Call the Midwife Uses a Lorca Poem to Illustrate Queer Love

my heart, / and my hat, they hurt me

PopPoetry is a poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. Check out the archive to see other TV shows, movies, songs, and films whose intersections with poetry I’ve covered. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post!

PBS’s highly acclaimed Call the Midwife is a great way to burn through your mascara. I’ve spent many a weekend sobbing in front of the television watching this show, thanks to the music, the imperiled babies, and Vanessa Redgrave’s soothing narration. I was really excited to see some poetry pop up in episode 2 of Season 6: Lorca’s impeccable “Es Verdad” (“It’s True") is recited in its entirety by Nurse Crane in an attempt to soothe Delia’s heartache.

Looking at this episode of CtM is an excellent way to introduce the focus of this newsletter, blog, or whatever you want to call it: poetry and popular culture. Though there’s certainly nothing “lowbrow” about this particular show (I leave the closed captions on to catch every inscrutable turn of phrase, from British slang to the spelling of “Mother Jesu Emmanuel,” “Akela,” and “Babycham”), the intersection of poetry with television, even verbose British period pieces, is fascinating because of one’s mass appeal and the other’s relatively more niche status.

Let’s get to the Lorca. Here’s a translation of the poem that’s recited in the show:

IT’S TRUE

Ay, the pain it costs me

to love you as I love you!

For love of you, the air, it hurts,

and my heart,

and my hat, they hurt me.

Who would buy it from me,

this ribbon I am holding,

and this sadness of cotton,

white, for making handkerchiefs with?

Ay, the pain it costs me

to love you as I love you!

—Federico García Lorca

Call the Midwife has always been a show about two things: women and love. That love sometimes takes the form of the bond between mothers and babies, between husbands and wives, or, interestingly, between nuns and their god. But in 1962, the romance between Patience “Patsy” Mount and Delia Busby, between any two women, is still taboo (not to mention illegal). When Patsy (Emerald Fennell) decides that she must return home to see her dying father in Hong Kong, Delia (Kate Lamb) is simultaneously crushed and supportive. Their love is secretive; up to this point, they have been able to keep the myriad residents of Nonnatus House in the dark. But early in the episode, Nurse Crane (Linda Bassett) happens upon Delia exiting Patsy’s room one night (both are clad in their pajamas) and merely stops at a distance to watch them without judgment. This covert observation proves useful at the episode’s end, as it allows Nurse Crane to comfort Delia in the wake of Patsy’s departure.

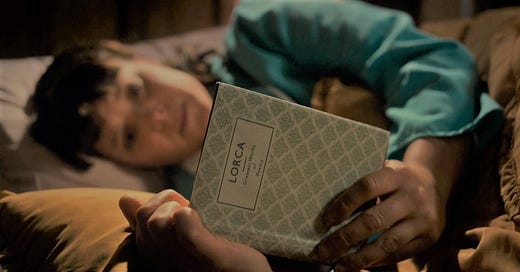

After Patsy has said her goodbyes, Nurse Crane, clutching a Spanish-English dictionary, runs into Delia in the corridor. The older nurse notes that she studies Spanish as a hobby. Delia, attempting her usual pleasantries despite the sadness she’s drowning in, says she might pick it up herself. When she sees Delia’s glimmering eyes, wet from crying, Nurse Crane asks the young nurse if she may recite a poem. Reciting “Es Verdad” in translation, Linda Bassett’s performance is convincing and comforting: she looks around as she recites it, as if she’s reading the words in the air. At the conclusion, she notes that the words are not hers, but those of Lorca. Delia is visibly touched by the recitation, as well as Nurse Crane’s advice that love is always worth the pain it causes us. The closing shot of the episode sees Delia crawling into Patsy’s bed with Nurse Crane’s period-accurate copy of Lorca’s collected poems for the night.

Lorca had been dead for some twenty-five years in the world of the show, but his work, then as now, holds a scintillating, timeless power. “Who would buy it from me, / this ribbon I am holding,” the poem asks, “and this sadness of cotton, / white, for making handkerchiefs with?” In this way, the sadness of cotton, beautifully, becomes a remedy unto itself. The cotton, woven into a handkerchief dries the tears that it has created, suggesting that the sadness love causes is part of the love itself, and therefore to be cherished, used, and carried with us, just as a handkerchief is.

Call the Midwife is always quick to remind us of life’s dualities; many of the closing monologues urge us to take the bad with the good, to recognize that life is made up of both sorrow and joy. Asking us to cultivate a deeper appreciation for the hard times and the lessons they teach us is one of the show’s many gifts, and Lorca’s poem is right at home, here.

Though his death was politically motivated, many cite Lorca’s own homosexuality as an additional factor in his tragic assassination, making Nurse Crane’s recommendation all the more poignant. Whether we are to take this historical fact in stride as part of Nurse Crane’s shrewdness or as a direct exhortation from episode writer Harriet Warner is up for debate. But one thing is clear: as viewers, we are to grieve the millennia of hardship behind and the decades of hardship to come for Delia and other queer people like her. (Up for a brief history lesson? The deeply restrictive Sexual Offences Act of 1967 was still five years away for women like Delia in 1962, and homosexuality wasn’t fully decriminalized in the UK until 1982). Though she is tucked into bed with her lover’s perfume and Lorca’s book for now, heartbreak and separation are, chillingly, some of the best consequences of the still-forbidden love she has for Patsy.

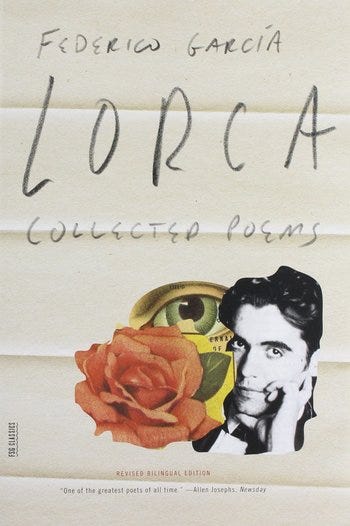

And so, we’re left only with Lorca’s radiant words. For me, books have a talismanic power, and my first impulse was to see if I could own a copy like the one in this episode. So far I haven’t had any luck, but I have come across a stunning array of vintage Lorca books. Though it’s not the same as Delia’s volume, the readily available bilingual edition of Lorca’s Collected Poems from FSG is no slouch, either.

Before reciting “Es Verdad” in translation, Nurse Crane admits that she studies Spanish because it “keeps [her] occupied, prevents the mind becoming rusty.” This admission, for me, erases the deeply British confession that she later makes: namely, that she would rather read Tennyson than Lorca any day, even though the latter’s words “move [her].” She has, it seems, betrayed herself: just as Lorca’s and Delia’s loves are culturally forbidden, so too is Nurse Crane’s love of Lorca’s poetry. This episode, and this interaction, calls us to question the messages that our culture sends us and instead listen to the emotion that springs at our soul’s root, to the deep song Lorca spent his life naming and theorizing. Reading Lorca, and, indeed, knowing the lives of others who are not like us, keeps our minds, and our souls, from rusting shut.

This post originally appeared on the author’s personal website.