What Poem Would You Read to a Zombie?

The Walking Dead's spinoff series, Daryl Dixon, has an answer.

Yeah, it’s another zombie media-related post! These are my interests, folks. Is my Walking Dead obsession a longstanding extension of my sense that society is collapsing? Almost certainly!

Massive spoilers ahead for The Walking Dead: Daryl Dixon, if you’re trying to avoid that sort of thing.

J’écris ton nom

As a Francophile who loves The Walking Dead, the show’s Daryl Dixon spinoff felt like it was made specifically for me. For the uninitiated: The Walking Dead is about the destruction of society following the outbreak of a virus that turns the dead into cannibalistic zombies. Daryl Dixon (Norman Reedus) is one of the show’s longest-standing members, making his first appearance in Season 1 Episode 3, “Tell It to the Frogs.” He rides a motorcycle and shoots crossbow like a mercenary, and for a long time he has a dog companion named “Dog.” He’s the epitomic badass with a heart of gold—and who doesn’t love that?

You might wonder: how the hell did Daryl make it to France from America in an apocalypse? Don’t worry—the show has a robust explanation for that.

In the series premiere, “L’âme Perdue” (“Lost Soul”), Dixon finds himself seeking refuge at a nunnery in rural France. There, he meets former party girl and petty thief-turned-nun Isabelle Carriere (Clémence Poésy, whose last name, I’d like to point out, is a homonym for the French word poésie, or “poetry”). Isabelle and the sisters are sheltering a boy named Laurent, who we learn later is Isabelle’s nephew, though he doesn’t know this. The nuns and their religious network, Union de l’Espoir (The Union of Hope) believe that Laurent is a kind of prophet or Jesus figure who will deliver them from the evil—or the dead—that walk around them. This belief is rooted in a horrifying secret from Laurent’s past.

Seriously, watch the show! I won’t say more in case you decide to check it out. Filmed on location in France, it’s worth it purely for the eye candy: Mont Saint-Michel, the Louvre, l’Abbaye De Montmajour… glorious.

In the pilot, Daryl comes upon Laurent reading something to a zombie imprisoned within the abbey. The zombie used to be Père Jean (Father Jean), who once led the abbey and served as Laurent’s teacher. What is he reading? Why, a poem, of course.

Can you imagine that? Thousands of poems fluttering down from the sky?

