Loki and T. S. Eliot Walk into a Bar...

The poets and poetry of the Marvel show's Season 2 finale have a lot to say about the show's plot—and its star's literary habits.

While my husband and I were watching the Season 2 finale of Loki—which was recently (Cut us some slack! We have a toddler!)—my English PhD suddenly felt like it was highly relevant.

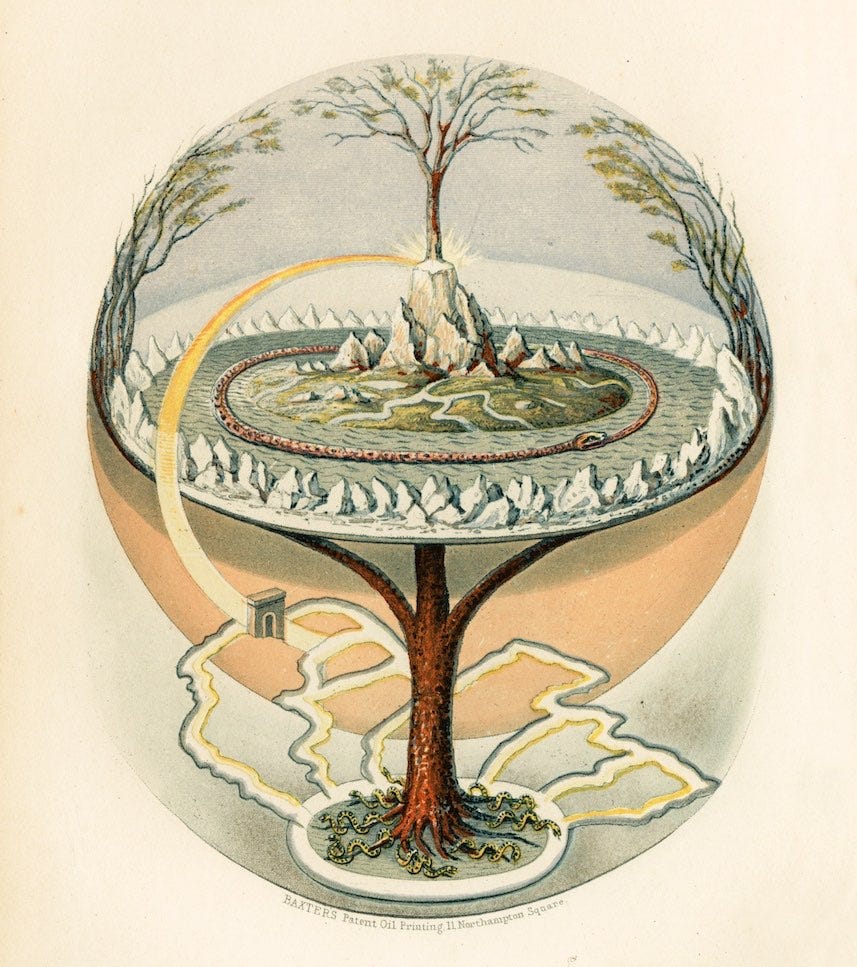

In Season 2 Episode 6, “Glorious Purpose,” we get a glimpse of a twisted, branching set of timelines that god of mischief Loki (Tom Hiddleston) can actually grasp, shape, and power. As the scene progresses, those branching timelines braid and grow together before flaring outward, and we see that their shape resembles a root system, a trunk, and leaves.

“It’s a tree! It’s the tree! Oh my god, it’s Yggdrasil!” Yes, I shouted and pointed at the TV like a good little meme.

I think Mr. PopPoetry must have thought I was the one who had grown horns. But what I saw on screen was a representation of Yggdrasil, or the World Tree from Norse mythology. This mythical ash tree was said to contain and connect all nine worlds in the cosmos. I learned of the tree and the narrative poems it appears in while studying Celtic and Nordic Mythology at the University of Michigan. Being able to close read and understand literary references are skills I’ve developed over decades, but I didn’t think I was going to get to use them while sitting on the couch watching a Marvel show on Disney+.

