The Poem That Helped Jordan Catalano Get Over Himself on My So-Called Life

Among its many achievements, the short-lived cult show My So-Called Life illustrated the limits of Socratic teaching and poetry's ability to transcend time and speak to all generations about love.

It’s slightly annoying that when Jordan Catalano finally realizes that he’s in love with Angela Chase, it’s because he’s just heard a poem about a woman who is kind of commonplace and even a little gross.

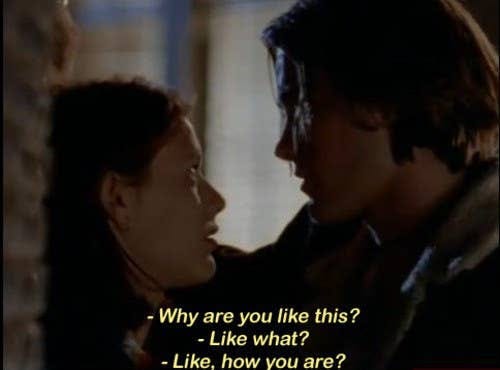

Who are these people I’m talking about? The protagonists of the cruelly short-lived 1990s television cult classic, My So-Called Life. Angela Chase, played by the luminous and already-brilliant-at-fifteen Claire Danes, and Jordan Catalano (Jared Leto) are students at fictional Liberty High School outside Pittsburgh. Their romance is a primary plot point, though the show has many threads, and includes themes of marital strife, alcohol abuse, gun violence, and more.

With just 19 episodes, My So-Called Life left a generation of viewers wanting more. But during the course of its moody and affecting first season, the characters navigate a lot of emotional ground. In Episode 12, “Self-Esteem,” we watch young people navigate the reality of the flawed self with a famous poem as their guide.

Enjoying what you’re reading? Subscribe today for weekly posts! Connecting with readers who enjoy these subjects means so much to me. Thank you!

Jordan <3 Angela

While it’s not exactly fair to say that Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130 is “about” a “gross” woman, part of me rankles when it turns out to be this particular poem that makes Jordan realize he’s in love with Angela. I would have given anything to have the looks and poise of Claire Danes when I was her age.

Danes more closely conforms to Western ideals of beauty than many of us do, so the implication that Jordan is tapping into Angela’s “flaws,” here, is a little eye-roll-inducing. However, “Self-Esteem” has a lot to say about self-esteem.

Teenagers are still trying to nurture their self-esteem and often find themselves measuring their worth in the eyes of others. They’re learning societal expectations while also developing a desire to break them. Jordan asks Angela to keep their makeout sessions in the boiler room secret, and she starts to feel bad about herself. She’s worried that Jordan is ashamed of her. The thing is, he kind of is. He’s worried that she’s not the type of girl he should be seen with. Elsewhere in the episode, Abyssinia pretends to get a bad grade on the math test in order to fit in, even though she earned a 98. Angela settles into her role as a girl who’s bad at math, even though she’s smart, too: “You just let the boys shout out the answers,” she says.

All of this gendered logic in terms of the sexual politics of adolescence is damaging and outdated, but the poem’s discussion of the role that “flaws” and uniqueness play in attraction is totally timeless.

All this sets the stage for the English class in which the students encounter Sonnet 130, which considers the eyes of others—our expectations—and ultimately casts them aside. Two students’ reactions are highlighted: Brian (Devon Gummersall) and Jordan.

Brian is also totally in love with Angela. He and Jordan both respond to the poem as a kind of representation of Angela, but for Brian this realization is easy. Angela is the girl next door, and guys like Brian, we’re told, would be lucky to get a girl like her Brian’s discussion of the poem is less moving because 1) he’s a know-it-all and 2) Angela is exactly his type, in that she’s gettable. Jordan’s realization is more moving because he doesn’t often connect to what he’s reading in English class and has trouble reading period. He also, so we’re led to believe, gets a lot of girls, girls who are older and prettier and maybe even more overtly sexy.

All of this gendered logic in terms of the sexual politics of adolescence is damaging and outdated, but the poem’s discussion of the role that “flaws” and uniqueness play in attraction is totally timeless. After he encounters the poem, Jordan braves up and takes Angela’s hand in public, signaling a moment of growing up, getting over himself, and realizing that what other people think is not necessarily a guiding light.

