The Death-Defying Poetry of the Best Exorcist Sequel

Before you watch The Exorcist: Believer, revisit the best Exorcist sequel & the metaphysical poem at its black heart.

It’s the most wonderful time of the year: Spooky Season.

And because everything old is new again slash there are no new ideas in Hollywood (I wonder if studios’ refusal to pay and protect writers adequately has anything to do with this, she mused facetiously) this month a new reboot of a horror franchise staple is in theaters. The Exorcist: Believer is the latest installment of the series that began terrifying audiences back in 1973 with The Exorcist, written by William Peter Blatty and directed by William Friedkin.

Even if you haven’t seen this horror staple, you know it. You know the face of Regan, the child possessed by a demon. You know the filthy quotes. You know the staircase. The film routinely appears on lists of the best films ever made, let alone lists of the best horror films.

It would have been enough for the film to exist on its own, but this is America, so we went ahead and made five sequels, a television series, and a sixth sequel set to be released in 2025. God damn bless the USA.

Exorcist II: The Heretic is widely considered to be one of the worst films in the franchise (neck-and-neck with 2004’s Exorcist: The Beginning at 11% on Rotten Tomatoes. Why, Stellan Skarsgard, why?!) But The Exorcist III is the true spiritual sequel to the original, as it was written and directed by Blatty himself. Deeply literary, slow-burning, and weird in the best ways, the film also has a poem about death at its unrepentant heart.

Cutting Through the Confusion

There’s plenty to be confused about at the outset of this film: major characters have been recast and 15 years have elapsed since the events of the first Exorcist film. In this third installment, Lt. Kinderman is played by none other than George C. Scott (he is unbelievably good, better than the film even deserves) and Father Dyer is played by Ed Flanders of St. Elsewhere fame. The issue of Father Damien Karras, played in this film and the original by Jason Miller, is more complex. He’s here in body if not in soul, at least for most of the film.

*Spoilers Ahead*

One of the film’s weaknesses is also its major strength: the Gemini Killer’s deranged monologuing. Gemini is played with deranged perfection (and I mean perfection) by Brad Dourif. If you don’t know Dourif from Deadwood, The Lord of the Rings, or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, you might know him as the voice of Chucky from the Child’s Play franchise.

The Gemini Killer is a serial killer who is dead at the film’s outset, as is Father Karras. Though Dourif’s twisted explanation of how the 15-years-dead Gemini Killer came to inhabit the body of the 15-years-dead Father Karras is helpful in that it makes things clear, that much backstory crammed into a monologue is bad writing, plain and simple. The good news is that Dourif is compulsively watchable, so much so that I stopped folding laundry while he was on screen (and I’ve seen this thing at least 3–4 times before). You just can’t look away.

Sometimes Dourif’s face is on screen when Lt. Kinderman is speaking with the patient in Cell 11, and at other times it’s Miller’s. Sometimes the patient speaks in one voice or another, or in the voice of the demon Pazuzu revealing the tortured “legion” that gives Blatty’s novel—the basis for this film—its name.

Around the 38-minute mark, we hear a poem in voiceover. Which poem? And who’s reciting it?

A Holy Sonnet, Remixed

The poem that Patient X (the body of Father Damien Karras inhabited by the Gemini Killer and the demon Pazuzu—ain’t horror great?) recites in The Exorcist III is John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet X.” The “X” refers to the poem’s most commonly accepted placement as number ten in the poet’s 19-poem sequence of Holy Sonnets or “Divine Meditations.”

Donne (1572–1631) was a metaphysical poet, meaning that he was one of several poets alive and writing in the 17th century who was fond of using complex figures of speech or “conceits,” and was interested in infusing poetry with new philosophical ideas.

Here’s the poem quoted in the film in its entirety:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery. Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell, And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then? One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

The poem alludes to 1 Corinthians 15:26, i.e., “The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.” Donne’s poem deflates death by asserting that it is only a “short sleep” after which point we will “wake eternally” in a Christian worldview. Death, the most terrifying aspect of life, is not to be feared when there is eternal life to look forward to, or so says the poem.

But we don’t get the whole poem in the film, just an excerpt. But the lines of this excerpt are nonsequential in the original. In other words, this is a remixed sample. Here are the lines we hear in voiceover in The Exorcist III:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so.

Though soonest our best men with thee go,

rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.

But those thou dost thinkest thou dost overthrow

die not, poor Death, nor canst thou kill me.

We get the entire first couplet (a masterpiece, so well done there, Blatty). Then we get a bit from the middle (lines 7–8), then we get lines 3–4. But even here, it’s not a direct recitation: there’s some clunking around with the antiquated language. Line 3 in the original (“For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow”) becomes “But those thou dost thinkest thou dost overthrow.” The original is not in a strict metrical form, but there’s something about the double “dost” that mars the sound of Donne’s original, as well.

Is this supposed to be a third voice… not the Gemini Killer, not Karras, not Pazuzu, but someone—or something—else?

But of primary interest is the way the film uses the word “me” in line 4. In the original, we take this to mean the speaker, ostensibly a human man. Death cannot kill me, he seems to say, because I am eternal and will achieve eternal life in heaven.

In The Exorcist III, the voice comes in the darkness of the cell in which Patient X is restrained. But it doesn’t seem to be emanating from the prisoner himself. It sounds a bit like Karras, but it’s not clear. Is this a failure of voiceover? An intentional choice? Or is this supposed to be a third voice… not the Gemini Killer, not Karras, not Pazuzu, but someone—or something—else? Is this the voice of the devil himself?

