MTV's Daria, "The Greasy Fry," and The Commodification of the Beats

The story of the anticapitalist Beat poets' commercialization as harmless, laughable "Beatniks" is at the heart of Quinn Morgendorffer's poet performance on the cult animated show.

Do you value the work that goes into this newsletter each and every week?

Consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support makes this work possible, and in addition to excellent karma, subscribers get access to special writing prompts, Friday link round-ups, and more. I’d be honored to have you aboard this weird little ship I’m sailing into the seas of culture.

I’m fascinated by pop culture depictions of poets.

Sometimes they’re shouting nonsensical phrases into a microphone in a send-up of slam poets. Sometimes they’re writers in other genres who are pressed into service for special occasions. At other times, they’re moody, wandering loners who live inside their notebooks.

There are wisps and whispers of accuracy in each of these depictions, but overall their assumptions about who poets are—and by extension, about what poetry is—are oversimplified. Yes, slam poets can be animated, but to suggest that their delivery is about style over substance is false and sometimes even rooted in racism. The idea that all writers can write poetry is similarly incorrect (ask any novelist). And while many of us keep notebooks and enjoy observing the world around us, the notion that poets are hermetic weirdos can turn people off the art form, which is a big old bummer.

But perhaps the most trenchant stereotype of who poets are is the one that dwells on their surface-level aesthetics: poets wear all black, don berets, and maybe even play the bongos. Don’t they?

No, they don’t. Did they ever? Where did this image come from?

Beats & Beatniks

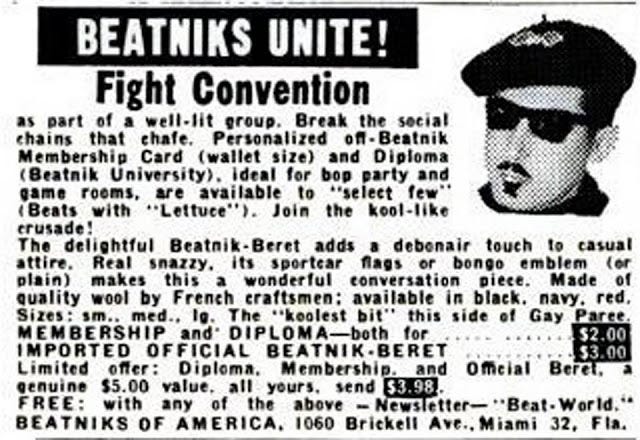

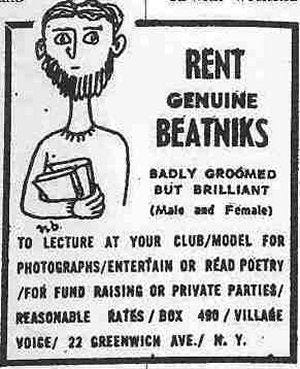

Much to their chagrin, the Beat poets active in the 1950s—who were rebelling against the confinements of mainstream culture—ended up being devoured by the very capitalist machine they sought to escape. Beat fashion and speech affectations bloomed into stereotypes while the Beats’ politics and dissatisfaction with mainstream culture withered. In short, popular culture retained their style but discarded their substance with alarming speed.

In “Rumblings of Discontent: American Popular Culture and its Response to the Beat Generation, 1957-1960,” Stephen Petrus writes:

Many entrepreneurs, seeking financial gains, took advantage of the popularity of the bohemians… Beatnik clothing also turned into a hot commodity. The Young Individualist Shop, a bou tique in Manhattan on Fifth Avenue, noted the New York Times, sold a variety of fake furs and a black wool dress with a sleeveless tunic of mock leopard designed to appeal to the “on-beat chicknik.” College stores throughout the nation, as shown in Life, offered loose sweaters, tight black trousers, skirts, and leotards items that beat chicks consider “the end.” And department stores, wrote Lloyd Zimpel, advertised beatnik kits, complete with the standard dark glasses, sandals, beret, and even a phony beard!

The Beat Generation was thus reduced to the commodified image of the “beatnik,” a term credited to writer Herb Caen who attached the Yiddish -nik suffix, which often denotes someone who does things in a particular way. The beatnik wasn’t just an outfit: he became a staple of popular culture of the time, including on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis and in Popeye cartoons. The beatnik was work-averse, too cool, and spoke in a dialect peppered with “like” and “dig,” terms co-opted from Jazz and other subcultures. Sound familiar? That’s because we’re still not tired of it.