Sonnet 130

As is the case of so much of Shakespeare’s work, Sonnet 130 will likely give you a thrill of recognition even if you’re sure you’ve never read the poem. Our culture is so saturated with his words that reading might feel like meeting an old friend. Here it is in its entirety:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

I grant I never saw a goddess go;

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

Other than the fact that I keep referring to this poem as a sonnet, what tells you it’s a sonnet?

Sonnets are 14 lines in length and make use of various rhyme schemes. Contemporary sonnets also frequently have no rhyme scheme at all. In all sonnets, there’s typically a “turn” after the first eight lines, during which time the speaker of the poem takes a different tack, begins to have a realization, or swerves from the original line of thinking in some way, even if only subtly. Check out this post for a discussion of another one of Shakespeare’s famous sonnets and its star turn in Nomadland.

This particular sonnet turns even harder during the final couplet. The clue is the phrase “And yet,” which is followed with an emphatic “by heaven.” In other words, I’ll be damned if I don’t love her anyway, if not more.

If you translate the somewhat stuffy “belied” in the final line as “disguised,” you learn that the speaker believes that flowery language disguises or hides the real selves of those who are described as having white breasts and rosy cheeks. My girl is just as perfect as yours.

The form of the sonnet is excellent for inquiry, and by that I mean it’s just enough room in which to pose a question and, after some consideration, go a little distance toward discovering the answer. One way to understand Sonnet 130’s inquiry would be like this:

Situation: My love does not conform to common descriptions of beauty.

Question: If my love is unlike the descriptions I’ve come to know, how can I adore her as I do?

Answer: Her “flaws” make my love unique. I love her because of them, not in spite of them.

The speaker described the comparisons between, for example, roses and rosy cheeks, as “false.” Descriptions (and, in our time, depictions) of beauty are mostly exaggerated and unrealistic. The speaker begins by comparing his love to those descriptions and finds her wanting. But he realizes that this makes her rare and special. Having breath that “reeks” and wiry hair and “dun” or grayish-brown breasts does not sound beautiful, but the person the speaker describes is beloved anyhow. And this is exactly what real love looks like: radical acceptance.

Teaching Poetry

Partway into the show’s first and only season, we learn that Jordan has low literacy skills. To that point, the other students in the school had perceived Jordan’s academic shortcomings either as a signifier of his coolness or his stupidity. As it turns out, neither is true, though the show didn’t have as much time as we might have liked to explore the aftermath of this revelation, as a second season never came.

