This is PopPoetry—a newsletter/blog-type-situation by Caitlin Cowan that you can learn more about here. If you like what you read and would be interested in having more pop up in your inbox, consider sharing this piece and subscribing.

It seems like the world is ending. Truly. I know that every generation feels this way, and I suppose that this is my moment: the twin pandemics of COVID-19 and racial injustice rage on while the sitting U.S. President continues to deny the seriousness, or even the existence, of either. We are days away from an election that has the potential to improve the situation or make it much, much worse. Unfathomably worse.

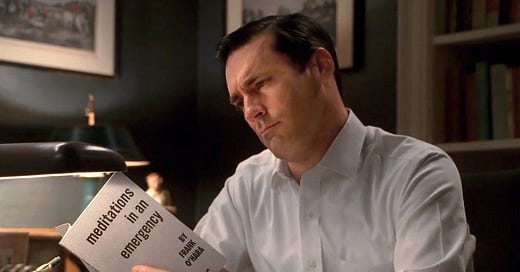

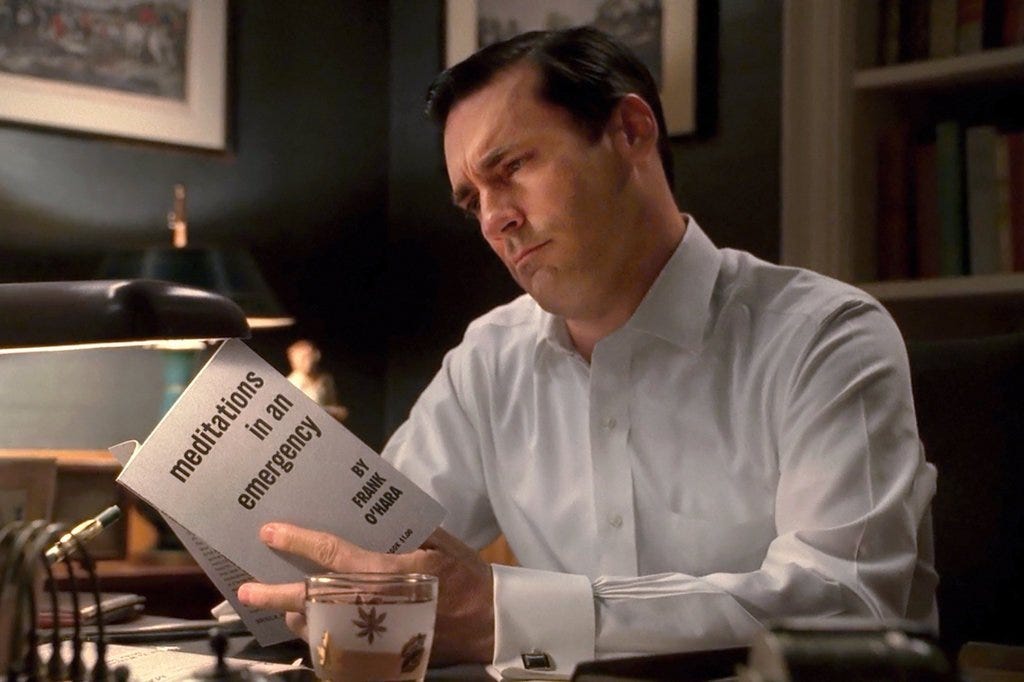

And if every generation has moments when it truly feels that the world is at an end, in the 1960s, one of those moments was the Cuban Missile Crisis. Matt Weiner’s well-heeled period drama Mad Men memorably captures the anxiety of this moment in its Season 2 finale, “Meditations in an Emergency,” which takes its name from New York poet Frank O’Hara’s 1957 collection.

As a nation in the midst of our own unprecedented emergency, we might be able to see some of ourselves in O’Hara’s book and in history, even if that history is a fictionalized account of an event that took place in 1962. Beggars can’t be choosers, after all.

If you’ve never watched Mad Men, kindly bookmark this post, binge it on a streaming service at least through season two, then come back when you’re ready. Seriously: it’s that good. But for everyone else who’s ready to think about this accomplished show, its interest in consummate New York poet Frank O’Hara, and our current emergencies, pour yourself a drink or seven and have a seat.

Unless you have a graduate degree (or two) in poetry (Hi!), you probably know O’Hara as a poet of another kind of calamity or not at all. Frank O’Hara (1926–1966) was an American poet most associated with the New York school. He is known for his approachable, “I do this, I do that” poems that chronicle the lived experience of a first-person subjectivity. His work is steeped in the sights and sounds of NYC, and his tragic accidental death at the height of his powers has cemented his place in the world of poetry even further.

O’Hara’s work bookends Season 2 of Mad Men: Don meets a stranger reading Meditations in an Emergency in a bar in the season premiere, and the season finale is named after the slim volume. The season premiere also contains a voiceover of Jon Hamm reading some of the book’s final poem, “Mayakovsky.” But the collection resurfaces in the penultimate episode as well, when we discover that Anna Draper was the one who Don mailed Meditations in an Emergency to in S02 E01.