But let’s back up for a second. How did we get here?

Read on if you don’t mind spoilers. I’m not a super scholar of all things Marvel (that would be Mr. PopPoetry’s domain) but I’ll give it a shot.

Some Background

In Avengers: Endgame (2019), the trickster god steals the tesseract, a magical science-y cube designed to hold the Space Stone, a super powerful energy stone that “predates the universe.” Sure. Stay with me! When he steals the tesseract, he disappears—ostensibly to a new timeline. When we see him again at the outset of Loki (2021), he’s being hauled into the Time Variance Authority (TVA), an agency devoted to protecting “the timeline.” The TVA informs Loki that by stealing the tesseract, he’s become a variant, or a version of himself that exists only in a splintered timeline that has strayed away from the main or “Sacred” timeline. He also learns that there are now more Loki variants in other splintered timelines, and some of them are doing Very Bad Things. He’s then presented with a choice: help the TVA hunt his variants, or be snuffed out of existence right then and there.

Loki chooses the former, but things aren’t so simple. Madness ensues, and to the surprise of no one, the Sacred Timeline ends up not-so-sacred anymore when a multiverse of timelines is created due to the events of Loki Season One. (Is it Loki’s fault? I’ll give you one guess.) Those same multiverses risk annihilation in Season Two, but Loki finally has an iota of character development when he realizes what he must do to save them: sacrifice himself to save his friends (and, you know, the world… or more properly, the worlds).

Once he understands that he must sacrifice himself to save those he loves, Loki fashions a tree from all the timelines he’s protecting from his lonely throne floating out there in space-time. Loki, Thor, and Co. are superheroes drawn from Norse gods, and so when we see the tree, we understand that Loki is living out his destiny and shaping time into a form he is familiar with: the World Tree.

It’s pretty cool. But this is only one of the two important poetic references in this very literary episode: one older and one much newer.

The Poetic Edda (13th Century)

The Poetic Edda is a collection of Old Norse narrative poems written by an anonymous source or sources. Central to our understanding of Scandinavian mythology, these poems have been deeply inspirational to countless other writers and artists throughout time, including Tolkien, Borges, Pound, and apparently Eric Martin: Executive Producer and lead writer of Loki Season Two and the brains behind its “Glorious Purpose” episode.

How do I know? Easy: Yggdrasil.

As a writer in Thor’s zip code in the Marvel universe, you’ve gotta know your stuff. Thor—and by extension, Loki—are Marvel characters based on much, much older source material, as opposed to Iron Man, whose mythos begins in 1963. There is much to be said about superheroes and superhero comics and films and their relationship to mythology, ancient gods, and storytelling throughout time, but with the Thor franchise and its branches, it’s right there front and center. And largely, this stuff was codified in The Poetic Edda. The writers are doing their Norse mythology homework, here.

Martin has his head screwed on quite well when it comes to writing genre:

You must track the emotional story first… audiences will forgive you if they lose a little bit of the time travel logic there as long as they understand the emotional logic. I don’t want to ever lose the emotional logic of the characters. Right? The human story is the important thing and don’t want to lose focus with that. I wanted to use the time travel as a dramatic device, but I didn’t want it to just overwhelm the story. So how can we keep this as simple and intuitive as possible?

I look at the time travel stuff as like, this is a toolbox that we can go into, and when we have a story thing where our characters can use it… I’m never trying to write time travel. I’m never trying to force it. It is just part of the toolbox.

As is the case with the time travel flavor of Loki, the Norse mythology flavor is ultimately just a “toolbox” item that Martin hopes to use to service the overall “emotional story,” and that’s a smart move. What separates “good genre” from “meh genre”—and by “genre” I mean media (here, films) that conform to certain conventions (think horror, action, sci-fi)—is the willingness to let the conventional aspects take a backseat to the emotional stakes between characters. And Loki largely succeeds by this metric.

But if the Poetic Edda inspired Stan Lee in creating Loki, it’s a different work of poetry that inspired actor Tom Hiddleston as he performed the role.