Pierre sang papier ou cendre

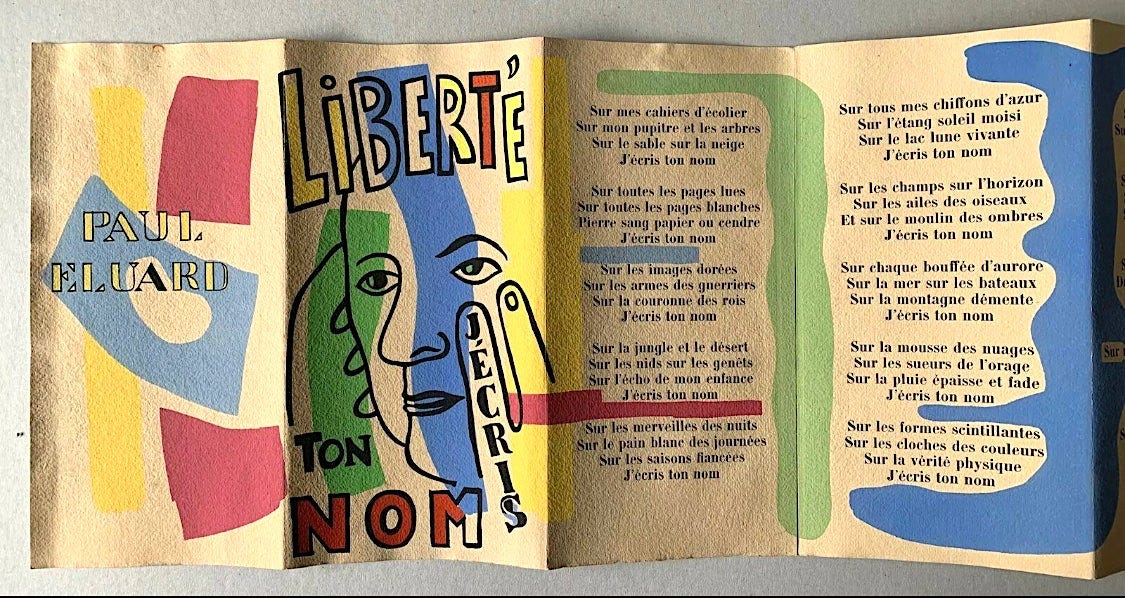

You’ll be gratified to know that Laurent reads Paul Éluard’s “Liberté” (“Freedom”) to the zombie behind bars… cute, right? Paul Éluard (1895–1952) was a surrealist poet, which is apt. Is there anything more surreal than the dead waking to walk the earth and terrorize the living?

The poem Laurent reads is perhaps Éluard’s best known, and was written in 1942 during the German occupation of France. In many ways, the world of the Walking Dead franchise is occupied as well: occupied by zombies. This gives the writers ample room to discuss Vichy France, which pops up in several episodes.

The Walking Dead has a meticulously detailed sense of time, and fan sites have compiled a citation for almost every day (!) of the story’s 12-year timespan. The collapse of society is dated to around 2010 in the timeline of the show. Laurent seems to be reading from the 1968 hardcover edition of the first volume of Éluard’s Œuvres complètes, which is shrewd. The newer edition, published in 2013, is available on Amazon, but the showrunners did a good job in selecting a book that Laurent would have actually had access to.

As a disclaimer: I’ve not published any translations, though I am a poet who speaks French and who has tried my hand at a few translations just for my own edification. I know more than most about French poetry, but I’m not a translator by trade.

I feel confident in saying that the writers made an interesting choice, here, when they changed the order of the lines that Laurent reads from the original. In the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment in the show, Laurent stands before the zombie that was once Père Jean and reads “Sur la montagne / Sur la mer sur les bateaux…” at this point Daryl stops him, worried for his safety and not just a little creeped out.

But the original version of this eighth stanza of the poem reads this way:

Sur chaque bouffée d’aurore Sur la mer sur les bateaux Sur la montagne démente J'écris ton nom

Perhaps the writers enjoyed having Laurent read the word “démente,” demented or crazy, in the scene because the scenario is so insane. Or maybe they thought they’d extend an olive branch to American audiences who speak zero to minimal French and include the simpler, more straightforward lines (bouffée d’aurore wouldn’t come up as often in French class as la mer and les bateaux). Who knows?

I prefer the shape and language of the original stanza: particularly the first line, which I’ve seen translated as “wave” or “piece.” As much as I like the phrase “on every piece of dawn” in English, as it is translated in the Dillon/Smith version, I don’t think it’s quite accurate. Here’s my translation of this stanza:

On each breath of dawn On the sea on the boats On the demented mountain I write your name

That last line of the stanza is repeated at the end of 20 of the poem’s 21 stanzas. The name being written, of course, is freedom (Liberté), finally named in the poem’s final line.

Sur mon chien gourmand et tendre

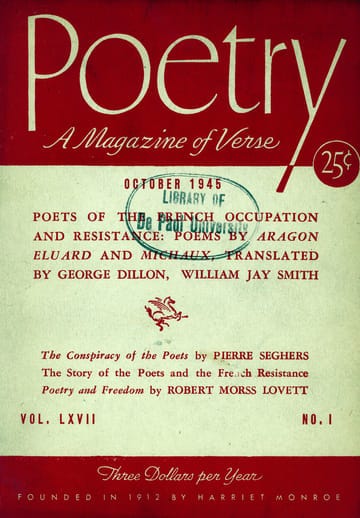

Published clandestinely in 1942 shortly after it was written, the poem was later dropped from an airplane in leaflets over occupied France as a message of hope and solidarity. Can you imagine that? Thousands of poems fluttering down from the sky? It was republished many times afterward, including in Poetry in 1945 in their special issue on the French Resistance. This translation by George Dillon and William Jay Smith is quite good, though many more amateur translations exist online.

You can hear Éluard read “Liberte” himself in the original French at the link.

