Simon & Garfunkel's "Richard Cory" Misses the Mic Drop

More than just a sung version of the poem, the famous folk duo's song layers on sinister meaning but lacks the power of the original work's silence & finality.

“Richard Cory,” a poem by American poet Edward Arlington Robinson, belongs to a category I sometimes think of as the “mic drop” poems of the Western canon: verses that end on a sudden, brilliant, even shocking last line. Other entries in this genre include Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” James Wright’s “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota,” and Randall Jarrell’s “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.” These poems take up death and existential crises—deaths of the psyche, you might say—in their final moments.

These 19th and early- to mid-20th-century poems are written by white men. They’re beautiful, but they’re also almost violent, the last lines coming at you like punches. Their structure, tone, and didacticism are very much of their time. “Richard Cory” was groundbreaking in its style, both in terms of its narrativity and in terms of its bald, bold final line, and the poem has been deeply canonized, as have Robinson’s other “Tilbury Town” poems.

In short, “Richard Cory” is entrenched in American culture. What can it tell us in our own time, and how does a popular adaptation of the work into song change or complicate its resonance?

Everything a Man Could Want

Robinson’s “Richard Cory” tells the story of a man envied by all he knew. But unbeknownst to those around him, Cory’s life is not as charmed as it seems. Robinson describes Cory in plain-spoken lines manicured into a formal rhyme scheme—a style he’s known for.

*CW: Suicide and self-harm*

Richard Cory EDWIN ARLINGTON ROBINSON Whenever Richard Cory went down town, We people on the pavement looked at him: He was a gentleman from sole to crown, Clean favored, and imperially slim. And he was always quietly arrayed, And he was always human when he talked; But still he fluttered pulses when he said, "Good-morning," and he glittered when he walked. And he was rich—yes, richer than a king— And admirably schooled in every grace: In fine, we thought that he was everything To make us wish that we were in his place. So on we worked, and waited for the light, And went without the meat, and cursed the bread; And Richard Cory, one calm summer night, Went home and put a bullet through his head.

Robinson wrote other poems in this vein: prosy, focused on the story of a life, and full of reversals, like the sonnet “Reuben Bright,” but “Richard Cory” is far more arresting.

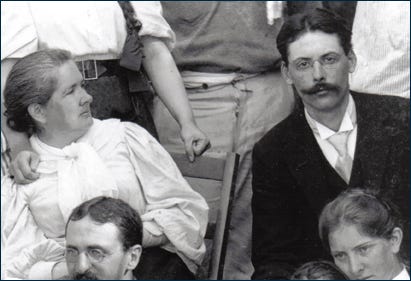

The poet was no stranger to difficulty himself, though he was, in the end, pulled up from this misery by friends, benefactors, and a heaping helping of good fortune. Robinson was deeply committed to poetry and wrote virtually nothing else in other genres. He was also a free verse skeptic, once quipping that he already wrote “badly enough as it is” without having the guideposts of form to aid him. He self-published two books of poetry that were not well-received, and he relied on his friends to bankroll him in stretches of poverty.

But just when he seemed poised to slip into permanent alcoholic self-pity, President Theodore Roosevelt’s son brought Robinson’s work to his father’s attention. Roosevelt ended up offering Robinson a job with a steady income that required very little work, thus securing his financial future and paving the way for future success as a writer able to focus almost entirely on his poems. You can’t make this shit up.

Still, Robinson’s work frequently deals with broken dreams and the tension between the public face and the private life. His work is curious about sorrow and regret and catalogs a host of human miseries with extreme accuracy and a good deal of pathos.