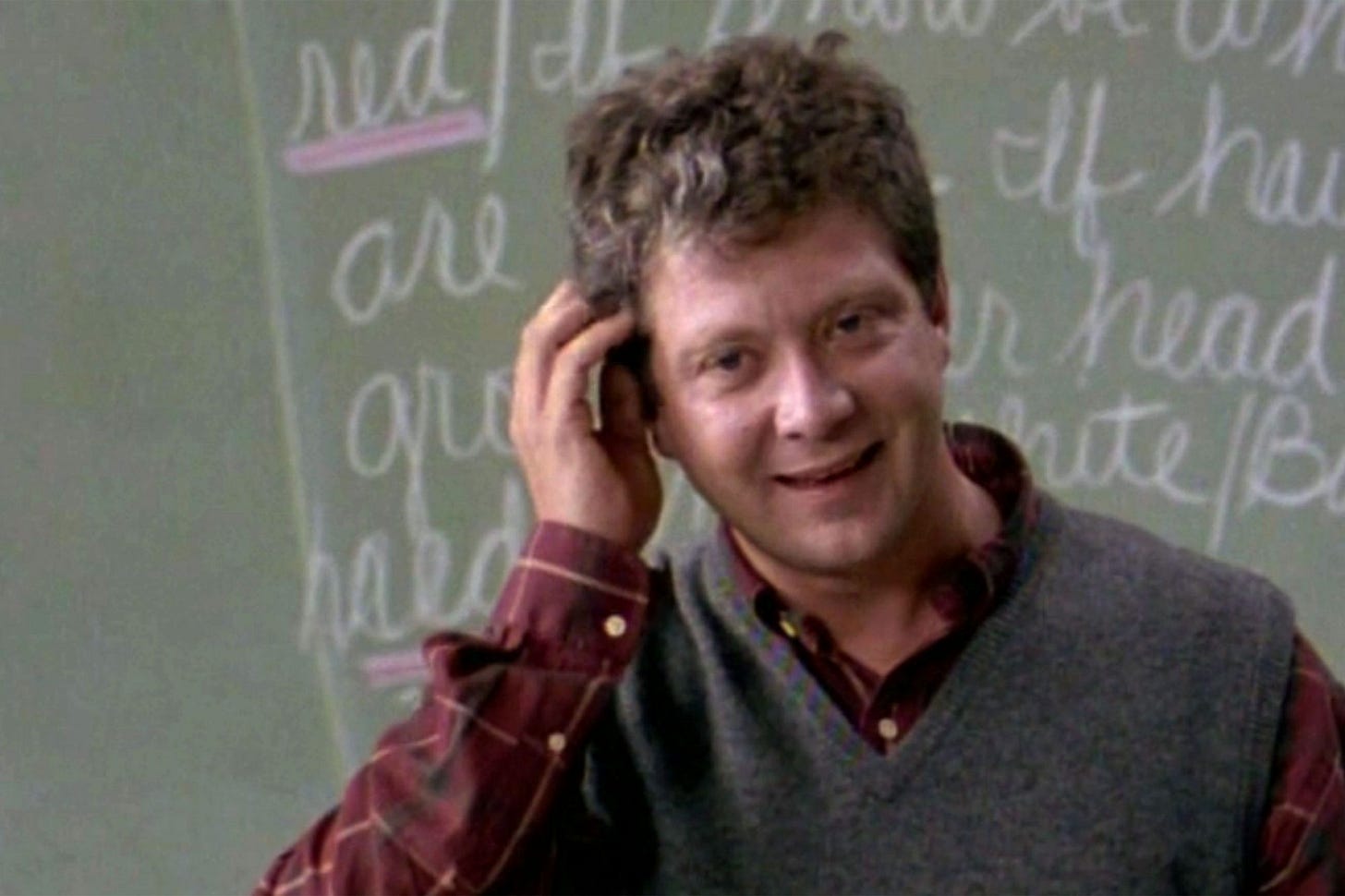

In the Episode 12 scene where the class confronts Sonnet 130, Leto does a fantastic job of telegraphing Catalano’s slow realization of what the poem means as well as his inability to fully explain it.

Our auditory comprehension is traditionally lower than our visual comprehension when it comes to reading, so it seems unlikely that the teacher’s reading of the poem aloud would help Jordan as much as it seems to, but it’s possible. All learners are different, and we really have no idea what works in education, as this thread memorably pointed out.

The above scene also highlights how “traditional” Socratic teaching methods that ask students to create a dialogue with their teacher do not work for all students. This is one of many reasons why students hate poetry: they’re expected to just “get it” after a cursory reading, and if they don’t, they assume the entire genre is not for them. Nothing could be further from the truth—poems are like paintings: they get better the longer you look at them. The first hearing of a poem is like a fireworks display: Beautiful, but vanishing. Even the most ardent readers need to linger and loll in the words in order to fully grasp them. It’s up to educators and writers and people like yours truly to continue to work to change the way that young people are introduced to and engage with poetry.

Against all odds, Jordan has a revelation when his teacher reads out the poem and demands insightful critique instantaneously. In this scene, Jordan is about to answer his teacher’s question—a very rare occurrence for him—and not because he thinks he has to. He’s about to speak because he wants to. But as so often happens, the smarty pants kid who’s comfortable raising his hand, asking questions, and speaking in public (someone with privilege) pipes up first.

Mr. Katimski: So he’s… not in love with her?

Jordan: Yeah… he is.

Mr. Katimski: And why is that? Why is he in love with her? What is it? What is it? What is it about her?

Jordan: … … …

Brian: That she’s not just a fantasy. She’s got, like… flaws.

Brian Krakow, y’all. Jordan doesn’t stand a chance.

Mr. Katimski (Jeff Perry) is leading the students to worthwhile observations, but the manner in which he’s doing it is alienating to all but the most vocal learners. Simply reading the poem aloud before asking students what the poem is about and expecting brilliant answers is insufficient for students with different learning abilities and inappropriate for students who have learning disabilities, like Jordan. High school learners, in particular, benefit from techniques that make the poem more real to them.

Those who came of age in a classroom that was managed like Mr. Katimski’s might be wondering what the alternative looks like. Author and educator Louisa Newlin uses many different techniques to help students learn about the English Sonnet, including freewriting, studying and listening to contemporary songs about love, and asking students to act out the sonnets as plays. Her lesson plan on the English Sonnet and many others are available online through the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Jordan and Brian hold Angela in their mind in order to understand the poem, but it should be possible for students to read and feel moved by poems even when the situations they describe are very unfamiliar to them. Using different techniques to spark their imaginations, seed empathy, and get their metaphorical hands dirty is the pathway to this kind of learning—not empty, self-serving call and response.