Season 2 will see Don philandering, as he so often does. The strictures of “traditional,” highly gendered, cis-hetero-patriarchal marriage in the 1960s particularly enabled this kind of behavior (not that it’s a thing of the past), and Don isn’t even married to someone who knows who he really is (and quite literally: we’re still a season away from Betty discovering the so-called “Dick in a box”). When Betty is made aware of his most recent affair in the middle of Season 2, she withdraws from him in a kind of weak-willed separation. When Anna and Don come face to face, Don admits that he is in the middle of a private crisis. “I have been watching my life,” Don says. “I keep… trying to get into it. I can’t.”

Things are in limbo: something bad is happening, but very slowly. Something worse might still happen, but it hasn’t happened yet. To me, this feels very much like the situation in which we find ourselves in the U.S. today.

In the Season 2 finale, Betty also finds out she’s pregnant at the height of her strife with Don. Pregnancy itself is a form of waiting, a wide plain of stillness between the twin crises of orgasm and birth. And Betty’s waiting is made heavier and more poignant because she does not want the child.

These situations are the soil in which O’Hara’s book, introduced to us at the outset of the season and recalled again near its end, grows, if crookedly.

The word “meditation” and the word “emergency” are opposites, at least kind of. For those with a lot of poetry vocab, I think of their juxtaposition as a kind of “slant” connotation (e.g., close, but not quite). Meditation requires us to pause, to hold still; emergencies often demand quick action. O’Hara’s title, “Meditations in an Emergency,” requires us to think about the intersections of the personal and the societal, about thoughts versus actions, and about how all these things are the same.

This is such a critical episode in the show’s development. Pete tells Peggy that he loves her. Peggy reveals her pregnancy and Betty hers. Betty fully grapples with her damaged marriage and cheats on Don, in an act of reclamation and power, for what we are to assume is the first time. The Cuban Missile Crisis, a distillation of the anxiety of the 1960s, looms large. Don returns from the left coast that keeps pulling him back from New York throughout the series [as a quintessentially New York poet, O’Hara is a fitting choice for Don’s homecoming).

All these emergencies are personal, but they are all set against the backdrop of an enormous national danger. Does this feel familiar to you, 2020 America? Wearing a mask feels like a personal decision, but when that decision has exponential ramifications for spreading a virus throughout one’s community, that decision’s linkage to public life becomes clearer. And when personal choices bear upon the public (which is always, to my mind), they become political. The Season 2 finale, in particular, and O’Hara’s collection as a whole, asks us how we navigate the personal and the political, how we function when the world outside is just as fucked up as our inner worlds are.

For O’Hara, one answer to that vexing set of questions might be, we wait. In “Mayakovsky,” an excerpt of which Hamm masterfully reads aloud in the episode’s final moments, O’Hara writes:

Now I am quietly waiting for

the catastrophe of my personality

to seem beautiful again,

and interesting, and modern.The country is grey and

brown and white in trees,

snows and skies of laughter

always diminishing, less funny

not just darker, not just grey.It may be the coldest day of

the year, what does he think of

that? I mean, what do I? And if I do,

perhaps I am myself again.

When O’Hara writes, “what does he think of / that? I mean, what do I?” the stream-of-consciousness style belies the speaker’s real problem: he’s constantly thinking, very straightforwardly, about other people’s opinions before his own. When I read “And if I do,” I hear an emphasis on the I. If I do. In other words, if I can get a grip on myself, if I can be the one who thinks of myself rather than letting others do my thinking for me, “perhaps I am myself again.”

Suppose we can re-locate the center of our experience as our own authentic selves rather than our projections (think social media). What would happen? If we can bring that true self to bear on the world, maybe it can be a balm for the pains we experience. If Don can refocus his attention on his family, perhaps he can become whole. If he can stop viewing himself through the eyes of others—a learned tactic he uses as a suit of armor to protect the identity he stole during the war—he will grow. The poem he reads seems to resonate with him, so much so that we get the voiceover of O’Hara’s poem while Don walks the dog as a cover for his real task: mailing the sharp little book of poems to Anna like a missive.

Matt Weiner has discussed his reasoning for including the volume in the show in the first place. His comments put me in mind of Rupi Kaur, who has done a great deal to increase poetry readership in general and especially among young people but remains controversial among literary circles for her insipid hot-take haikus about love and loss. I’m reminded of a 2017 interview with The Cut where Kaur approaches a volume of Kafka at NYC’s legendary bookstore The Strand and announces, “This guy is the best.” However, she’s not talking about Kafka; she’s talking about the guy who designed the book’s cover.

That was a magical occurrence. I had studied poetry in college, and I read a lot of poetry, but I did not know Frank O’Hara. My wife took me to an exhibit between the first two seasons at the Museum of the City of New York and they had individually printed pieces of paper where you could read some Frank O’Hara poems. So I had one of these folded up in my pocket and it led me to think that Don, who was experiencing boredom after recommitting himself to his family, runs into this guy who just says he’s a suit, he’s a button-down guy.

