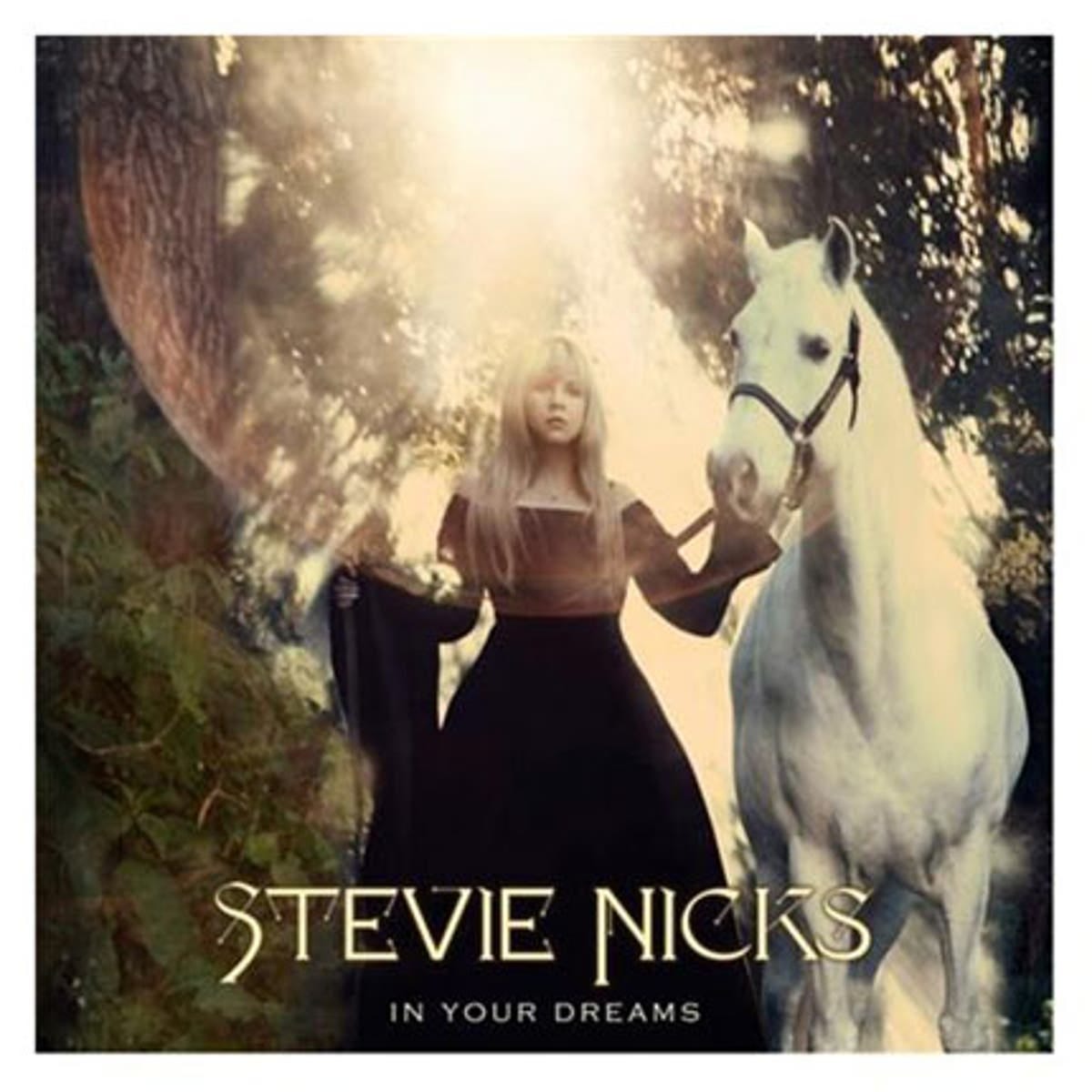

It’s a marriage made in heaven with a hint of something much darker: on her seventh album, In Your Dreams, Stevie Nicks recorded a song that takes as its source material one of Edgar Allan Poe’s best-known poems: “Annabel Lee.”

You know Poe: one of the most enduring 19th-century poets and the emblem of gothic American Romanticism. Poems like “The Raven” and short stories like “The Tell-Tale Heart” have cemented Poe’s legacy in American letters and made him an icon for those who love his gloomy, often spooky work.

You might also be familiar with “Annabel Lee,” the last poem that Poe completed during his lifetime. Published just after his death in 1849, the poem has gone on to be adapted by musicians like Joan Baez and Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, but has also been set to classical music and was even a core component of the 1995 PC game The Dark Eye (to which, interestingly, William S. Burroughs lent his voice). Today Stevie Nicks’ adaptation of the Poe poem is probably the best known, and studying it highlights some questions about the adaptation of poems into songs.

