The Poetry of The Crown

Netflix's expensive and engrossing crown jewel offers up a heap of poetry used for various effects. Will the show's final season deliver more?

The Royals: they’re just like us, said no one ever.

Despite the Crown’s attempts in decades past to make the Windsors seem like regular folks, in recent years any guise of normalcy has withered away as royal watchers and Netflix viewers gobble up headline-grabbing stories about figures such as Princess Diana, Prince Andrew, and the Duchess of Sussex.

Perhaps it is because they aren’t like most of us that we can easily believe that poetry is a large part of royal life, an undercurrent that functions as a shared language, a tone-setter, or a rallying cry. These are just some of the ways that The Crown, Peter Morgan’s wildly successful and highly watched drama, has used poetry in its five seasons.

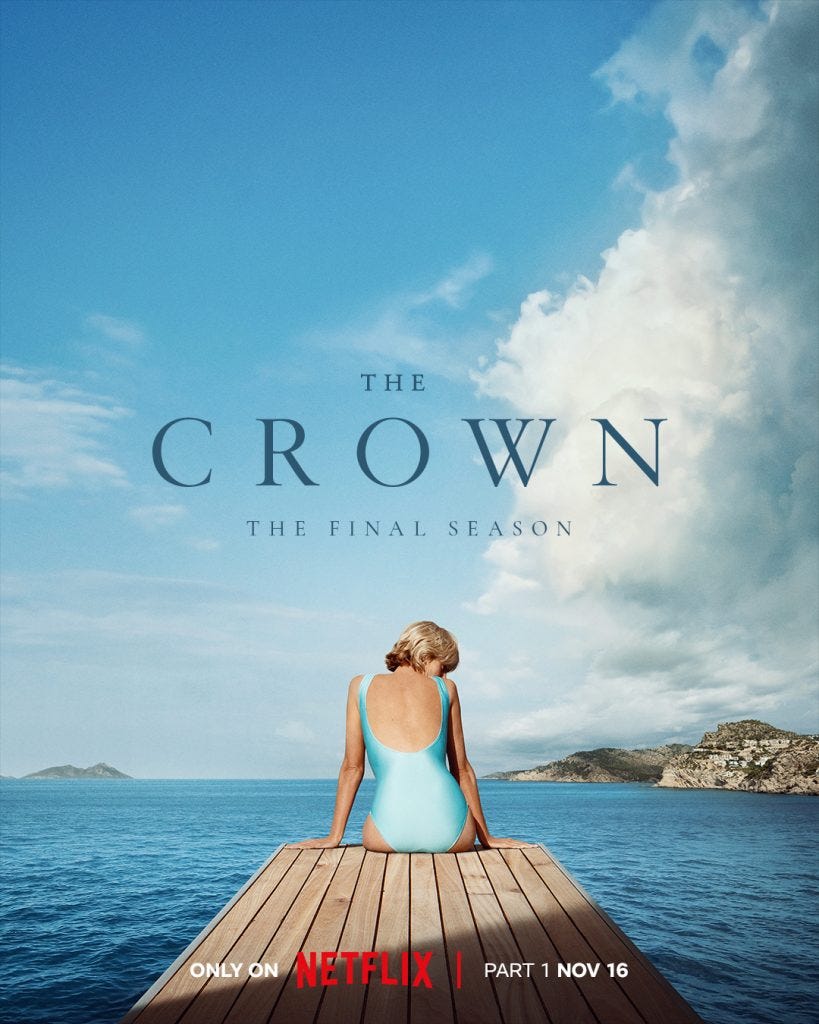

The series’ final season will air on November 16. Season 6 is the only one that will air for the first time in a world where Queen Elizabeth II, the center of the show’s universe and the longest-serving female head of state in history, is no longer with us.

“Who wants transparency when you can have magic? Who wants prose, when you can have poetry? Pull away the veil and what are you left with?” asks the abdicated Edward, Duke of Windsor, as he watches Elizabeth II’s coronation at the end of the show’s first season. Indeed! That statement might just be an apt thesis for the show itself, whose alignment with historical fact is at times spot-on and at other times fully fabricated. The Crown attempts to speak to the “big-T Truth” of the royal life in favor of sticking to the “little-t truths” about precise facts.

But the overall effect of the show is deeply poetic, scrutinizing the identity crises of highly visible people trapped in a web of ceremony and history that is nearly impossible to escape.

Not only is the show poetic: it also contains a great deal of poetry, right from its opening moments. Let’s look at the poetry of The Crown, starting from the very beginning.

Limericks

Season 1, Episode 1: “Wolferton Splash”

Just 7 minutes into the first episode, we’re treated to a pair of dirty limericks that function as centering, soothing mechanisms for George IV. The aging monarch, father of Elizabeth II, wonders if he should be concerned about his health after seeing some blood in his spit and is annoyed that his valets are having trouble buttoning his collar.

