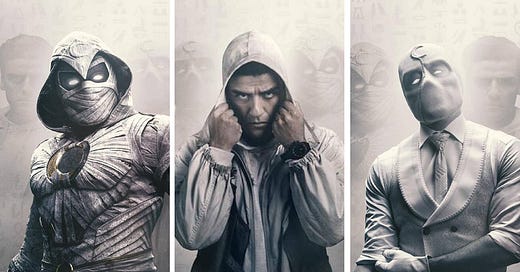

Oscar Isaac Said We Can Call Him Daddy AND He Recites French Poetry? Oof!

Moon Knight's second episode uses an obscure poet to draw two characters together and gives us the vapors in the process.

In a recent interview, “everyone’s internet husband” Oscar Isaac said that he wasn’t aware that fans referred to him as “daddy” but welcomed them to do so. Back at the top of our minds once again due to his starring role in Marvel’s latest Disney+ original miniseries Moon Knight, Isaac’s casting is proof that Marvel loves us and wants us to be happy.

I have seen every Marvel property with the exception of Thor: The Dark World, which my partner and I turned off because it was literally SO DARK (in the lighting sense, not in the spooky sense) and SO BORING that we nearly died. Still, I am decidedly a non-specialist. My partner is the one who rips through all the ultra-nerdy explainers on YouTube after consuming the latest offering from the obscenely successful media franchise.

But in my humblest opinion, Moon Knight is really good and exciting and stylish and makes me feel like a kid in the best way: I want a Moon Knight action figure. For TOTALLY NORMAL reasons. And just when I thought I couldn’t like it any more than I already did, they went and jammed some poetry into the show to boot. Bless you, Kevin Feige.

Bad Moon Rising

Moon Knight centers on British bloke Steven Grant (Oscar Isaac), a mild-mannered museum gift shop employee with a sleepwalking problem. To combat this, Steven chains himself to his bed every night to avoid wandering about.1 While this precaution protects his body, it doesn’t protect his mind: Steven experiences perplexing, vivid nightmares that begin to bleed into his reality, disrupting his otherwise bland existence. He begins to hear voices, and his reflections—whether they’re in mirrors, glass, puddles, or otherwise, begin to speak to him.

It becomes clear that Steven may actually have another identity: that of Marc Spector, a suave American. Through a series of bizarre events, Steven meets Layla (May Calamawy), who calls Steven “Marc” and says that she’s married to him. Steven has never seen her before in his life, but she insists that the two have a long history and doesn’t understand why Steven won’t “drop” his British accent.

As they try to grapple with their confusing relationship to one another, Layla and Steven end up reciting lines of the same poem together in Episode 2. What’s more, the poem is in French. I’ve written before about the power of poetry to become a shared language between people: poetry is itself heightened language, and when two people connect over a poem, it can be deeply bonding.

In other words, it’s kinda hot. I may need a moment. While I fan my brow, watch the scene below.

Steven/Marc’s flat is a book lover’s dream, crammed with books in every nook and cranny. When Layla approaches one of the bookshelves seemingly at random and sees a book she recognizes, she becomes suspicious. Her suspicion and her thrill are cranked up to 11 when Steven begins to recite a poem by the book’s author from memory in French.

The poet, Steven says, is his favorite. “Um, no, she’s my favorite,” Layla replies, utterly shocked. For two people who may not know one another to call the same obscure poet their favorite is, as Steven says, “mental.” The poem becomes a clue that Steven—or at least some version of him—and Layla do indeed have a past of some kind, however confusing it may be.

Poetry by Dead Men Women

The poem that Steven/Marc begins to recite in this episode is Marceline Desbordes-Valmore’s “Les Séparés.” Layla joins in, and the two eventually recite the first two lines together. The poem appears in French in its entirety below.

Les Séparés

N’écris pas. Je suis triste, et je voudrais m’éteindre.

Les beaux étés sans toi, c’est la nuit sans flambeau.

J’ai refermé mes bras qui ne peuvent t’atteindre,

Et frapper à mon cœur, c’est frapper au tombeau.

N’écris pas !

N’écris pas. N’apprenons qu’à mourir à nous-mêmes,

Ne demande qu’à Dieu... qu’à toi, si je t’aimais !

Au fond de ton absence écouter que tu m’aimes,

C’est entendre le ciel sans y monter jamais.

N’écris pas !

N’écris pas. Je te crains ; j’ai peur de ma mémoire ;

Elle a gardé ta voix qui m’appelle souvent.

Ne montre pas l’eau vive à qui ne peut la boire.

Une chère écriture est un portrait vivant.

N’écris pas !

N’écris pas ces deux mots que je n’ose plus lire :

Il semble que ta voix les répand sur mon cœur ;

Que je les vois brûler à travers ton sourire ;

Il semble qu’un baiser les empreint sur mon cœur.

N’écris pas !Don’t speak French? Don’t sweat it. Louis Simpson’s English translation of the poem appears here:

The Separated

Do not write. I am sad, and want my light put out.

Summers in your absence are as dark as a room.

I have closed my arms again. They must do without.

To knock at my heart is like knocking at a tomb.

Do not write!

Do not write. Let us learn to die as best we may.

Did I love you? Ask God. Ask yourself. Do you know?

To hear that you love me when you are far away,

Is like hearing from heaven and never to go.

Do not write!

Do not write. I fear you. I fear to remember,

For memory holds the voice I have often heard.

To the one who cannot drink, do not show water,

The beloved one’s picture in the handwritten word.

Do not write!

Do not write those gentle words that I dare not see,

It seems that your voice is spreading them on my heart,

Across your smile, on fire, they appear to me,

It seems that a kiss is printing them on my heart.