Whenever I rewatch My So-Called Life (which is… a lot) I’m struck by the novelty and difficulty of casting a 15-year-old to play a 15-year-old. That innocence coupled with a hunger for the new and the grown-up is so raw in Danes’ performance. I would have liked to see her react to the poem and its message, as well. Ultimately, the demands of the show kept the young Danes from coming back and contributed to the show’s demise. Being a teenager ended up taking precedence over playing one on TV, even after she won a Golden Globe (!) for her role on My So-Called Life.

This seems sort of perfect in light of the show’s generous and empathetic overarching theme: growing up is hard. We can “yeah yeah yeah” all we want, but I mean it. That the show was ever made is a delightful triumph. And attempting something we’re not sure we can do… that’s Duende, that’s teenagerhood, and that’s what the show was, too. I think that’s really beautiful.

As Angela might say, “So beautiful… it hurts.”

Pop Palate Cleanser

We’ve got plenty of Shakespeare’s sonnets and sonnets by white male authors out there in the pop-culture ether. Take a moment to look at the way Marilyn Nelson uses the sonnet form in A Wreath for Emmett Till. This book-length crown—a highly complex and finely wrought series of interlocked sonnets—uses the form’s capacity for inquiry to ask important questions about Till’s death and the fight for racial justice. Nelson reads the two sonnets I’ve included below in the following video.

IV

Emmett Till’s name still catches in my throat,

like syllables waylaid in a stutterer’s mouth.

A fourteen-year-old stutterer, in the South

to visit relatives and to be taught

the family’s ways. His mother had finally bought

that White Sox cap; she’d made him swear an oath

to be careful around white folks. She’s told him the truth

of many a Mississippi anecdote:

Some white folks have blind souls. In his suitcase

she’d packed dungarees, T-shirts, underwear,

and comic books. She’d given him a note

for the conductor, waved to his chubby face,

wondered if he’d remember to brush his hair.

Her only child. A body left to bloat.V

Your only child, a body thrown to bloat,

mother of sorrows, of justice denied.

Surely you must have thought of suicide,

seeing his gray flesh, chains around his throat.

Surely you didn’t know you would devote

the rest of your changed life to dignified

public remembrance of how Emmett died,

innocence slaughtered by the hands of hate.

If sudden loving light proclaimed you blest

would you bow your head in humility,

your healed heart overflow with gratitude?

Would you say yes, like the mother of Christ?

Or would you say no to your destiny,

mother of a boy martyr, if you could?

If you’re interested in learning more or teaching the sonnets of Black writers, bookmark this excellent and rigorous lesson plan and overview of “Unfettered Genius: The African American Sonnet” from the Yale National Initiative.

P.S.

Could this translation of Star Wars in the style of epic poetry make readers feel more comfortable with classics like Beowulf and The Odyssey? Here’s hoping!

Talk about bringing poetry to the people: a public art installation located in Dubuque, Iowa features a phone booth loaded with 800 poems available to anyone who lifts the receiver. The TelePoem booth will be open for the next year.

Armando Ianucci, writer and director of Veep and The Thick of It, has written a mock-heroic book-length poem about Covid, Brexit, and more. Wild.

I know; it’s a poem! Not something I expected to do, but glad I did. Extract in today’s @guardian and @guardianBooks . Whole thing out in November x https://t.co/DD6xnOc8rwArmando Iannucci's epic Covid poem: 'It's my emotional response to ... (the Guardian) here do you start with the pandemic? Add your highlights: https://t.co/f24vBW09nH #writing

I know; it’s a poem! Not something I expected to do, but glad I did. Extract in today’s @guardian and @guardianBooks . Whole thing out in November x https://t.co/DD6xnOc8rwArmando Iannucci's epic Covid poem: 'It's my emotional response to ... (the Guardian) here do you start with the pandemic? Add your highlights: https://t.co/f24vBW09nH #writing Writing Briefly @WritingLife_b

Writing Briefly @WritingLife_b

Did you enjoy this post? Subscribe! You’ll get thought-provoking explainers, writing prompts, and discussions about poetry, creativity, and the writing life delivered to your inbox along with a heaping helping of pop culture. As Angela Chase might say: so just, like… think about it?