Reading anyone, zombie or human, a poem entitled “Freedom” while they are literally behind bars is a good joke. But it’s also moving in that it asks us, the viewers, to reflect upon what freedom really is. Éluard’s poem is not scholarly or denotative in its description of freedom. Rather, it is mysterious, and documents the speaker’s almost intangible impulse to write the name of the second person, the “you” addressed in the poem, which is freedom, everywhere he can see. He talks about writing this word on literal objects, like desks and notebooks and also in irreal places or abstract or impossible places like “on the breath of dawn.” He feels called to freedom but seems to struggle to quite define it, but his search for what freedom really is emblematizes freedom itself.

Éluard’s description of his motives in writing the poem are similarly mysterious in that wonderful way that poets talking about their own work often have: Éluard said that he started the piece as a love poem to a nonspecific “you,” but during the writing of the poem, he realized that the feeling or the impulse he was addressing was actually the concept of freedom (So French. So surreal. So poet. ) and not a person at all.

Not a person at all, just like Père Jean. Perhaps Laurent, too, is also addressing a concept rather than a person as he recites Éluard’s poem: hope. Hope for a future where there will be freedom and ease and peace and safety and comfort in the middle of what is essentially a war, just as Éluard was in occupied France when writers were not truly free to say and write and publish what they wanted, though he did so anyway at risk to himself.

The characters on the show are waiting, in essence, for salvation. Laurent’s situation seems horrifying: when Daryl finds him reading to a caged zombie that continually reaches out beyond the bars to try to devour him, he’s worried and unsettled. But Laurent’s attitude is fundamentally no different than that of, say, Americans today.

This is the stubborn belief of human beings: that things can get better.

In a 2010 Pew Research survey, 40% of those surveyed said they not only believed Jesus Christ would return, but that he would return by 2050. In the real world and in the world of The Walking Dead, the belief that salvation is coming and that the dead will live again is widespread. If you think a kid reading a poem to a zombie is nuts, think again.

Sur les armes des guerriers

Early on in the show, a beleaguered Centers for Disease Control researcher tells the main cast members that once someone contracts what’s known as the Wildfire Virus, the human part of them is gone. Or rather, once they contract the virus, die, and then return to “life,” they will only be an animated shell of themselves: a hungry corpse. Despite this fact, numerous characters on the show struggle to deal with the zombified version of someone they love. Zombies are kept in fenced areas or rooms in houses or chained to beds or tied to walls so that their loved ones can still have them close by, no matter how terrifying and bloodthirsty they are. People find themselves unable to let go of their loved ones and somehow still see them in the disgusting, rotting corpses gnashing their teeth at them. Some characters even allow themselves to be devoured by the zombie of the person they loved.

It is this impulse that Laurent is tapping into by reading Père Jean the Éluard poem. This is the stubborn belief of human beings: that things can get better. Some of the people in this universe believe that anyone can be redeemed: even the dead. Laurent believes that the human part of Père Jean is inside the zombie that is trying to kill him, so he reads the zombie a poem to feed that human part of his being.

Poetry is perhaps the most human form of language because it serves both no purpose and extremely lofty purposes. Poetry does not help us physically survive by feeding us and providing us with water or shelter, but it sustains our souls, our conscious selves—the things we like to think set us apart from the animals and, of course, from the dead.

We’ve seen poetry used to humanize something that is not quite human before in pop culture. Vincent Price reads Johnny Depp’s Edward Scissorhands a poem as part of his “programming,” and poetry also plays a moving part in Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, by which a robot boy attempts to become human by following a poem’s riddle. It seems that we believe, deep in our cultural bones, in some forgotten hollow where the marrow lies, that poetry can make us, or keep us, human.

There’s so much discussion today about both artificial intelligence and the end of the world. We are being forced to define both what makes us human and what makes life worth living in an age when both are threatened with extinction. Poetry offers many worthy answers to these deep and important questions. Despite whatever the warped American government or the culturally bankrupt mainstream culture tells you: poetry, art, and books matter. Take a cue from Laurent: hold fast to them now and in whatever catastrophes may lie ahead.

Related

Fearful Symmetry: How Two 18th-Century Poems Speak to a 21st-Century Apocalyptic Wasteland

PopPoetry is poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post! Time for a little light apocalypse reading. Let’s go!

I Think of Kevin Prufer's National Anthem While Watching The Walking Dead

Around that time, the city grew quiet.