Peter Townsend, equerry to the king, steps in to work with the collar and offer the frustrated king a limerick to life his spirits.

There was a young lady named Sally, who enjoyed the occasional dally she sat on the lap of a well-endowed chap and cried “Sir! You’re right up my alley!”

It works. George counters with a limerick of his own:

There was an old Countess of Bray and you may think it odd when I say that despite her high station, rank and education she always spelled “cunt” with a K.

When poetry appears in popular culture, it often takes the form of a shared language or helps two people recognize on another, as it does here. We learn right away that the pomp and stuffiness of the royal can sometimes be tempered by a good laugh or a filthy rhyme. The veil can slip… when it does, we see glimpses of regular people ensared in the trappings of ritual and imperialism.

William Wordsworth, “Ecclesiastical Sonnet XXXVIII: Elizabeth”

Season 1, Episode 10, “Gloriana”

Just as Season 1 opens with poetry, so too does it close with it. The poetry guy on this show, if there ever was one, is photographer Cecil Beaton. Beaton would go on to create some of the most iconic photographs of the royal family in history. As photographic historian Robin Muir wrote for Vogue, “The direction royal portraiture might have taken without Beaton is almost inconceivable.”

On the show, Beaton is played by Mark Tandy, who recites poetry while he taking these photos in order to underscore the kind of effect he’s seeking and to transport the photographic subjects out of the realm o the everyday and into the realm of the eternal.

Beaton quotes the bolded lines below when photographing Elizabeth as the new queen. The poem he reads is one of Wordsworth’s ecclesiastical sonnets named for Elizabeth I, whose comparison with the emerging Elizabeth II Cecil openly engages.

HAIL, Virgin Queen! o’er many an envious bar Triumphant, snatched from many a treacherous wile! All hail, sage Lady, whom a grateful Isle Hath blest, respiring from that dismal war Stilled by thy voice! But quickly from afar Defiance breathes with more malignant aim; And alien storms with home-bred ferments claim Portentous fellowship. Her silver car, By sleepless prudence ruled, glides slowly on; Unhurt by violence, from menaced taint Emerging pure, and seemingly more bright: Ah! wherefore yields it to a foul constraint Black as the clouds its beams dispersed, while shone, By men and angels blest, the glorious light?

The gravity of Elizabeth’s new position, underscored by Beaton’s instruction about “forgetting Elizabeth Windsor” and becoming “now only Elizabeth Regina” (in other words, the Reigning Queen Elizabeth), grips her in the episode’s final moments. Heaping the gravity of the monumental reign of Elizabeth I onto the young Elizabeth II’s shoulders by engaging the “sage Lady” of Wordsworth’s poem makes the weight of her duty all the more clear.

Tennyson, “Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington”

Season 2, Episode 3, “Lisbon”

This one is tricky. And what an episode!

It’s 1957, and Philip’s difficulty in managing his role as Elizabeth’s husband has come to a head. After openly acknowledging that divorce is “not an option,” Elizabeth and Philip come to an agreement about something that would make life more “bearable” for him: namely, to increase his rank to become Prince Philip, not just Duke of Edinburgh. In Philip’s mind, this will stop the “snobbery and prejudice” that the “dreaded mustaches”—royal advisors and others who work closely with the Queen—seem to have for him due to his upbringing and background which, he argues, “nobody understands.”

Elizabeth accedes to his request, and when he is officially given the title of Prince, Cecil Beaton is on the spot again to take his official portrait. To set the mood, Beaton fawningly uses a deeply English poem that lauds a true “son of England” as he stands before the Grecian-born Philip. Here is what Beaton recites:

O, famous son of England, this is he. Great by land and great by sea. Thine island loves thee well, thou greatest sailor since our world began... Now to the roll of muffled drums, to thee the greatest soldier comes. For this is he, O give him welcome. This is he, England's greatest son. He that gained a hundred fights, nor ever lost an English gun.

Compare this text above to the actual text of Tennyson’s poem, “Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington” (stanza VI):

Mighty Seaman, this is he Was great by land as thou by sea. Thine island loves thee well, thou famous man, The greatest sailor since our world began. Now, to the roll of muffled drums, To thee the greatest soldier comes; For this is he Was great by land as thou by sea; His foes were thine; he kept us free; O give him welcome, this is he Worthy of our gorgeous rites, And worthy to be laid by thee; For this is England’s greatest son, He that gain’d a hundred fights, Nor ever lost an English gun;

They are similar, but not nearly the same. It seems that the show’s writers revised the Tennyson original to make it more intelligible to modern audiences and (don’t you think?) to avoid having to begin with a phrase that would hit the ear as “Mighty Semen…”

Clever to use a poem that discusses the death of a duke, however, because in one sense the mere Duke is passing away to make room for Prince Philip.

