The Poet Who Wrote Björk's "Sun in My Mouth"

This famous poet's contributions to the Icelandic singer's fourth studio album are much larger than some fans seem to realize.

The Weird Punctuation Guy

E. E. Cummings is a popular guy. Still regularly cited as a favorite among my students 60 years after his death, Cummings’ work pops up in popular culture frequently. For a poet whose work is littered with unusual typographical inventions, dense symbolism, and surreal humor, Cummings’ enduring popularity never ceases to amaze me. As Randall Jarrell once wrote, “No one else has ever made avant-garde, experimental poems so attractive to the general and the special reader.”

His work isn’t always easily quotable, but it’s certainly memorable. Small snippets of Cummings’ poetry have lingered as shorthand for his entire dreamy, erotic, and playful point of view. The phrase “I carry your heart with me,” for example, lends its name to an episode of The Vampire Diaries, gets mentioned in Ray Donovan, is recited in the 2005 film In Her Shoes, and even pops up in a Calvin Klein ad, just to name a few.

On the reverse, Cummings’ lifelong interest in popular culture as a subject in his writing means his work is littered with delightful references to movies, comic strips, and other so-called low-culture items. In short, there’s plenty to say here on PopPoetry about the man known as the second most-read poet in America after Robert Frost at the time of his death.

Cummings isn’t without his serious faults: he insisted on publishing poems containing racial slurs despite the urgings of friends and editors (his rationale being that he was attempting to comment on the use of such words rather than underwrite them) and was a noted McCarthyite. Part of me wonders when and if we’ll see the work of living poets begin to populate our pop culture, or when and if white male poets from history will cease their stranglehold on our cultural imagination of what poetry is and who can write it. I think that time is very close at hand, happening now, and our pop culture artifacts will hopefully catch up.

On the other hand, Cummings’ work still moves me, just as it did when I first encountered it as a child. It’s hard to know what to do with the art of questionable men. Icelandic singer Björk chose to reinterpret Cummings work in song and was so successful that many fans don’t know the song’s lyrical source at all.

The Weird Punctuation Guy Meets the Swan Dress Girl

The ninth track on Björk’s fourth studio album Vespertine (2001) is comprised entirely of the words of E. E. Cummings’ poem “Crepuscule.”

“Crepuscule” is an antiquated (and beautiful) word for twilight, which actually fits the themes of Vespertine better than the song’s solar title: “vesper” is an archaic word for evening. “Crepuscular” describes things that are active at twilight, and “vespertine” describes things that are active in the evening, making one a kind of progression into the other.

But Björk decided to go full-on daytime and call her sonic reading of Cummings’ poem “Sun in My Mouth.” If I read that image literally, I suppose you might be able to say that a sun in one’s mouth would be shrouded, only giving off part of its light, like a sunset, but enough of the close reading—here’s the text of the Cummings poem in its entirety:

CREPUSCULE E. E. Cummings I will wade out till my thighs are steeped in burn- ing flowers I will take the sun in my mouth and leap into the ripe air Alive with closed eyes to dash against darkness in the sleeping curves of my body Shall enter fingers of smooth mastery with chasteness of sea-girls Will I complete the mystery of my flesh I will rise After a thousand years lipping flowers And set my teeth in the silver of the moon

Björk makes very few alterations to the poem’s text, and sings it word for word until about three-quarters of the way through. Then she repeats the line “Will I complete the mystery / of my flesh” twice before echoing out on the phrase “my flesh,” leaving the song with an open-ended question rather than a statement, as Cummings’ original poem does.

There is certainly something quite male about Cummings’ “I will rise / After a thousand years,” which Björk omits for a more feminine question about mystery and the body, which she underscores before ending on. In this way, she honors the original poem without rewriting any of it while also making the resulting sound-poem undeniably hers.

It’s pretty damn smart.

What’s interesting is that not many lyrics sites or fan sites say outright that the song is an adaptation of a Cummings poem. Most don’t mention it at all, others admit it was “inspired by” Cummings, and still others incorrectly note that only the first few lines are borrowed from Cummings.

We love a singular genius, and finding out that our faves have their own faves and inspirations can majorly damage our conception them if that singularity informs our respect for them. But again, collaboration, connection, and multiplicity more closely align with Björk’s body of work overall, which true fans likely know in their hearts.

The phenomenon of poems being set to music in whole cloth is in no way isolated to Björk, and musicians have long been inspired by poetry from the classical era into the modern era. But Björk’s experimental bent and Cummings’ avant-garde poetry are such a perfect marriage, it turns out, that it wouldn’t even occur to a Bjork fan that her lyrics might have their provenance in modernist poetry.

P.S.

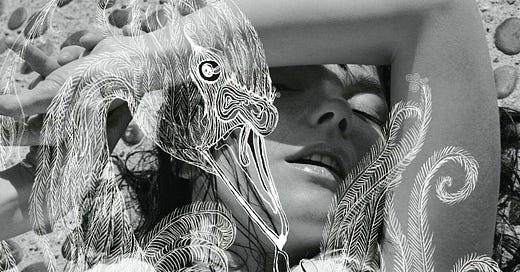

Bonus Poetry Point: Björk’s iconic swan dress from the Vespertine period takes its inspiration from the album’s artwork and totally has “Leda and the Swan” vibes. Glorious.