“Annabel” & Adaptations

Adapting poetry for music is a tricky business. Poems share many attributes with songs, but they aren’t songs. Some poems lend themselves to a rather straightforward adaptation process: if there is a repeated line or stanza, this can become a chorus quite easily, with other sections functioning as verses. But for poetry that is more free verse in nature—lacking any kind of formal scheme—musical artists have to decide how to square the art of songwriting with the art of poetry. Both use language and the sound of language to communicate their aesthetic and intellectual point of view, but songs typically hinge on repetition that may not be present in poetry. Therefore, songwriters have felt free to adapt the “raw material” of poetry in various ways.

In the case of Nicks’ Poe “cover,” a poem with plenty of repetition is transformed into a song that retains much of that repetition. But what’s interesting are the parts that Nicks chooses to omit and augment.

The album version of the song from In Your Dreams (2011) is slick and highly produced: a product of its time. A demo version of the song has circulated among fans for years, and I vastly prefer its 90s vibe and more straightforward instrumentation. Both have the same lyrics, which I’ll discuss here.

Nicks largely retains the first two stanzas of Poe’s poem as-is:

POE

It was many and many a year ago, In a kingdom by the sea, That a maiden there lived whom you may know By the name of Annabel Lee; And this maiden she lived with no other thought Than to love and be loved by me. I was a child and she was a child, In this kingdom by the sea, But we loved with a love that was more than love— I and my Annabel Lee— With a love that the wingèd seraphs of Heaven Coveted her and me.

NICKS

It was many and many a year ago In a kingdom by the sea That a maiden lived whom you may know By the name of Annabel Lee This maiden she lived with no other thought Than to love and be loved by me She was a child and I was a child In this kingdom by the sea But we loved with a love that was more than love I and my Annabel Lee With a love that the winged angels of Heaven They coveted her and me

In the first stanza, Nicks omits the word “there” from the third line and the word “and” from the fifth line. In the second stanza, she inverts the pronouns of the first line and swaps out “wingèd seraphs” for the more contemporary “winged angels.” These minor changes make the text a bit more easily understood by today’s audiences.

After this point, Nicks makes more aggressive changes. She eliminates the poem’s (somewhat tedious—there, I said it!) third stanza and inserts the first chorus she’s fashioned as a patchwork from the poem’s final stanza. Poe uses the stars in his final stanza, but in one of the only additions she makes whole cloth, Nicks uses the sun in her chorus:

And the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams And the sun never shines, but I see the bright eyes I lie down by the side

In his review of In Your Dreams, Rolling Stone’s Rob Sheffield astutely notes that “Poe’s key line — ‘The moon never beams without bringing me dreams’ — might have been written in 1849, but it was clearly meant for Stevie Nicks to sing.”

From here on out, Nicks is mainly faithful to the poem while inserting her created chorus and repeating snatches of the original poem.

What makes this adaptation successful is the fact that Nicks hones in on what interests her as a songwriter and as a singer and highlights those aspects of the original poem in her song version. The dreamy, haunted imagery of death, lost love, and the moon are all retained and burnished in Nicks’ “cover” of “Annabel Lee,” and Nicks’ song creates even more repetition than is present in the original by adding refrains to the end of the song:

I lie down by the side Of my darling, my life, my life and my bride I lie down, by her side I lie down, by her side My darling, my life, my life and my bride I lie down, by her side I lie down, by her side oohh I lie down, by the side oohh I lie down, by the side

In other words, Nicks honors Poe’s motifs and sound while still carving our space for her own signature Poe’s “Annabel Lee” has such a strong commitment to sound that it’s mournful cadences feel precariously close to song, but Nicks pushes the poem over the edge into new sonic territory.

Bonus: The Halloween Vibe

Despite her fame, Stevie Nicks is something of an enigma. She’s said that her sartorial choices are not meant to represent witchcraft, yet many baby witches have been enchanted by her style and songs. Despite the fact that she has a long witch-adjacent history, she was so bothered by these intimations of witchcraft that she stopped wearing black altogether for years. She has more recently embraced her witchy side by choosing to appear as the White Witch on American Horror Story: Coven. In a similar vein, Nicks’ sexuality was something fans questioned for years until she put the question to rest in a 2013 interview.

It seems that Stevie Nicks transcends Stevie Nicks, which must be a real bitch if you’re Stevie Nicks. She says she’s not a witch? Tough: she’s known as a witchy style icon. She says she’s straight? Tough: she’s a gay icon and rumors about her sexuality have swirled for years. And co-(re)writing “Annabel Lee”—a song adapted from America’s spooky poetic forefather about the death of a woman the speaker loved—bolsters her witchy cred and re-ups the frisson of queerness that some fans have picked up on over the years.

In short, this savvy adaptation cements Stevie Nicks’ status as everything she is and, quite possibly, everything we imagine her to be. Poe would be proud, I think, of this strange dance of poetry and song, and of identity and aesthetics.