Limericks, Again

Season 3, Episode 2, “Margaretology”

Another classic and unforgettable episode also has poetry on offer… poetry of the raucous kind recited in the pilot.

Princess Margaret finds herself at a diplomatic dinner with none other than Lyndon B. Johnson but doesn’t let the formality of the event dampen her irreverent spirit. You have to hear these to get the full effect.

LBJ loves the limericks and offers his own, cementing his fondness for Margaret and bolstering Margaret’s belief that she is much better suited to diplomacy and people-facing functions than Elizabeth ever was or could be.

The use of bawdy limericks assures the American President that the Brits are not as stuffy as he might have assumed. The limericks function as both significations that one is intelligent and capable of memorizing things but also fun enough to discuss fornication at a state dinner.

Season 3, Episode 5, “Coup”

Rudyard Kipling, “Mandalay”

Lord Mountbatten’s recitation of poetry in the middle of Season 3 will send shivers down your spine. Mountbatten uses Rudyard Kipling’s colonialist poem to rally support for his attempted coup.

Set in colonial Burma, the poem whips the old white men in the room where Mountbatten is speaking into a kind of jingoistic fervor. Mountbatten begins to recite, then is joined by other voices who stand and blend their recitation with his as the music swells:

Ship me somewheres east of Suez, where the best is like the worst, Where there aren't no Ten Commandments an' a man can raise a thirst; For the temple-bells are callin', an' it's there that I would be By the old Moulmein Pagoda, looking lazy at the sea; On the road to Mandalay, Where the old Flotilla lay, With our sick beneath the awnings when we went to Mandalay! O the road to Mandalay, Where the flyin'-fishes play, An' the dawn comes up like thunder outer China 'crost the Bay !

The idea that poetry can do this, can hold this power, is arresting. But that the poem is imperialist and hearkens fondly to the wars and conflict while using indigenous people as props (Kipling’s protagonist dreams about the Burmese girlfriend and carefree life he had in his days in India).

Kipling has bequeathed numerous well-known works to the canon, including The Jungle Book, but his reputation has rightfully waned as discussions of imperialism and racism have changed in recent decades. Mountbatten uses Kipling’s poem to say, in essence, if you choose me to head your new government we’ll do things the way we did back in the olden days.

It’s giving MAGA. Next!

Season 4, Episode 2, “The Balmoral Test”

Charles Mackay, “No Enemies”

Margaret Thatcher, played magnificently by Gillian Anderson, recites Scottish poet and journalist Charles Mackay’s poem “No Enemies” before Elizabeth when describing her approach to politics.

Mackay was a Chartist, a member of a working class group advocating political reformin the early and mid-1900s. Anderson recites the entire poem admiringly:

You have no enemies, you say? Alas! my friend, the boast is poor; He who has mingled in the fray Of duty, that the brave endure, Must have made foes! If you have none, Small is the work that you have done. You've hit no traitor on the hip, You've dashed no cup from perjured lip, You've never turned the wrong to right, You've been a coward in the fight.

Elizabeth, who almost always has the upper hand in meetings with her Prime Ministers, seems to recognize her own inability to make enemies as a highly visible head of state. Does some part of her admire Thatcher’s grit? A life that allows her to make unpopular decisions (or, as some call them, “polarizing” decisions).

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”

Season 4, Episode 4, “Favourites”

This moving episode sees the Queen visiting each of her four children and learning that each one of them is wounded and worrisome in their own unique way. Even her presumptive “favorite” child, Andrew, and her first child and heir presumptive, Charles, irritate and disappoint her.

When touring their Highgrove residence, Charles tells his mother, “I really think I could be happy here. It’s brought something out in me. My ow little Shangri-La or Xanadu.” At this point, Charles quotes Coleridge’s poem:

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills, Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree; And here were forests ancient as the hills, Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

Charles seems to take for granted that his mother will understand the reference, though she doesn’t acknowledge it. He himself was the first heir apparent to earn a university degree, and we learn in the series that Elizabeth’s education was more limited and overseen by a private tutor. Is “Kubla Khan” so well-known that anyone of that station in England would recognize it? Or is Charles attempting to use poetry as a shared language only to learn that his mother doesn’t speak it?

It’s also interesting that Charles uses a description of an irreal place, a place Coleridge reportedly visited in an opium-induced dream, to describe his new home. It is indeed real, but like a dream, it’s almost as if he knows it won’t last.

Did I miss anything? If so, let me know in the comments! What poems from The Crown are your favorite?

If Season 6 offers up any additional poetry, you can expect to read a deep dive here in the coming weeks. Happy watching!