Do not write!Several writers have noted the poem’s appropriateness in terms of Layla and Steven’s apparently estranged relationship. Others have noted that Steven’s job at London’s National Art Gallery—which boasts several exhibits on ancient Egypt when we meet Steven—and the show’s core fascination with Egyptian gods and imagery is nicely evoked by Desbordes-Valmore’s use of the word “tomb” in line 4.

But most interesting to me is the idea that the separation Desbordes-Valmore describes in the poem calls to mind Steven’s fractured identity. In these first two episodes, we see Marc call out to Steven through the void, through his dreams and reflections. Are these two subjectivities mystically attempting to timeshare the same body? One man suffering from dissociative identity disorder? Is this a Fight Club homage?

No matter what the outcome of the show’s plot will ultimately be, reading Desbordes-Valmore’s poem as the speech of a person who longs to be whole in some fundamental way, whether romantically or literally, is deeply moving. The poem’s refrain, “Do not write!” functions as a poignant denial of what the speaker really wants: connection and completeness.

But if the speaker of the poem can’t have that completeness, it would rather not know about its other half at all. I’m sure Steven Grant can relate.

Who’s That Girl?

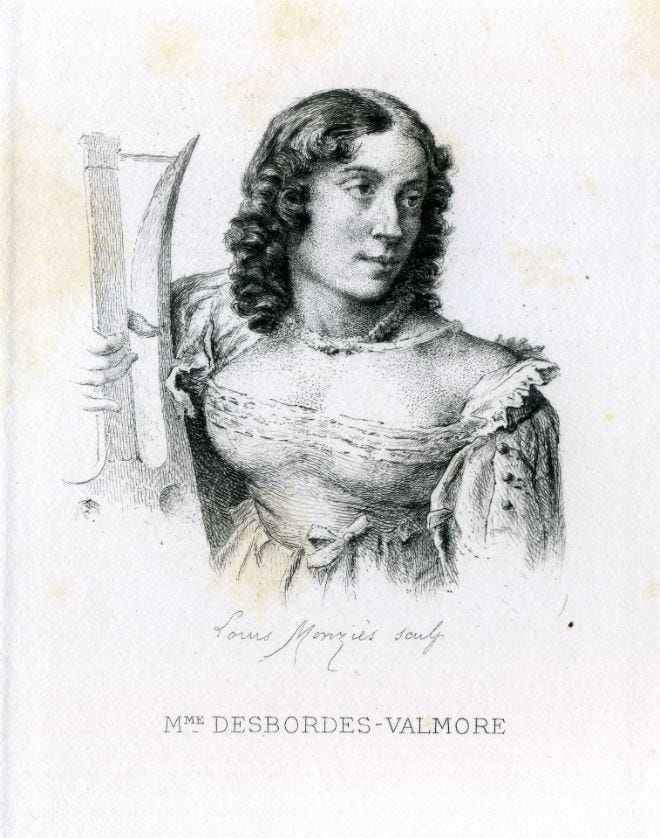

Marceline Desbordes-Valmore (1786-1859) is a wonderful and obscure French poet who was active in the Romantic era. She was a friend of Honoré de Balzac, was admired Baudelaire, and had her work anthologized by Paul Verlaine. Nietzsche was a fan. In other words, she has enjoyed an excellent, though limited reputation.

There’s no reason she isn’t more well known other than the fact that she’s a woman, one might say. Simone D. Ferguson has argued that Desbordes-Valmore was a trailblazer, stubbornly writing about women’s experiences in a naked way that would not be equaled until the arrival of writers like Plath, Rich, and Ostriker:

In an age where most women writers wrote, as they were expected to, “feminine works” such as little poems for children (which Desbordes-Valmore did write as a source of income) or disguised themselves by adopting a male pseudonym, Desbordes-Valmore wrote as a woman about a woman’s experience of life. She proclaimed her feminine identity through a strong and assertive “I”—the voice in all her poems.

Layla is a strong and captivating woman whose interest in Desbordes-Valmore may lie in her ability to personally identify, perhaps, with the writer and her subject matters. But Steven’s interest in the poet signals both his sensitivity and his relationship with Layla: one could imagine that he became interested in Desbordes-Valmore through Layla.

No matter what the truth is, the poem serves as a flashpoint of connection, a literal shared language, between two people It shows them that they can, in some fundamental way, trust one another. We’ll see where things go from here.

Moon Knight’s third episode airs today on Disney+. Happy watching!

Desbordes-Valmore’s work is hard to find in English, though Amazon does have one decent little volume in translation by Anna M. Evans on offer, which includes a translation of “Les Séparés.” For those who read French, many more options exist, though overall Desbordes-Valmore remains more obscure than many male writers of her age. Let me know if you own editions of her work that you treasure! I’d love to see them.

And don’t forget to share this post with the Marvel fans and poetry lovers in your life below!

Related

On this subject, I must defer to an excellent tweet from Alexis Nedd (@alexisthenedd):

Is D-V obscure among readers of French poetry, or do you mean among readers of poetry in English translation? If the latter, I would think all French poets are obscure in the sense that readers don’t have an aural connection to them. Although Simpson’s translation is quite readable and he preserves the rhyme, it probably doesn’t have the sonic impact of the original.

I had subtitles turned on for this episode. During the D-V recitation, it didn’t show the French or an English translation, just (RECITING POEM IN FRENCH). Similar to how they did the Spanish in the new West Side Story. Not helpful at all.

Knowing the meaning of this poem, even a gloss, would help explain Layla’s and Steven’s relationship. I wonder if on the big screen (or on Netflix), it would have been subtitled. Might be something to explore here in a future column, the whole translation / dubbing / subtitle dilemma, both for screen and page.