Happy Mother's Day from the Horrifying Poet-Husband of Darren Aronofsky's Mother!

Gendered Creative Labor and the Narcissist Male Poet

PopPoetry is poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post! Come in: I love having company. Right? Right?

Happy Mother’s Day, darling! I got you a tiny picture of my face that you can clutch feverishly by candlelight. Do you like it?

You’ve made this house a home. I appreciate every detail you’ve added. Is that a load-bearing sink, by chance? Say, if some of my friends wanted to fornicate on it… think it’d hold? Nevermind. I made you breakfast in bed!

Like Gaia herself, you are resplendent in your womanly fullness. I can’t wait to introduce our child to my legions of followers… I mean, I can’t wait to kiss his fat widdle feet!

Happy Mother’s Day!

Sure, why not celebrate Mother’s Day in the United States by taking a look at a disturbing psychological horror film featuring a mother-to-be and an egomaniac poet?

It was fun to make light of the 2017 horror film Mother! above, but in reality, Aronofsky’s picture is incredibly disturbing and violent. I’ll never forget watching it in theaters (remember those?) with my friend Trista. Once the film started, it gripped us, squeezing tighter and tighter until we were both literally curled in the fetal position in our respective seats, which I think is the desired effect. It shook me for weeks. It shakes me now.

I don’t describe the most violent aspects of the film here, so you’re safe to read on. But if you choose to watch, do know that you’re in for physical horror as well as the horrors of emotional and psychological abuse.

A histrionic though not inaccurate portrait of what it can be like to be a woman—used, plundered, and then cast aside—the film is also accurate in its portrayal of abusive male narcissism and gaslighting. And the abusive man in this film is, as it happens, a poet.

Two Creatives

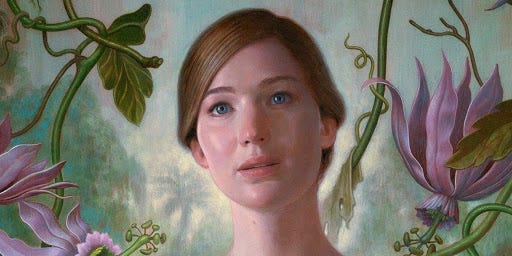

Referred to only as “Him,” the husband (Javier Bardem) and wife (Jennifer Lawrence, or “Mother”) live alone in a large, secluded house. By naming the characters in such basic ways, Aronofsky invites us to think of the film as an allegory. Much has been written on the subject of the various allegorical moves the film makes (many of them biblical or ecological).

But if we also understand the film as one about creativity, we’re able to grasp a chilling argument about the gendered expression of creative work (particularly within relationships where both partners are creatives).

In Aronofsky’s beautiful and bonkers film, Him is a famous poet, but Mother is an artist herself as well: from the early scene where we watch her mix paint and daub it on a wall in her home with precision and care, we become aware of her artist’s eye. She can feel the soul, the beating heart of the house as she works. Sunk into her creativity, she is at peace.

Dismissed as mere “setting” for her marriage, the gorgeous house she gut-renovated is one of Mother’s two major creations. But her creative energies are buried beneath the mountain of work that keeps being created for her as guests show up and destroy her home: her work of art.

The Poet: Him

The premise of the film is that one night, a fan (Ed Harris, known as “Man”) turns up on the couple’s porch: his dying wish is to meet the illustrious poet. Soon, the man’s wife, known as “Woman,” (Michelle Pfeiffer), appears as well, followed by their sons. The sons fight brutally, and one is killed (Cain and Abel, anyone?) Him allows the family to hold a funeral for the young man in their home, which quickly turns into a raucous party and gets out of hand.

Throughout this period, Mother begs Him to stop inviting strangers into the home, asks them to leave, and tries to protect the home she has painstakingly created from the destruction of interlopers. The poet does not intervene, help, or even hear her, and dismisses her concerns as stinginess and materialism.

Eventually, she comes to a breaking point.

The poet’s cultish aura turns the wake into a wild, idolatrous party. Him eats up the attention and overflow of emotion, while Mother understandably dissolves. Once the guests have left, Mother and Him fight, which turns into sex (to which she does not consent at first).

In a moment of magical realism, Mother becomes aware that she is pregnant, and this collaborative act of creation inspires the poet to break through the ice of his writer’s block. While Mother is left to clean up the destruction of the revelers’ apocalyptic partying, the poet retreats to his desk to write. That’s right: he creates, she cleans.

The poet says it’s everyone’s house!

We jump forward in time, and Mother is now heavily pregnant. She feels the child, her creation, kicking, and rushes to tell Him. But Him is absorbed by his own creative work, as he has finished the poetry he has been toiling on for so long.

He gives it to Mother, who reads it and literally weeps. Suddenly, the phone rings, and the idyll is broken. It’s the poet’s publisher, who loves the new work. What Mother thought was an intimate moment between the two of them clearly was not. He has already shown the work to others.