T. S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding” (1943)

Loki also centers on an antagonist referred to as He Who Remains, a.k.a. Kang the Conqueror. He Who Remains is a scientist from the 31st century who discovered the multiverse and other variants of himself in other timelines. The Kang variants shared their knowledge, but some viewed the presence of other timelines as potential places (times?) to rule over and exploit. A multiversal war began and the original Kang attempted to control the situation by denoting one timeline in particular as a “Sacred” one and setting up the Time Variance Authority to protect it. He installed himself at “the end of time” in a citadel from which he could watch over things. But after eons of this, he grew tired and sought a successor for this thankless job.

Enter Loki, who categorically Does Not Want this job.

However, He Who Remains slowly shows him that it is inevitable. During their conversation in Episode 6, Loki realizes that what’s about to happen to him has already happened and will always happen. He says “We die with the dying… we’re born with the dead.”

And that, my friends, is a quote from T. S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding” from Four Quartets.

Watch the clip above to hear it and listen to ScreenCrush’s Ryan Arey discuss the poem (!) and its relationship to the show. Watching MCU nerds go insane with close reads of none other than Thomas Stearns Eliot is a truly bizarre experience. Is this what it was like when some of the first humans watched other humans discover fire?

The best part is that it wasn’t the writers, but instead actor Tom Hiddleston who nudged the poet into the world of Loki. In an interview with ScreenRant, in addition to revealing how the Eliot reference got into the script, Hiddleston also revealed just how well-read he is:

…Something I talked very early on to Eric Martin about, and Kevin Wright, our producer, was the Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot, which is, I think, one of the most extraordinary pieces of writing in English literature about... Well, it’s just an extraordinary piece of writing in its own right, but it happens to be about time and reality and the past and confronting the past in order to live in the present and move into the future and his ideas of meaning and purpose. And Eliot wrote it in the wake of the Second World War, I think as a way to try and make sense of that collective suffering.

I know Taylor Swift kicked him to the curb, but damn if it isn’t refreshing (and kind of hot?) to hear an actor talking about Modernist poetry like this.

Four Quartets is about several things, but the section Hiddleston quotes on camera is a poem/section called “Little Gidding,” which deals heavily with expansive understandings of time and fate and the limitations of human endeavors. Here’s a relevant section from the poem surrounding the lines that Hiddleston quotes:

What we call the beginning is often the end And to make an end is to make a beginning. The end is where we start from... Every phrase and every sentence is an end and a beginning, Every poem an epitaph. And any action Is a step to the block, to the fire, down the sea’s throat Or to an illegible stone: and that is where we start. We die with the dying: See, they depart, and we go with them. We are born with the dead: See, they return, and bring us with them. The moment of the rose and the moment of the yew-tree Are of equal duration... We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time...

The poem demonstrates an almost science fiction-esque understanding of time that feels like it’s cribbed from quantum physics. But my desire to praise the poem and Eliot as a poet more generally is tempered by the fact that he was an antisemite, so jot that down.

In this time, we need more poetry, more art, and most importantly, more deep thought. I like to see Martin, Hiddleston, Arey, and others doing that kind of deep thinking as they create and consume media. But one of the most important functions of art is that it makes us feel and grows our empathy. For Loki, discovering empathy allows him to save whole timelines full of lives. For us, empathy is how we combat hatred and prejudice and how we stop genocide.

Take a page from Eric Martin: Don’t lose track of the emotional story of life here on earth in favor of its made-up conventions. People matter most: all of them.

Related

Superheros Spouting Poetry: You Love to See It

I think a lot about Martin Scorcese’s often-cited comment that Marvel movies are “not cinema.” In a 2019 interview with Empire, the famous director likened the MCU to a “theme park” designed to appeal to the masses—a categorically different imperative than the films he makes …

This X-Men Character's Love of Poetry Got Left Out of the Film Franchise

As Derrick Austin noted in his PopPoetry interview, X-Men: The Animated Series (1992–1997) introduced countless 90s kids to poetry more than once. How did the show work poetry into superhero situations? Through the extraordinary character of Beast, of course.