In a letter to the editor of the New York Times Book Review in 1959, Allen Ginsberg rails against the use of the word “beatnik,” which David Dempsey had used several times to refer to Jack Kerouac or his characters in a review of Kerouac’s Dr. Sax:

But the “beatnik” of mad critics is a piece of their own ignoble poetry. And if “beatniks” and not illuminated Beat poets, overrun this country, they will have been created not by Kerouac, but by industries of mass communication which continue to brainwash Man and insult nobility where it occurs.

Ginsberg signs this missive “Prophetically, Allen Ginsberg.”

It is these “industries of mass communication” that gave us the most deep-seated image of the poet as one who is obsessed with her style over her substance, someone who wears black and dons berets.

Forty years after Caen coined “beatnik,” MTV’s Daria, the Beavis and Butthead spinoff with a now-cult following, gave us Quinn Morgendorffer, the poet.

And what kind of poet do you think she fashioned herself after?

Quinn the Poet

Daria, which ran for an impressive five seasons and two TV films between 1997 and 2002, was a cultural touchstone for tons of smart-alecky 90s kids like me. If you know the show, you would expect hyper-intelligent and self-aware Daria herself to be the poet of the family, since her sister Quinn is a stereotype of every self-obsessed magazine-reading teen fashionista in training.

But in Season 2, Quinn becomes the smartypants of Lawndale High in Episode 3: “Quinn the Brain.” But interestingly, it isn’t math or science that earns Quinn a reputation as a brainiac: it’s writing. First, a ranting essay about how school is like a prison that Quinn submits in Mr. O’Neill’s English class (we’ll have to return to him at a later date) gains notoriety in the school paper. Then, after Quinn gets over her initial reaction of shock and disgust at being labeled a “brain,” she leans into it in a really weird way.

She starts to re-brand herself as a poet. Her first composition? A poem about a French fry.

The French fry poem has some of the most common poetry stereotype hallmarks—it rhymes and it hints at a depth that it doesn’t actually have. And it’s literally about surface-level appearances:

The greasy fry it cannot lie. It’s truth is written on your thigh.

Quinn is really knocking this poetry thing out of the park. But she doesn’t stop there. She wants to look the part, too, so she starts dressing in an exclusively black wardrobe.