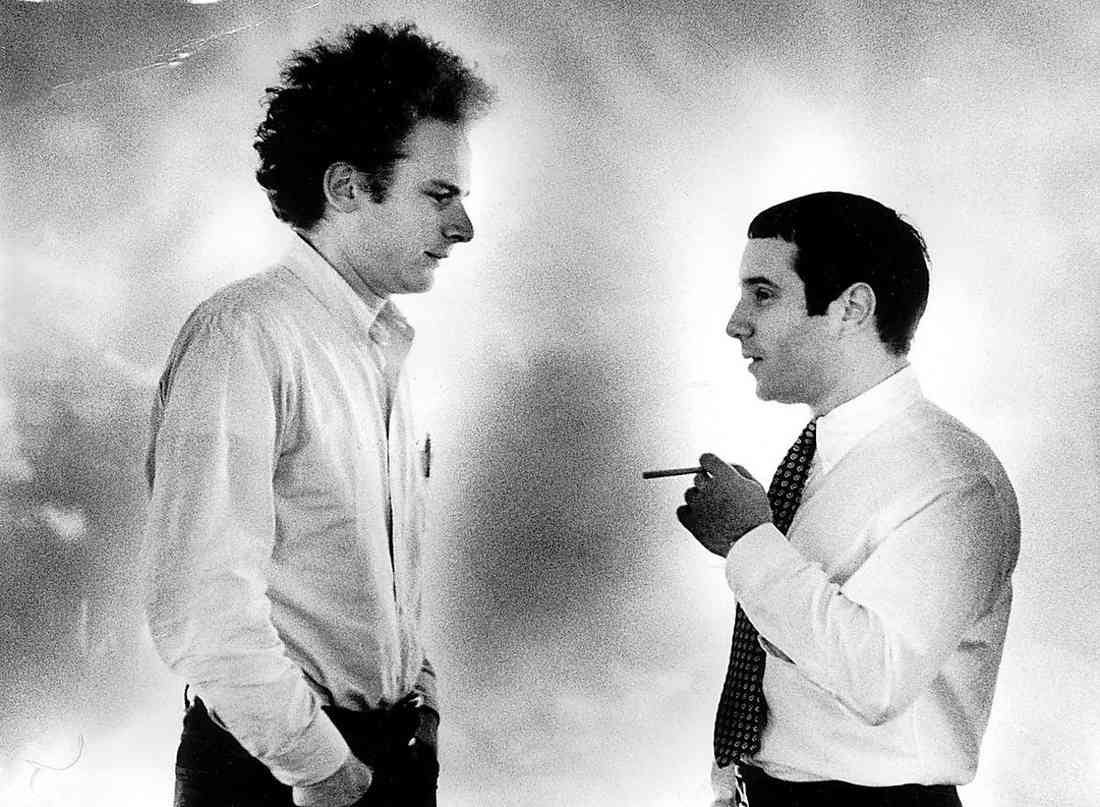

The highly narrative “Richard Cory: caught the eye of singer-songwriter Paul Simon between 1964 and 1965. Simon wrote the song “Richard Cory” for Simon & Garfunkel’s formative Sounds of Silence (1966). But rather than a sung version of the poem like Stevie Nicks’ “Annabel Lee,” Simon & Garfunkel’s “Richard Cory” is its own animal, written in entirely new languages except for a single line.

I bet you can guess which line it is.

However, the way Simon uses that line and the conclusions the song comes to are far different—and perhaps even darker—than those in the ether around Robinson’s poem. What the song lacks in surprise and silence it makes up for in other ways, creating a highly unique conversation between 19th-century American poetry and 20th-century popular culture.

We People on the Pavement

Simon & Garfunkel’s creation is an interesting little piece of theater: the singers imagine themselves as workers in Richard Cory’s factory and paint the man as a figure even more powerful and enviable than the Cory of Robinson’s poem. The envy is still there, as is Robinson’s ending, but the song doesn’t stop there.

You might expect a song based on this poem to be a dirge or one of the delicate, shimmering folk hymns Simon & Garfunkel were sometimes known for. But this sonic adaptation is jangly and upbeat, bouncy and driving, but its abundant minor and seventh chords hint at something ominous beneath the shiny surface.

Besides the shocking (if well-worn) phrase “put a bullet through his head,” the text of the poem and the lyrics of the song are totally dissimilar in terms of their language. And while the last line of Robinson’s poem does appear in the song, the song continues on afterward with another round of the chorus.

The most arresting feature of Robinson’s poem is the placement of the final revelation: in the very last line. After this pronouncement, nothing follows. There is only the silence of the finished poem, of the empty page.

“Richard Cory” is the kind of poem that takes it out of you, one you read and then have to stop and stare at the wall for a while afterward. The most arresting feature of Robinson’s poem is the placement of the final revelation: in the very last line. After this pronouncement, nothing follows. There is only the silence of the finished poem, of the empty page. Not so in the song.

Importantly, the point of Robinson’s poem is that we never know how much misery is endured by those we admire and envy. It’s a timeless issue that feels fresh in our age of social media and renewed discussions about what means to only post the positives.

But Simon & Garfunkel’s song continues on after the revelation that Richard Cory ended his life, and the singer still wishes that he “could be Richard Cory.” You might argue that the duo misunderstood or warped the song. But you might also argue that Simon & Garfunkel’s song offers an even more sinister truth: even if we knew how much suffering wealthy and well-liked people endure, we would still jump at the chance to have their lives, even if they were short-lived and ended in suicide.

Hi Caitlin,

Could you give me a free subscription for 3 months? Thanks. Current student on creative writing.