The Poem That Explains Walter White

The Learn'd Astronomer: The Good Poetry of Breaking Bad, Part I

The role that Walt Whitman’s “The Learn’d Astronomer” plays in Breaking Bad is one of the first things I ever wanted to write about for PopPoetry—seeing the work of a poet being such an integral part of the show’s plot was utterly thrilling to me. And not just any show: one of the most critically acclaimed television shows of all time.

Good screenwriters choose poetry that makes sense for their characters when these mash-ups do happen, and Vince Gilligan knocked it out of the park by selecting the so-called Grandfather of American Poetry.

As always, big-time spoilers are ahead.

“The Learn’d Astronomer”

In Season 3, Episode 6, we’re treated to the first appearance of Whitman in the show’s story arc. Walter White (Bryan Cranston) and Gale Boetticher (David Costabile) are alone together in the quiet meth lab. The pair discuss their unusual paths into the meth-making business from more traditional careers.

Gale admits that he found academia stifling, that he tired of climbing the ladder. This leads him to make a reference to Walt Whitman’s poem, “The Learn’d Astronomer,” first published in his 1865 collection Drum-Taps, which was penned during the Civil War. Walt says he’s not familiar with it, and Gale admits that he “embarrassingly” (no way, man—you gotta own that!) knows the poem by heart, and so he recites it.

This is the text of Whitman’s poem, which David Costabile recites in its entirety:

When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

—WALT WHITMANIn comments sections on YouTube and in other internet corners, I’ve seen viewers marvel that men of science like Walter and Gale would be interested in Whitman’s poem because of its seeming distrust of science.

What the speaker longs for is a deeper connection with the object of scientific study: that is, the world around us.

But what’s really happening in this poem is that the speaker is weary only of the nuts and bolts of the academic discipline of science: the professors, the “proofs” and “figures,” the lecture halls and their accompanying lectures. What the speaker longs for is a deeper connection with the object of scientific study: that is, the world around us. The speaker leaves the lecture hall to marvel first-hand at the stars, an eternal symbol of the mystery and magic of our place in the universe. He seeks a transcendent experience with science, one that is deeper and richer than a lecture delivered in a dusty hall. Very Whitmanic.

For Walt and Gale, this connection with the wild, rawness of scientific principles has led them to a reckless arena: meth manufacture. Rather than teaching science or theorizing about the world, Walt and Gale are now engaged in what we colloquially call “doing science.” Using their chemistry chops to make meth, while dangerous and illegal, is exhilarating for the pair. It offers them a mainline connection to the world through their scientific skillsets, which is precisely what the speaker in Whitman’s poem is seeking.

Gale recites the poem to Walt because he believes he feels the same way. And Walt does: though he began this journey as a way to provide for his family after his impending death, by this point in the series, he’s learned that he’s in remission. Thus, he’s still in the meth game for personal and political reasons rather than financial reasons alone, and one of those reasons is most certainly the high of doing science while doing crime.

The Mystery of “W. W.”

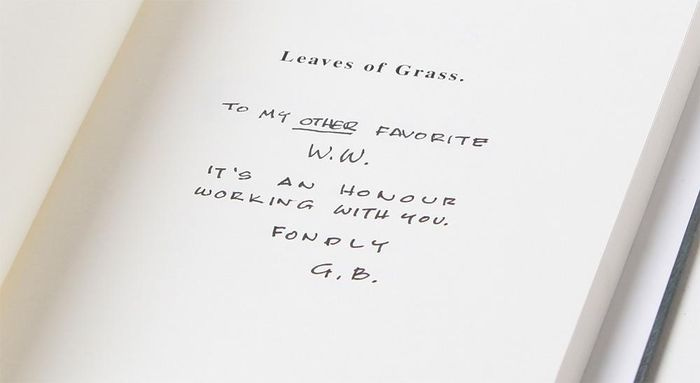

Gale is so struck by his Whitmanic connection with another “W. W.”—Walter White—that he apparently ends up inscribing a copy of Leaves of Grass, Whitman’s landmark collection that was published a decade before Drum-Taps, for Walt. We see Walt glancing at the book later in Season 3 Episode 6, but we’re not treated to a view of the inscription until later (more on that below).

