Lessons in Creativity I Learned from Regina Spektor

The Nobel Prize-winning poet tucked into Regina Spektor's "Après Moi" teaches us a lot about how she understands creativity and how we can harness its power for ourselves.

You’re reading PopPoetry, a newsletter about pop culture, creativity, and poetry written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. Check out the archive to see other TV shows, movies, and films whose intersections with poetry I’ve covered. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post!

Singer-songwriter Regina Spektor’s story is American in its structure: a young ingenue arrives in New York City, starts from nothing, and soars to unimaginable heights. But her soul is Russian, which imbues her music with an untouchable surety, frankness, and otherworldliness.

You might know Spektor as the singer behind the theme song to Orange Is the New Black, her breakthrough single “Fidelity,” or the glottal, weird, wonderful Soviet Kitsch, her first major-label album released after making three self-released albums in the early 2000s.

In what sounds like a plot point from a doorstopper-sized Russian novel, the classically trained Spektor had to leave her piano behind when her family left Moscow when she was 9. This was during the Perestroika period that ended with her family emigrating to America and settling in the Bronx. She resorted to practicing on hard surfaces, as a former teacher had taught her, until she was able to practice on a real instrument again.

She cheerfully (I swear to you, cheerfully) mimics this action of practicing on a table for an interviewer with Noisey in 2016:

Though she is fully bilingual and the aesthetics and concerns of Russian culture inform her work, there isn’t a lot of Russian language in her music. Even on Soviet Kitsch, the album where Spektor appears on the cover in her grandfather’s Soviet-era military garb, no Russian language appears. Ne russkiy. But in her song “Après Moi,” off her 2006 album Begin to Hope, Spektor launches into a rare, rich, and deeply felt moment of Russian.

What’s she singing? Lines of Russian poetry.

Whether you understand Russian or not, there’s much to be learned as a creative person from Spektor’s inclusion of Pasternak and her work overall.

Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.

—T. S. Eliot

As a huge fan of Regina Spektor and as a poet myself, I’m definitely within my wheelhouse, here. But as a translator or scholar of Russian, I’m out of my depth.

I’m reminded of my shock on the first day of my Russian Literature course at the University of Michigan, which was promised to be for both speakers and non-speakers of Russian. My professor launched into speedy, fluid Russian from the first moment of the class, and only stopped when she finally landed on my widened eyes. “Oh, I forgot that this was for non-majors, too,” she said, a tad annoyed. I was the only non-Russian speaker in the class, a real fly in the ointment.

How I wished that I did speak Russian. (Who knows? Maybe there’s still time for me!) I speak French and have dabbled in French translations, but I have no background in the Russian language, though I am an enormous fan of Russian poetry.

Yevtushenko, Mayakovsky, Tsvetaeva, Akhmatova… truly an embarrassment of riches. (See the Pop Palate Cleanser below for more on Tsvetaeva.)

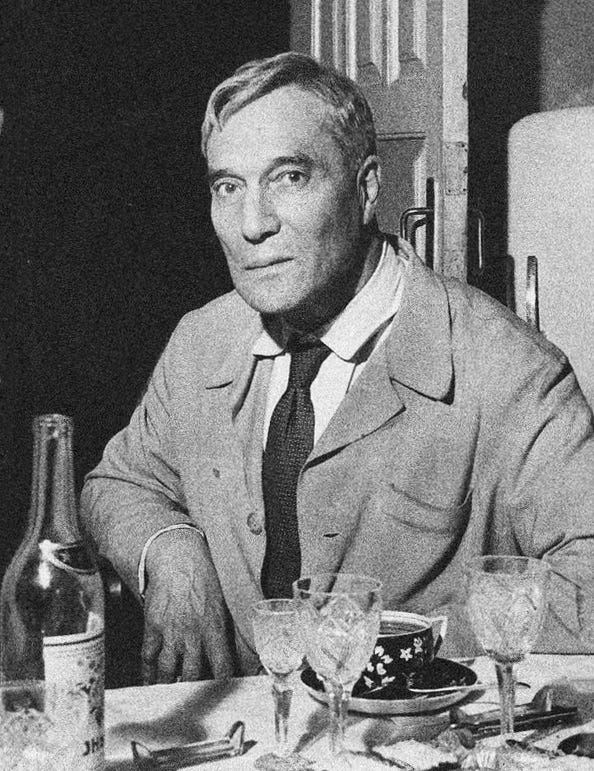

I’m less familiar with Boris Pasternak, who was a contemporary of Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva, and Mayakovsky, though he is arguably just as well-known if not better-known. Pasternak was the author of Doctor Zhivago, the 1957 novel that was rejected for publication in the USSR and later went on to win a Nobel Prize that the leaders of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union forbade Pasternak from accepting. The novel was made into a much-lauded film starring Omar Sharif and Julie Christie in 1965.

But decades before he became “that guy who wrote Dr. Zhivago,” Pasternak wrote and published poetry, as he continued to do throughout his lifetime. His 1922 volume My Sister, Life, has become a jewel in the canon of Russian literature as well.