If this is the case, then the idea that Death can’t kill the devil, that evil is eternal, is terrifying. The certainty that Donne has of Death’s eventual demise is dashed in this interpretation. Sure, we may surmount death, but what about eternal hell and pain, the stuff of George C. Scott’s powerhouse monologue near the film’s end:

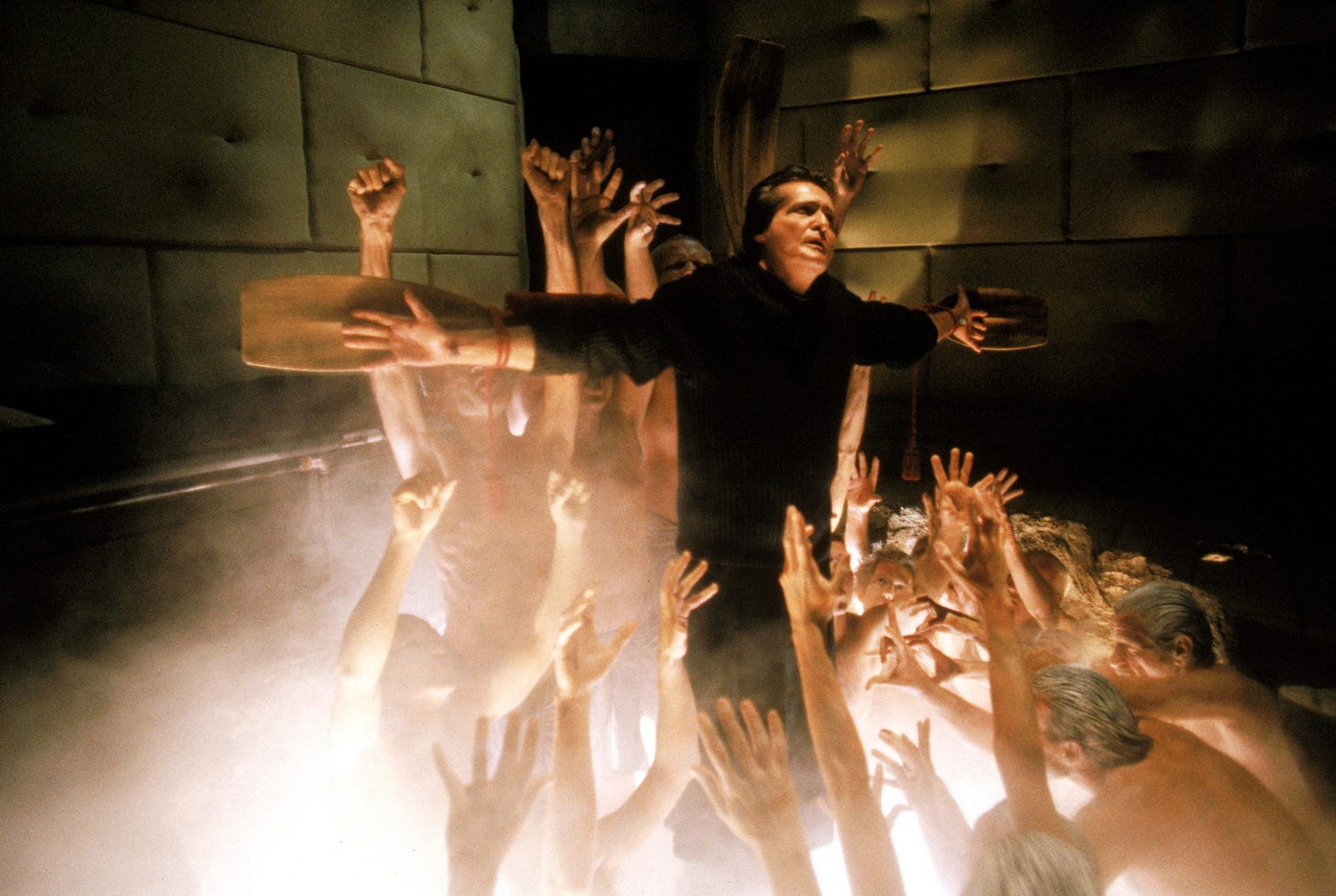

This I believe in... I believe in death. I believe in disease. I believe in injustice and inhumanity, torture and anger and hate... I believe in murder. I believe in pain. I believe in cruelty and infidelity. I believe in slime and stink and every crawling, putrid thing... every possible ugliness and corruption, you son of a bitch. I believe... in you.

Like Donne’s poem, the film agrees that death is not the end. But the idea that what comes after may not be heavenly eternal wakefulness, as Donne would have it, but a terrifying and endless nightmare, as Blatty would… that’s high horror, indeed.

Related

Spooky: Edward Scissorhands Was Programmed on Limericks

They say that God created man. The man God created, in turn, sometimes dreams of playing God. Thus the possibility of creating life from nothing is one of the most important veins in horror, science fiction, and other genres. Its transgression has thrilled us for eons, from the golem of Jewish folklore to

January Embers, Part II: The Big Lesson of a Little Poem in It: Chapter Two (2019)

Welcome to the third of four creepy Halloween posts featured at PopPoetry this month! If you missed Part I of this two-part post on the haiku at the heart of the 2017 remake of Stephen King’s It, check out January Embers, Part I here. If you watched

American Horror Story: Cult, Shelley, and the Patriarchy

When I finally finished American Horror Story: Cult on Netflix, then promptly went to sleep and dreamed that a man who looked not unlike Donald Trump was chasing me with a knife. I did it to myself, watching it so late at night. But it might also be true that Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk did it to me. I admire the way that this season was able to tap into contemporary American fears about politics, sex, and violence in a way that felt contemporary.