Stay Gold: The Post-Postmodern Life of Frost's "Nothing Gold Can Stay"

From a novel to the screen to a song to video games to t-shirts and wall hangings and more, Robert Frost's dictum to "Stay Gold" has had incredible staying power.

Timeline

1923: Robert Frost’s poem, “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” is published in The Yale Review

1967: S. E. Hinton publishes The Outsiders, a coming-of-age novel, with Viking Press at the age of 18

1983: The motion picture adaptation of The Outsiders, directed by Francis Ford Coppola and starring C. Thomas Howell, Matt Dillon, Ralph Macchio, Patrick Swayze, Rob Lowe, Tom Cruise, and Emilio Estevez, arrives in theaters

1990: Christopher Sergel adapts Hinton’s novel into a full-length stage play. A television miniseries of The Outsiders directed by Coppola also airs on Fox

1997: The Get Up Kids release their song, “Stay Gold, Ponyboy,” on their debut album Four Minute Mile

2006: Rockstar releases Bully, a role-playing video game about a school divided into factions that include the Greasers and the Preppies—at one point, a main character uses the phrase “Heads up, Ponyboy”

2021: An Etsy search for “Stay Gold, Ponyboy” returns 574 t-shirts, stickers, wall hangings, hats, necklaces, and other ephemera available for purchase

Stay Gold

Stay gold, Ponyboy. Stay gold. Even if you’ve never read S. E. Hinton’s coming-of-age novel The Outsiders or seen the 1980s film adaptation, it’s likely that you know this phrase because it floats around in the pop culture airwaves.

This quote from the novel—and later, the film—is inspired by a Robert Frost poem published in the first part of the 20th century. “Nothing Gold Can Stay” might have been a part of your high school English curriculum: Frost is a mainstay of such reading lists for reasons that are both benign and nefarious.

As pervasive as his texts are in classrooms, we don’t tend to teach Frost all that well, either. In his article, “When Teachers Talk to Students About the Poetry of Robert Frost,”1 James B. Kelley writes:

…teachers rarely discuss the contexts in which Frost’s poems were produced or continue to circulate and, particularly when talking about the themes and messages in the poems, often do not pay close attention to the language in the poems. Frost’s poems are frequently reduced to timeless and unambiguous statements.

The most regularly contextualized poem in the working sample is “Nothing Gold Can Stay.” Five of the six teachers answering questions2 on the poem discuss its appearance and function in the novel The Outsiders. For Frost’s poems in general, however, there is little discussion of context.

What’s interesting is that in the book and the film adaptation, the boys engage in acts of interpretation themselves when they confront the poem. At first, they seem to understand the idea that “nothing gold can stay.” But the famous exhortation to “stay gold” is actually a youthful corruption of the poem’s meaning: an act of wishful thinking that has, interestingly enough, inspired generations.

“Nothing Gold Can Stay”

Frost’s “Nothing Gold Can Stay” is an observational poem about nature that can be understood to have a deeper meaning about value, time, life, and death. Yeah: we’re going to close read this poem. It’s only 8 lines long. We’ve been through worse!

Nothing Gold Can Stay

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.—ROBERT FROST

Let’s look at it line by line.

Nature’s first green is gold,

In this line, “gold” can mean “valuable,” as in the first green shoots of plants are the most important parts of nature. The beginning of things is magical and meaningful. I also see a bit of science, here: nature’s first “green” or life lies in the sun, the “gold” mentioned in the line. This creates a nice complement to the image of the sun we get in line 7.

Her hardest hue to hold.

The beginning of things doesn’t last forever, in nature or anywhere else—“hardest” here means “difficult.” It’s hard to hold onto the beginning: impossible, even. And if we’re reading “gold” as sunlight, the transience of the light is moving here, too. Plants aren’t able to “hold” the light they receive forever, and neither can we.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

“Her” refers to nature in this line, as well. This intricate image of five spare words refers to the way that new, budding leaves often take the appearance of flowers as they unfurl. Frost here compares the “early” or new leaf to a flower, which we understand to be an image of beauty.

But only so an hour.

Frost reminds us that this beautiful early leaf-flower is a very, very brief stage in the life cycle of a plant. This line is a restatement of the themes already established in lines 1-2, and reminds us that the beautiful, the vital, and the new are short-lived.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

After the leaves bud, they fall. Year after year, a crop of leaves on a tree grows, dies, and is replaced by new leaves. Each leaf “subsides” or falls down before other leaves replace it. This line makes us think of the sequencing of events in nature as well as their regularity.

So Eden sank to grief,

Here is the poem’s first true imaginative leap. In line 8, we are transported out of the rural natural landscape and into the realm of the spiritual. By comparing the nature outside our windows to the biblical garden of Eden, Frost Not even paradise could last, Frost seems to say.

