All That Glitters: Is This the Best Book of Poetry Ever Written by a Celebrity?

That might depend on your definition of "celebrity."

You’re reading All That Glitters: (Re)appraisals of musicians, actors, and other culture-makers who have published poetry. All That Glitters is a semi-regular feature of PopPoetry, a poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here or check out the archive to see other TV shows, movies, and films whose intersections with poetry I’ve covered. Like what you read? Subscribe so you won’t miss a post!

Actual Celebrity

Why haven’t I written about the brilliant 1999 collection of poetry by Silver Jews frontman David Berman until now? Probably because it feels like cheating.

The Silver Jews—a band comprised of Berman, Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich, and, later, Cassie Berman—are well-known to indie rock fans but don’t have household name recognition. Founded in 1989, the Silver Jews made five albums together through 2009 when the group disbanded. Berman later resurfaced with new music under the name Purple Mountains in 2019, just months before he died of suicide. His music, and particularly his words, have attained a kind of cult following.

Berman’s songwriting is also so rich that his words feel poetic as-is without a book to his credit. Take, for example, the opening lyrics of “Random Rules”:

In 1984 I was hospitalized for approaching perfection Slowly screwing my way across Europe, they had to make a correction Broken and smokin' where the infrared deer plunge in the digital snake I tell you, they make it so you can't shake hands when they make your hands shake

Berman is often verbose like this, and to great effect, but he also has sparer lyrics that still know how to throw a punch, like this one from “Trains Across the Sea”:

Half hours on earth What are they worth? I don't know In 27 years I've drunk fifty thousand beers And they just wash against me Like the sea into a pier...

And so, a book of poetry by a guy like this feels much less like a wacky one-off from Billy Corgan or Jimmy Stewart, a book of poems written because one can, because one is already famous and why the hell not? Berman had published a few standalone poems and was urged by a friend to complete a book, which he did. That book is Actual Air, published by Open City Books just before the turn of the millennium.

Berman’s friends and bandmates report that he had an obsessive approach to writing lyrics and sometimes found himself hung up on a single line for weeks or even months. Extreme focus on the exact right word or line is not a songwriting tic one finds everywhere: This, my friends, is a habit of poets or the poetically inclined.

While many books of poetry written by celebrities fail to demonstrate any of the charms or strengths that their authors displayed in other art forms, Berman’s book takes his rich lyricism to new heights, leaving us with a dazzling collection of deftly written poems about life on earth in all of its perfunctory disappointments that isn’t just for the indie rock crowd: it is, as James Tate wrote, “a book for everyone.” And in terms of its authorship by someone who is famous for his work in a different art form at the time of publication (i.e., a celebrity), it just might be the best book of its kind so far.

Actual Poetry

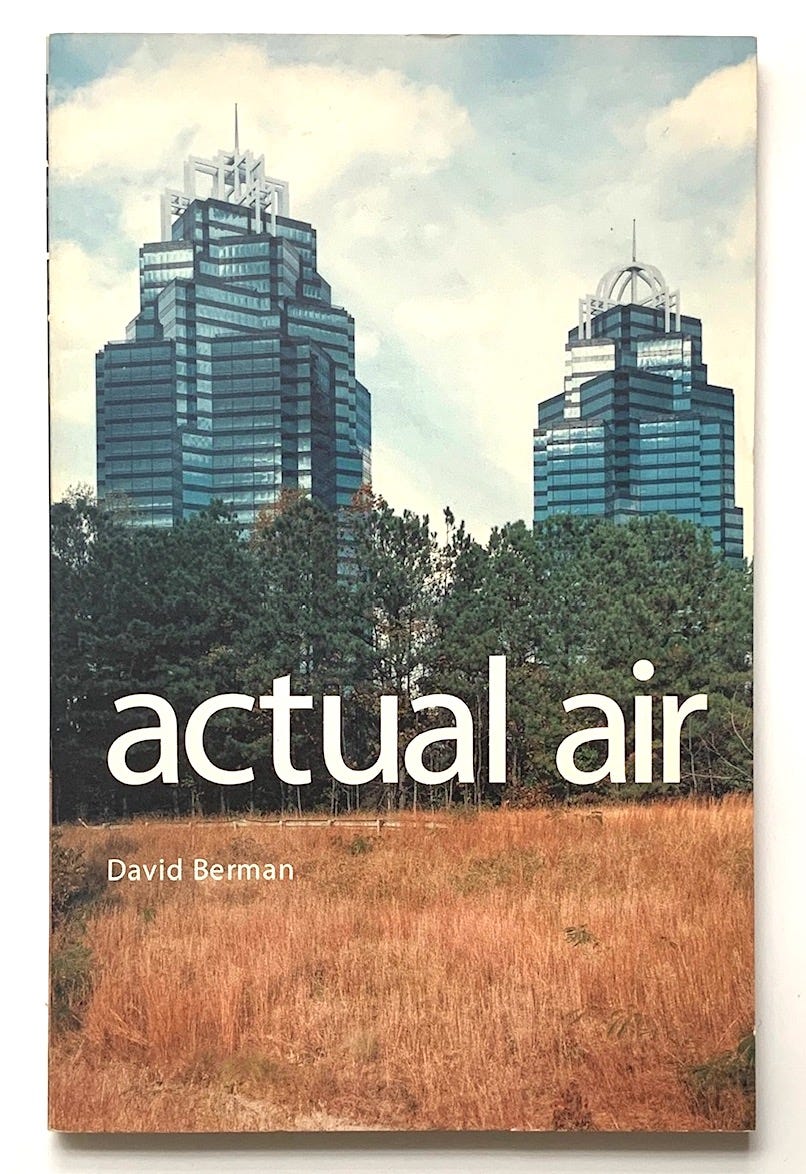

I first came across Actual Air in college, around 2005. Some folks in my poetry workshops were passing it around, asking have you read this shit? It’s unreal. I had to have my own copy, and glad I am that I purchased it when I did. The original paperback editions, like the one pictured below, are now much harder to find than the 2019 hardcover reissued for the book’s 20th anniversary.