To celebrate his creative success, Mother prepares a lavish dinner for the couple, but a fan once again interrupts the proceedings. Several more fans show up, clamoring for the poet’s attention. “Just keep everything warm,” he tells her as he goes to the porch to see his adoring horde. And that’s Mother’s job, isn’t it? To wait. To serve. To remain in perpetual, ready stasis, ignoring her own creative impulses. Every time she has an opportunity to focus on her own acts of creation, she’s ignored and thwarted. Her job is to bolster him.

The zealots infiltrate the home, begin to celebrate raucously, and then things take a sinister turn. Hundreds of people flock to the house, break up the private dinner, and break up the house. When Mother begs Him to see that his fans are destroying her creation, he says “Those are just things. They can be replaced.” When she tells a fan that this is her house and asks him to leave, he says, “The poet says it’s everyone’s house!”

In the remainder of the film, Mother’s Gaia-esque creations—the house and her child—succumb to the destruction wrought by the poet’s ruthless self-obsession.

I want to tell myself that there is no truth to the caricature of the male poet of Mother! But I can’t.

My ex routinely invited people who were not known to me into our home without asking me because they were writers with whom he wanted to associate. So calculated were his moves that every interaction he had with other people was designed, I see now, to collect other writers and acolytes like Pokémon.

He convinced me that my work did not have meaning.

I read and edited much of his work, but when it came time for reciprocity, he lied about having read my manuscript. He convinced me that my work did not have meaning while fawning over the work of every other writer he read and met. Once he determined that there was nothing left I could give him, he discarded me and found others, plural, to take my place. And when I told him how badly he had treated me, he looked me in the eye and said, I am a very loving person.

His creativity, in short, was exploitative and emotionally abusive. Rather than a generous, generative practice, abusive narcissism drove his professional and personal activities. Nothing was more sacred than his pursuit of recognition. My own acts of creation were lesser-than, from my writing to the creation and maintenance of the home that we shared.

This is the creativity of Him.

I see Him in him. There are many like Him. Just ask any woman writer that you know: she’ll have a list. Or any woman.

When people are reduced to categories, they become expendable.

Mother’s function in the film is to tend Him’s needs and moods like a churlish garden. He spends most of the film not writing. And as much as writers know that not writing is part of writing, Him is tortured. There is no play in Him’s work, no joy or exploration. He simply applies maximum pressure to the task of creating a masterpiece, and he uses Mother as his muse. And playing the muse, we see, means that you are only one of a category, a type of woman rather than an actual woman. And when people are reduced to categories, they become expendable.

Creativity, Labor, and the Cult of Personality

Part of me wants to laugh at the film’s central premise: a poet so beloved and well-known that his acolytes flock to his home in droves and beg to be anointed? I’m excited if I get a few retweets and $25 when one of my poems is published, and the situation isn’t exactly a mob scene for even the most famous living poets on earth.

Poetry is incredibly powerful and potent, but poets themselves often do not wield the power of lauded novelists, nonfiction writers, screenwriters, or other, more visible wielders of the pen.

As Maggie Smith noted in her recent interview with me, poetry can feel like a small club or “treehouse gang” of artists, which has many good and some troubling realities. It’s difficult to imagine that any poet alive could inspire this kind of devotion not only because of poetry’s relative obscurity, but also because poets tend to be skeptical of idolatry and cultish devotion of all kinds. Any good poet, you might say, would shun that level of adulation.

I’ve seen it happen myself in real-time at writer’s conventions and readings: a young poet grovels toward an older, venerated poet and burbles up many wonderful words of devotion only to have the older poet brush them off gently, waving away such effusive praise.

The truth is that the corrupting forces of toxic masculinity, male privilege, and good-old-fashioned gaslighting and abuse are pure realism.

In some ways, Mother! comes across as the ultimate fantasy, then. But the truth is that the corrupting forces of toxic masculinity, male privilege, and good-old-fashioned gaslighting and abuse are pure realism.

In our time, countless men lauded for their creative work have routinely been revealed as abusers and narcissists who were able to create because they stepped on others. And the idea of “genius” is so firmly welded to the idea of masculinity that it seems unlikely, at times, to ever be fully pried away. We know that women still bear the brunt of housework and childcare responsibilities in addition to the mental load of the household, and the pandemic has only widened the gap.

The question of who gets to be a creative is not merely an emotional or intellectual one. In reality, it’s also an economic and political question. The Mother of Mother! learns that her partner’s desire to achieve fame means that her own creations will be destroyed in service of his Dionysian vision of the world.

The idea that a poet could create a violent, adoring mob somewhat stretches the imagination, but the idea that he could gaslight and destroy the creations and creative spirit of his partner? That’s much more real. Though it certainly takes some ego to create at all, if our creativity isn’t coming from a position of expansiveness and generosity, isn’t it just destruction?

Mother’s Day can be a tough holiday for many, so take care of yourselves and those you love this weekend. I’ll see you again soon.

P. S.

I was so pleased to be interviewed by Foley Schuler on Blue Lake Public Radio at the tail-end of National Poetry Month. You can listen to our conversation here.

I’m not the only one loudly championing the inclusion of the work of living writers in our lives and in our classrooms.

But poetry doesn’t have to live inside a classroom. It has applications everywhere, including in medicine.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it, subscribing, or sending it to a friend. Or better yet, all three!