It’s Pasternak’s “February” that Spektor quote-sings in the middle of “Après Moi,” a choice Spektor made to enact a direct linkage to Russian her heritage in a way that was expansive. In a 2006 interview with Jon Caramanica for New York Magazine, Spektor talked about the power of referencing those who have come before us:

She’s still reaching backward, though. For the first time, in “Après Moi,” Spektor sings in Russian, quoting from the late poet and Nobel laureate Boris Pasternak. “I read a lot in Russian. I’m very connected to the language and the culture,” says Spektor, who is fully bilingual. (She also reads Hebrew.) “But I can relate more to a Russian person my parents’ age than one my own age. I’m more of a regurgitator, an homage payer.”

I’m utterly entranced by Spektor’s performance of this song at Austin City Limits in 2007. Her charming, playful demeanor when she hops on stage quickly melts into studied, fiery passion. Watch the audience’s reaction to her beginning to sing in Russian around 3:05.

Spektor could have payed homage to Russia, however, by merely singing her own lyrics in Russian, or by singing a television jingle or a list of random words in Russian. But the first time Spektor sings in Russian on a record she sings poetry.

What does this tell us? It tells us that poetry is powerful, drenched in meaning and history, and always, always, always at our fingertips and ready to speak if we’re willing to hear it.

Poetry is language dialed to 11.

Lesson 1: It’s OK to enjoy something before you understand it.

Singing in Russian on a record that’s mostly in English means that a certain portion of your audience won’t understand you. But the sound and emotional urgency with which Spektor sings, along with the song’s surrounding context in English, gives us a taste of the poem’s vibe before we even attempt to translate it.

And what if you never bother to look it up online or crack a book? To me—that’s OK. It might be a controversial idea, but it’s fine to enjoy portions of art that elude your understanding for whatever reason you can find.

As an artist or creative, you have to be at peace with the idea that some (or even all) of your audience will not engage with your work as deeply as you wish they would. They’re not going to get every nod and reference, and they won’t be as dazzled by your details as you might hope.

There has to be enough room in your work for all kinds of appreciators: the ones who love digging into the bedrock of a mid-century Russian poet (raises hand) and others, like the audience members who whoop and cheer when they merely hear the sounds of another language in the ACL video above, who are content to understand the Russian language they hear as a mere marker of Spektor’s heritage that adds to their experience of the song’s literal revolutionary themes.

By that same token, enjoyment can lead us like a trail of breadcrumbs toward understanding. We can use a word that comes to us in a poem before we know what it means, then dig into why we chose it and why we enjoy it in a kind of back-and-forth dialogue. We can also scrutinize the things we enjoy aesthetically in order to develop our intellectual “understanding,” too.

That’s kind of what I’m up to here on PopPoetry, and maybe you are, too.

Poetry is like a bird… it ignores all frontiers.

—Yevgeny Yevtushenko

So this Pasternak poem… what is it?

The verse that Spektor sings is the first four lines from Pasternak’s “February”:

Февраль. Достать чернил и плакать!

Писать о феврале навзрыд

Пока грохочущая слякоть

Весною черною горит

This quatrain is sung twice. Transliterated, this verse is:

Fevrale dostat chernil I plakat

Pisat O Fevrale navsnryd

Poka grohochushaya slyakot

Vesnoyu charnoyu gorit

As for the English translation, I defer to the work of Russian readers and speakers who have translated Pasternak’s work. I love reading about theories of translation and comparing what is lost and gained through different translations, and you can see some of that happening in this blog post and its comments.

I’m fond of this translation by Lydia Pasternak Slater, Boris’s sister. In her translation, this is how the verse appears:

Black spring! Pick up your pen, and weeping,

Of February, in sobs and ink,

Write poems, while the slush in thunder

Is burning in the black of spring.

The second time Spektor sings these lines, she does so with different intonations, emphases, and notes. She has said that she enjoys manipulating the pronunciations of words in her songs, a practice which has a relationship to her learning English by hearing it on television, investing in the sounds of the words before their meanings became attached to them. See Lesson 1.

Ain’t language fun?

What strikes me about Spektor’s performance of these lines from Pasternak is that they come at the emotional height of the song. It’s as if when Spektor runs out of not only English words but also her own words, she reaches for poetry. And it feels almost as if she reaches for its music just as much as its meaning. That impulse is so deeply human, and it’s precisely how I interact with poetry myself.

Lesson 2: Use the work of artists you know and love as a scaffolding, but don’t be afraid to pull it away later.

The Pasternak lines form a little nucleus in this song, but the surrounding material is all Spektor.

Looking to artists that inspire us and building our work literally upon theirs is a valid technique, particularly in early drafts or experiments. In “Apres Moi,” Spektor uses just enough of the work to make a connection without losing herself in the work of someone else.

When you’re creating something with the “help” of someone else’s creative work, it’s important to attribute it. But it can also be a good exercise to pull away the scaffolding of the inspirational work to see if what you have made can survive without it, either temporarily or permanently. Spektor’s song certainly can, but its presence there feels critical.