The iconic cover of this edition features a photograph by Roe Etheridge that could be anywhere but also reads as deeply American (it is: it’s outside Atlanta). The focus on the juxtaposition between the city sprawl and the feeble natural landscape heavily informs Berman’s poems. In his excellent essay on Etheridge, Berman and “municipal feeling,” Harris Feinsod writes,

Late in his life, Berman declared that he thought and wrote in “fragments” as a definite “product of a postmodern era,” but postmodernism here might best be understood in its core sense of a spatial and architectural politics…

he offered fragmentary observations of getting along in a sprawled edge city world, “[c]ast as we are into this underimagined place.” His fragmentary art of postmodern aphorism took the edge city's psychogeographical measures of spatial discontinuity, confronting a history with material coordinates in real estate development, privatization, and municipal nostalgia…

Actual Air is also a book about astonishment—but not your garden-variety “wow.” The speaker of these poems is alternately astonished by his ability to find and make meaning in a degraded world and astonished by the mundanity of “the way things work.”

In “Governors on Sominex,” Berman writes, “There were no new ways to understand the world, / only new days to set our understandings against.” In his characteristic aphoristic style, Berman might just have summed up the entire book in this moment.

Actual Air was very well received, and rightly so, by the poetry community at large upon its publication. The book received accolades from The New York Times, Publisher’s Weekly, The New Yorker, and, importantly, working poets in the literary tradition, including Billy Collins and James Tate. Charles Wright and Dara Wier also receive nods in the book’s acknowledgments.

But whether you set store by the opinions of these folks or not, the blend of bewilderment and beauty that Berman offers in his strange yet strangely warm poems is undeniable. Again and again his words surprise and delight. Consider this excerpt,

I put my book down and come to the window where curtains are fastened to the sides so it is like looking out at the world through the back of a teenage girl's head and my signature is drawn in magic marker on the lower right hand corner of the window so when something passes in the dark it's captured for a moment inside my work. —from "World: Series"

or this one:

because this world is 66% Then and 33% Now, and if you wake up thinking “feeling is a skill now” or “even this glass of water seems complicated now” and a phrase from a men’s magazine (like single-district cognac) rings and rings in your neck, then let the consequent misunderstandings (let the changer love the changed) wobble on heartbreakingly nu legs into this street-legal nonfiction, into this good world, this warm place that I love with all my heart, anti-showmanship, anti-showmanship, anti-showmanship. —from "Cassette County"

Actual Air documents a sensitive human being trying not to see death and disappointment in America’s fractured landscapes and consciousness in favor of noticing the small ways in which things could be provisionally good instead.

Actual Precision

This excerpt from “Narrated by a Committee” shows off Berman’s assured voice and keen eye. His sense of image and detail, in addition to his attention to language, are on full display here:

The enamelled moon rode over the long cool world as we stepped outside to get some air. Birds from other area codes sang parts of songs out in the park, the light pulse of the seminary faded in the wax trees, as we strolled around talking about the burden of inheritance tax and the elegance of watering cans.

Time and time again, the question of “relatability” rears its head in poetry communities and classrooms: novice readers and writers mistakenly assume that generalizing will allow them to “speak to everyone.” Time and again they are wrong. It is this kind of specific detail that makes poetry come alive, that telegraphs the existence of an actual human subjectivity from behind the page.

In the age of A.I. and nauseating discussions about machine-produced language that we are, sadly, only at the beginning of, it is poetry like this that we should lift up as an example of what the art form can do, not the poems that fill up Instagram with their received language and platitudes.

Bob Dylan made headlines when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016 and ignited discussions about the relationship of songwriting to poetry, but for me and perhaps for many in my generation, it is David Berman who best exemplifies the ways in which songwriting can flower forth into poetry, which can meditate longer, and even more creatively, on what it means to be human—to be mortal—in this strange country. I don’t know if we’ll ever see a book like this again, and we certainly won’t see a talent like Berman: a truly one of a kind writer whose “celebrity” was the least interesting thing about him.

Related

All That Glitters: Megan Fox's Book of Poems Will Make You Wonder Who They're About—and That's the Problem

I desperately wanted Pretty Boys Are Poisonous—Megan Fox’s first book of poetry—to disarm me, to flatten me with an unexpectedly assured voice that could speak from the other side of beauty and celebrity and Hollywood to show me something new. And while Fox does write about what’s behind her glittering facade, what’s there is sadly quotidian in both its subject matter and its language.

All That Glitters: Is Bob Odenkirk's Zilot Generation Alpha's Where the Sidewalk Ends?

You’re reading PopPoetry’s 200th post! Click here to check out the searchable archive of past posts. All That Glitters is a semi-regular feature of PopPoetry that offers (re)appraisals of musicians, actors, and other culture-makers who have written and/or published poetry. Check out more while you visit the archive, and subscribe so you don’t miss a post!

All That Glitters: We've Ruined Drake

When Drake’s seventh studio album came out in 2022, the surprise release felt as room-temperature as the air leaking out of a dead balloon. The title? Honestly, Nevermind. It was, yeah—deflating. The refusal to title the album in a serious way and eschew the titling process altogether felt less like hipsterism and more like apathy. But Aubrey could easi…

Thank you for this piece. I am going to take a deep dive into his writings.