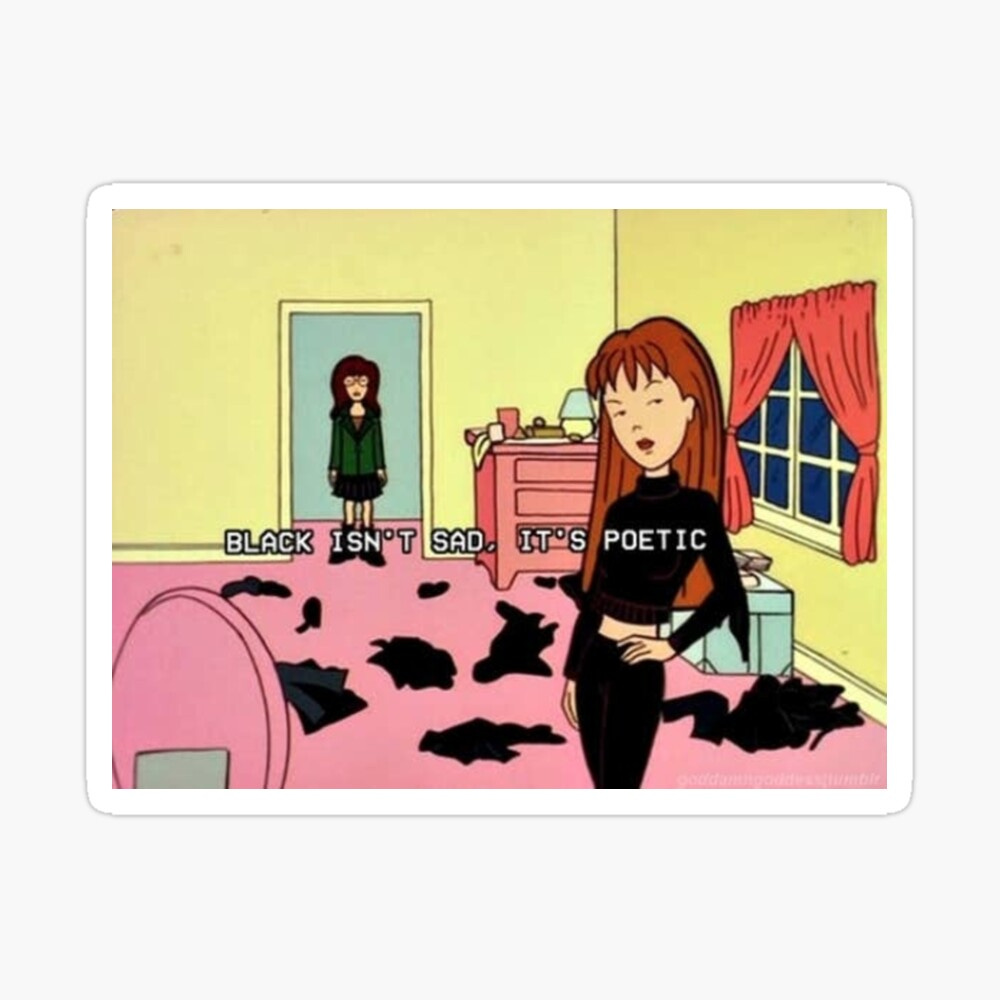

A popular image that has made its way around the internet and even onto t-shirts seems to show Quinn intoning “Black isn’t sad, it’s poetic.” The thing is, Quinn never says this in the episode. But the connection is pretty spot-on, and Quinn’s aesthetic, here, is directly lifted from depictions of Beat poets.

This is probably the most common depiction of who poets are in terms of their wardrobe. Interestingly, in the shots of Quinn dressing like a poet, you can see a black beret sitting jauntily atop her mirror, hanging over but not physically on her head. A little sight gag about how cliché it all is?

“This is how deep people dress,” Quinn tells her sister. She’s certain about how the fashion of poetry works, but less certain about the art form’s mechanics: later, she tells her bevy of male suitors “Yeah, I just found out poems don’t even have to rhyme. How easy is that?!”

The Surface and the Depth

Daria reels from Quinn’s transformation. She’s actually smart, but no one cared about that because she wasn’t hot and popular, like her sister. Daria asks Jane if people only care about brains if you also have “bouncy hair.” It’s a sad scenario: Daria learns that there are other qualities to covet—like intelligence and empathy and humor—but that those qualities are better in conjunction with conventional beauty. She tries to explain how Quinn’s morphing into a brainy poet has upended her understanding of her place in the world:

Let’s say you have an identity you don’t even like. But even though you don’t like this identity, somebody suddenly comes along and steals it from you… you didn’t want this identity, but if they take it away you’ve got nothing.

Her father, Jake, misunderstands, of course, but we get it as viewers. It might even make you think: how important is the author's photo on the back of the book of poetry? Do you feel more inclined to read the book if the person is conventionally attractive? Are intelligence and artistry siloed off from such shallow considerations? Or do we only want to believe that they are?

The episode skillfully moves through the fine contours of this particular problem but ends up stumbling in the last act: Daria is only able to restore balance to her world by turning herself into a “hot” girl and getting dates so that jealous Quinn will go back to her old ways and let Daria be the brain again. Daria applies mascara, wears a midriff top, and bribes Quinn’s would-be boyfriends into pretending to ask her on dates.

Isn’t clever how mainstream society derided and de-fanged a cultural force that was dangerous to its existence?

It’s gross, and the episode ultimately declines to answer the main question it raises: is a brain all that’s required to be a revered intellectual? Or does bouncy hair help? But in the end, it does expose Quinn as a poser who is only into poetry to the extent that it increases her likability. She tries on the “beatnik” costume like so many have only long enough to try to profit from it.

Ginsberg, in his wisdom, was right. Mass culture ground even a literary movement as subversive as the Beats into a pablum, and it did so with shocking speed. What’s captivating is the longevity of this stereotype: from 1958 to 1998, little changed, it seems. Isn’t clever how mainstream society derided and de-fanged a cultural force that was dangerous to its existence?

Where else can we see that happening today? In the mocking of “woke” activists? In the bigoted mischaracterization of drag performers as deviants?

Many of Daria’s viewers were and are savvy enough to see how silly Quinn’s performance as a poet is, but the repetition of the stereotype does have the effect of deepening it, and that matters, both politically and poetically. If we don’t have legitimate models for who poets are, who will our next generation of poets be? If young people can’t picture themselves as poets, how will they travel toward a vision they can’t see?