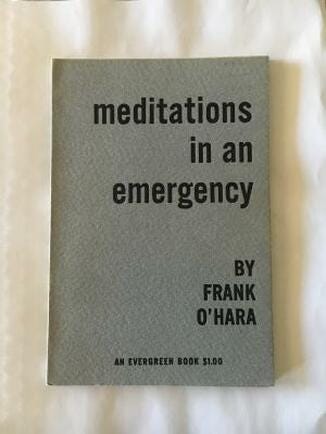

In my mind, Don bought the book ‘Lunch Poems.’ But that had not come out yet, so we had to use Meditations in an Emergency. I read a little bit of it and said, we’ll use this. It has a great cover, it’s very period, it was definitely a popular book.

We put it into the episode and then at the end, Kater Gordon, who was the writer’s assistant at the time, said, ‘Don’t you think he should read some of it? Don’t you think we should hear it?’ And I had not read the whole book. So I sat down and read that last poem, ‘Mayakovsky,’ and I said ‘What? This is the story of the season!’ It was exactly related to how Don felt in that episode. I wish I could act like it was planned that way, but it wasn’t.”

—MATTHEW WEINER

“‘MAD MEN’ and Its Love Affair With ’60s Pop Culture,” NYT, April 3, 2015

Weiner was drawn to the book’s aesthetic rather than its contents, but in a happy accident, he found that the book’s ruminative qualities mirrored his characters' struggles. Part of me is charmed by Weiner’s admission that the precise selection of the book was a “happy accident,” but that feeling is dulled by his admission that he hadn’t even read the book (!) before putting it on screen.

I read and re-read Weiner’s statement: “In my mind, Don bought the book ‘Lunch Poems.’” In my mind. Weiner imagines a 1960s guy reading a 1960s book. Lunch Poems, brimming with pop culture references and images of New York City, would have been, perhaps, a simpler choice. A more obvious choice. And it was what Weiner had originally envisioned. In the show's world, Don certainly could go on to read Lunch Poems after it was published in 1964. But as is the case in poetry, constraint (e.g., historical time, facts) produced creativity for Weiner, who ended up finding a better poetic match for the malaise of these characters.

In the end, I’m glad that Matt Weiner actually deigned to open Meditations, read one of O’Hara’s poems, and find resonance between “Mayakovsky” and the “story of the season,” as he termed it. The exposure that Mad Men potentially gave O’Hara, and poetry in general, is immense. The viewership for the episode that bears the name of O’Hara’s 1957 collection totaled around 1.75 million people, and seasons 5–7 would garner north of 3 million viewers for its premieres and finales. This mass medium beaming poetry into people’s homes, even fleetingly, makes me happy. And more importantly, it has the potential to open doors to poetry for novices and new readers.

Enormous platform aside, his anecdote of how Meditations came to be so important in the show illustrates a duality that’s inherent to all discussions of “popular” culture. On the one hand, when Weiner, like Kaur, focuses so heavily on the aesthetic of books, of the associated objets d’art that books can sometimes become, he essentially fetishizes poetry in a way that is no better than beret-sporting, finger-snapping cartoons. (To be fair, I kind of dig snapping at readings.) In other words, he makes it weird and niche.

But on the other hand, as I say so often in this space, whatever it takes to bring people to art, man. We know we aren’t supposed to, but we judge books by their covers all the time. Sometimes that leads to amazing things! I may have even bought my first volume of poetry because the painting on the front intrigued me (which reminds me… a whole post on that NYC poet and his own pop-cultural intersections is in order). Sometimes the pitch that a cover makes has far-reaching effects. It can find new audiences.

Like the poet, the advertising man is consistently tasked with speaking about and to his own time. He must situate personal concerns and questions—the strivings and desires of consumers—in their larger culture. So, too, does the show ask us to think about Betty’s pregnancy crisis against the backdrop of a push for women’s rights, about Don’s desire for a détente with his wife against the white-knuckle uncertainty of a missile scare. It’s marvelous to watch the show make these moves and use O’Hara’s wonderful book as a tentpole.

If you, too, are interested in the collection's aesthetic, it is indeed possible to find some copies (at a price, of course).

A Grove Press first edition like the one Don reads in S02E01 is available for a cool $1,890. I also wonder if the show has driven up prices for this snazzy, minimalist original printing.

If you’d like to own the collection but are looking for something in a more feasible price range, The 1996 Grove Press reissue graces my bookshelf and is available for $9 to $14.

In the title poem of the collection, O’Hara writes:

Each time my heart is broken it makes me feel more adventurous (and how the same names keep recurring on that interminable list!), but one of these days there’ll be nothing left with which to venture forth.

Very Don Draper, yes?

Without ruin, we can lose the impetus to rebuild; without crisis, we can forget the sweetness of hard-won peace. O’Hara, time and again in the collection that weaves itself through Mad Men’s second season, reminds us that each time we confront an emergency, private or public, we are blindingly, mercifully, still alive.

Subscribe if you’d like to have more writing like this delivered to your inbox! If you know anyone who might be interested in the kind of topics I’ve been writing about here, let them know or forward them a link! Thanks for reading.