For example, you might try writing an essay or story or poem with the first line or sentence borrowed from someone else, then erase it when you’ve finished. What happens?

Poetry is the lifeblood of rebellion, revolution, and the raising of consciousness. —Alice Walker

In terms of linking the meaning of Pasternak’s poem with her own song, the question of what a given poem means in translation is infinitely, and I truly mean infinitely, more fraught. In the NPR interview linked above, we discover that Spektor understands the poem this way, though she admits that she can’t capture all the “colors” of it in English:

MS. SPEKTOR: Well it’ such a particular poem. It's like translating, I don’t know, Shakespeare. Like you need just—at least I can’t capture all the colors. But it starts out, February to take out the ink into me. One must always write about February while weeping. It feels very good to sing in Russian, you just feel so good inside my body.

There’s something very narrative about many of Spektor’s songs, and when songs are narrative, they begin to veer into the territory of poetry, at least for me. Spektor’s verses about oppression, the power of the many against the few, and the endurance of the human spirit coalesce into Pasternak’s historical view of the same themes, restated with a new power that evokes the landscape of Russia.

Pasternak’s rebellious poem about making art against an onslaught of suffering is, unfortunately, relevant in our time as well as his.

Lesson 3: The materials you have are the right materials; use what you have and what you know.

We are at our most powerful when we are speaking directly from the source of our experience. You can fight me if you want to, but that’s what I believe. It’s how I write and how I teach, too.

Sometimes my students stamp their feet and fume because they want to reserve the right to write from the perspective of any race, gender, nationality, or identity in the name of art. These students are usually white and mostly male.

Cultural and experiential appropriation leaves one at best in a position of diminished integrity and at worst harms communities of people whose lived experiences are rooted in the viewpoints that we are imagining in our heads.

What’s more, the most powerful art that I have ever consumed is always created by those who are using the emotional and intellectual material of their lives to speak to others. What story can be told by only you? What viewpoint is most unique to you? Start there instead.

Spektor does this in terms of the content of her songs, but I also think she’s a lesson in using what you have in terms of her dogged attention to her musical artistry. We can extrapolate this as far as we want to: No computer? Write by hand. No paint? Use dirt. Many a creative person has thought to themselves “if only I had a studio” or “if only I had the right supplies” or, most often, “if only I had the time.”

Issues of privilege and access are in play when we talk about having time for creative work, but in most cases, if we don’t have time, we have to make the time in order to live a creative life.

The next time you find yourself making an excuse that takes you away from your creative work, repeat after me:

No piano? Use the table.

Pop Palate Cleanser

Marina Tsvetaeva is one of the most celebrated poets in Russian literature. Her life was brilliant and too brief, punctuated by several once-in-a-lifetime tragedies that were all too common to those in her era. Tsvetaeva’s mother was a concert pianist, but passed away when Tsvetaeva was just 14. She traded in musical studies for poetry, and published her first book at 18. Pasternak once referred to her as “the most Russian poet of us all.”

Her depictions of women’s life during a turbulent period in Russia’s history are jarring yet shimmering with an eye so keen it might as well be a painter’s. She corresponded with Rilke and other luminaries of her time, and her work was widely admired.

She spent time in exile during the Russian Revolution, lived in relentless poverty, found herself cut off from access to work and opportunities, and suffered the loss of several of those closest to her: her husband was executed and a daughter died of hunger in a state orphanage where Tsvetaeva had been forced to place her. It’s been suggested that the predecessor apparatus to the KGB had also pressured her to become an informant. She took her own life at the age of 48 in 1941.

Ilya Kaminsky and Jean Valentine translated many of Tsvetaeva’s poems, several of which were later published in Poetry in 2012. This excerpt from “The Desk” is full of a kind of grit and transcendence that, if you like Spektor, might resonate with you:

Fair enough: you people have eaten me,

I—wrote you down.

They’ll lay you out on a dinner table,

me—on this desk.I’ve been happy with little.

There are dishes I’ve never tried.

But you, you people eat slowly, and often;

You eat and eat.Everything was decided for us

back in the ocean:

Our places of action,

our places of gratitude.You—with belches, I—with books,

with truffles, you. With pencil, I,

you and your olives, me and my rhyme,

with pickles, you. I, with poems.

Read more of this poem here.

P.S.

Archer took two cracking swings at slam poetry in its brand-spanking-new Season 12 episode, “Lowjacked.” A character who mentioned they wanted to pursue their “dream” of being a slam poet was thoroughly roasted. Different than the “slam poetry doesn’t make sense” trope, and even shittier because it suggests that slam poetry isn’t worth pursuing at all (false, big time).

In Ted Lasso’s Season 2 episode “The Signal,” Hannah Waddingham’s character Rebecca swoons over a potential online dating match who texts her a line from Rilke: “Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.” This quote comes to us from Rilke’s essential and brief Letters to a Young Poet. You hear that? Quoting poets will get you laid.

Poets dating mega-celebs: it’s still happening and I’m still here for it. Who’s next?

You write some of the most thorough, well sourced, and substantiated work I've seen on here.