If the assumption here is that Gale gifted Walt the book after their conversation, wouldn’t it have made more sense to gift Walt with Drum-Taps, the book that “The Learn’d Astronomer” was included in? Was this an oversight on set? It’s hard to say. But after their “Astronomer” moment in the lab, Leaves of Grass becomes the central Whitman work on the show.

At the end of the third season, Gale is killed. And in Season 4 Episode 4, Walt’s DEA agent brother-in-law Hank is going through Gale’s lab notes in an attempt to determine whether or not Gale is the infamous Heisenberg, the street name/persona that actually belongs to Walt.

At one point, Hank finds one of Gale’s notebooks which makes reference to a “W. W.” Hank scoffs at the note, wondering what it could mean. Speaking to Walt himself, who he does not know is actually the man he’s looking for, Hank offers a few suggestions, (one of them correct, though of course he doesn’t know this):

Right here, here at the top, it says, “To W.W. My star, my perfect silence.” W.W. I mean, who do you figure that is, y’know? Woodrow Wilson? Willy Wonka? Walter White?

Walt, by this point, is sweating, but still manages to go unidentified as Heisenberg. We don’t hear anything about Whitman until the following season after this point, but when we do, the stakes are incredibly high.

“Gliding O’er All”

In Season 5, Episode 3, we see Walt unpacking his copy of Leaves of Grass and fondly regarding it. Apparently, he has kept it and it now takes up space in his home, which will matter down the line. Later, in Season 5, Episode 8, we learn precisely where that copy of Leaves of Grass is being kept at Walt’s place: in the bathroom.

This midseason finale episode is titled “Gliding Over All,” which is an homage to Whitman’s poem “Gliding O’er All” with its language updated for modern audiences. Unlike “The Learn’d Astronomer,” this poem actually does appear in Leaves of Grass. Nice job, Vince. In this critical episode, Hank discovers Walt’s copy of the book while using the bathroom and finally puts two and two together: “W. W.” stands for Walter White. Hank’s own brother-in-law is the notorious criminal he’s been searching for.

Never did I ever think that the poet Walt Whitman would be at the center of television’s most engrossing cat-and-mouse games, which made the import of the object of the book itself even more exciting.

This poet was a shrewd choice for inclusion in this series because, like Walt White, Walt Whitman was a fearless pursuer of individualism. Though White’s pursuit of individualism is admittedly much darker and more harmful than Whitman’s—who was more inclined to loafing and leaning and elegizing dead presidents with lilacs—there’s no denying that both White and Whitman are truly American products: guided only by their gut and their sure feeling that they can chart the course of their own destinies.

These W. W.s wanted to get close to the raw edge of existence, far from the books and professors who claimed to know the world. They wanted to see it all for themselves, and though it came at a high cost for Walt, he did.

I’m giving myself a little Spring Break! PopPoetry will be on a brief hiatus: Part 2 of this series on the poetry of Breaking Bad will return, as will all of my regularly scheduled posts, on April 6. See you then!

Cool stuff. Love the analysis here. I know nada about poetry or chemistry, but it was a fun read.

I think the choice of "Gliding Over All" is an interesting one too. Gale Boetticher is such an innocent victim in this story, harmless nerd who's passionate about the craft. It hurts the viewers to see him die and it hurts his killer when he pulls the trigger.

The only solace the nitpicky viewer can find is in the titular poem. The poem speaks so positively of death, and it almost makes you think Boetticher found peace in the afterlife somehow:

"Gliding o'er all, through all,

Through Nature, Time, and Space,

As a ship on the waters advancing,

The voyage of the soul—not life alone,

Death, many deaths I'll sing."

Maybe this is Gale speaking from the grave. The exact same theme is easily reflected in that Peter Schilling karaoke song found on that tape (hilarious btw):

"Earth below us / Drifting, falling

Floating weightless / Calling, calling home".

This pop song is very similar somehow.

Wonderful analysis and explanation of the connecting threads between these real and fictional characters and story. Thank you so much.