So dawn goes down to day.

The image of the sun returns here once again. Just as every dawn, we know, resolves into a day before repeating once again overnight, there is a cycle to all things in nature. The ending is woven into the beginning.

Nothing gold can stay.

The final line gives the poem its title and creates a sense of symmetry in the overall piece, as it begins and ends the same way, further reinforcing Frost’s ideas in this marriage of form (the structure of the poem) and content (what it says). All things that begin must end, a truth that we see reflected in nature.

Stay PoMo, Ponyboy

The use of “Nothing Gold Can Stay” in The Outsiders involves a kind of reversal of Frost’s intended meaning, and functions in a context outside of the poem’s original one. Johnny tells Ponyboy to “Stay gold.” Frost tells us that “Nothing gold can stay.” Johnny is asking Ponyboy to do something they both know he can’t do. Or rather, Ponyboy may be able to “Stay gold” for a while or for as long as he can, but ultimately, as the poem again reminds us, leaf will subside to leaf. Ponyboy won’t stay gold.

He could only “Stay gold” if we willfully misunderstand Frost’s meaning. The poem is asking us to embrace the transience of life and to see both beginnings and endings as holy; The Outsiders assigns a valuation to staying “gold,” which they interpret to mean being young and pure and full of belief and goodness.

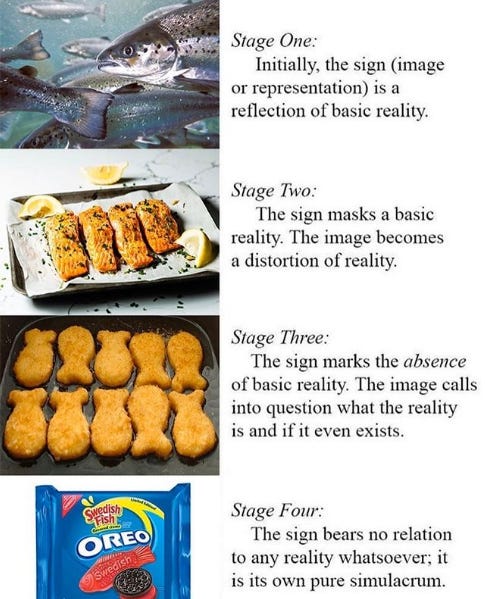

Sometimes when I think about the phrase “Stay Gold” and the Frost poem it sprang from, I think about this meme:

The text of the meme is lifted from Jean Baudrillard’s “The Precession of Simulacra.” One of Baudrillard’s beliefs was not that signs bear no resemblance to reality, but that a shared understanding of reality has no real bearing on how we live our lives.

As we move from Frost’s poem to Hinton’s integration of the poem into her text to a film adaptation of the novel to a stupid piece of painted wood with the words “STAY GOLD” laser cut out of it that is definitely not hanging on my wall as I write this, we arrive at a phrase which “bears no relation to any reality whatsoever,” in a way. When we now exhort someone to “stay gold” absent the original context of Frost’s poem, we’re engaging a deep distortion of the original text. We are several cuils away from reality.

In other words, we’re living in Baudrillard’s hypperreality and loving every second of it. I don’t lament this procession (or precession) so much as marvel at it, pleased and shocked that a poem written in 1923—itself a mere sign that gestures weakly toward the “reality” of the natural world—is at its core.

The way the poem, the novel, and the film have worked together to spawn everything from video games to fridge magnets to stage plays is astounding, and is proof, I’d argue, that the act of interpreting art can sometimes be as generative as making art itself.

Related

Kelley, James B. “When Teachers Talk to Students About the Poetry of Robert Frost.” The Robert Frost Review No. 21 (Fall 2011), pp. 24-40 (17 pages) Published by: Robert Frost Society.

in the online forum that Kelley was scrutinizing

This poem & saying come to mind when looking at "The Golden Boy of Pye Corner" in London. Most people know that Pudding Lane was where the Great Fire of London started. Few know where it stopped. A rather seedy corner of medieval London, at the corner of Cock Lane and Giltspur Street.

Cock Lane was one of the few places where brothels were legal. Its neighbour Giltspur Street is the place where the Lord Mayor of London stabbed Wat Tyler.

At the corner of these two streets stood ‘The Fortune of War’ pub, an unsavoury drinking hole where during the early 1800’s body-snatched corpses were held until the surgeons at the nearby Saint Bartholomew’s picked them up.

The inscription on the memorial states:

"This Boy is in Memory put up for the late Fire of London

Occasion’d by the Sin of Gluttony."