Decades Before Greta Gerwig's Barbie, This Poet Made Subversive, Feminist Art About the Iconic Doll, Too

Denise Duhamel's Kinky (1997) is receiving new—and deserved—attention as Barbie movie mania continues..

What is pop culture?

You’d think that someone like me would have a ready answer for this question. At PopPoetry, I mainly focus on television, movies, and popular music. But pop culture and its shadow extend much farther than those three types of media alone. Video games, for example, are absolutely a part of the pop culture landscape. But other aspects of popular culture are less clear in their designations. For example, are sports a part of popular culture? What about toys?

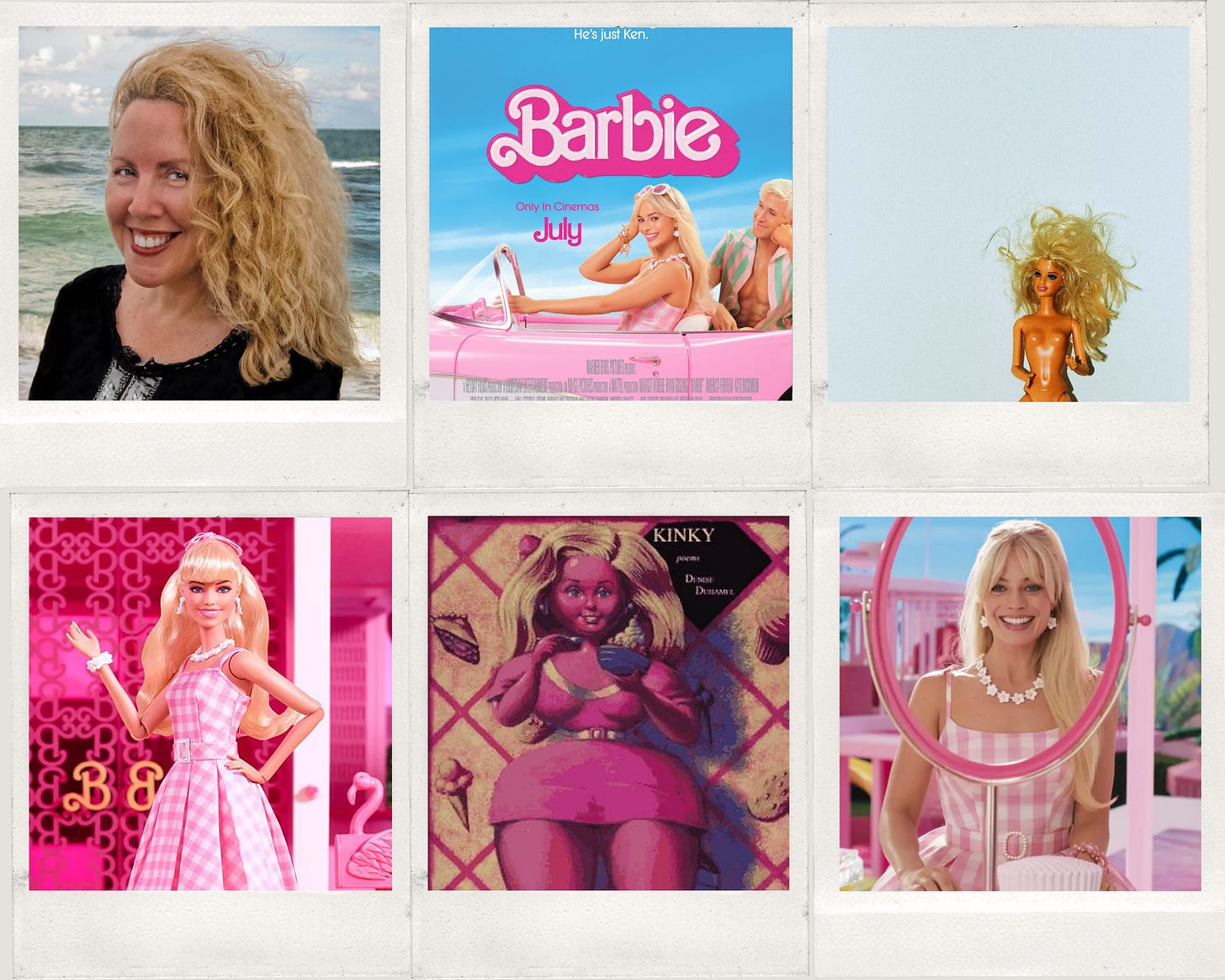

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie has dominated the pop-culture landscape for weeks now. It has made an impression on everything from fashion to advertising to memes and more. Undoubtedly, Barbie, of all toys, would qualify for inclusion as a piece of pop culture if any toy would. Since the 1950s, Mattel’s iconic and controversial doll has been in the hands of children and on the minds of people both young and old in America and beyond. But Gerwig isn’t the first person to create art inspired by Barbie. Lately, the incredible Denise Duhamel has received renewed attention for her 1997 book of poetry, Kinky, which was inspired by Barbie and all of her wonderful weirdness.

Published by Orchises Press, Kinky contains poems that are—you guessed it—bizarre and erotic in the best way. But more than their kink, Duhamel’s poems are feminist, funky, and philosophical. She envisions the doll in a range of situations that would make Mattel executives blush or run for the hills.

Of the book’s title poem, Duhamel had this to say in her recent Barbie film-spurred interview with the FIU News:

I have nieces, one of whom just turned 40, and I was visiting them when they were 6 and 4. One of their doll’s heads popped off, and their father thought it was the most hilarious thing. They had a Ken, and he popped Ken’s head off and put it on Barbie’s body, and the kids were screaming. So in another poem, Barbie puts Ken’s head on her body and Ken puts Barbie’s head on his body to try and get into each other’s heads. My point was, ‘Can men and women really understand each other?’

Whatever I was thinking about, I could just put Barbie in that situation, and it became a way to make feminist statements that were funny. There’s a wink and a nod in the poems. When I look back at the thinking process, it was just one foot in front of the other, or one high heel in front of the other. I just kept going.

In my poems, Barbie is never in Barbieland [an alternate reality in which the dolls are in charge]. Instead, she’s being played with or torn apart, bitten by a dog, melting on a stove, just all sorts of abuse. As a writer, I started off not liking her very much. [That dislike] was about beauty standards and the ‘Barbification’ of culture. It was about certain archetypes of women.

Accompanying the interview is a delightful image stolen from the Barbie film has been doctored to include Duhamel’s face badly photoshopped over Margot Robbie’s face as she drives her pink car down the freeway.

This meme-like image delights me. Seeing one of contemporary American poetry’s well-known luminaries dropped into the current cultural zeitgeist, even in a way that is silly and purposefully inexpert, is exciting. One can only hope that such attention will mint new readers for Duhamel specifically and poetry more generally.

Duhamel’s Barbie poems are blunt, often short, and panoptic in their appraisal of Barbie and her symbolism. Take Duhamel’s “Buddhist Barbie,” for example:

In the 5th century B.C. an Indian philosopher Gautama teaches "All is emptiness" and "There is no self." In the 20th century A.D. Barbie agrees, but wonders how a man with such a belly could pose, smiling, and without a shirt.

Not only are the poems about a trenchant piece of pop culture, but they also speak to the reader in a voice that is frank and straightforward. These poems have teeth, but still speak softly and seductively about power, sex, and embodiment. They’re ideal companions to the conversations we’re having about these topics today in the wake of the Barbie film’s release, and exactly the kind of poems that can be enjoyed by both literary types and those who are new to poetry alike.

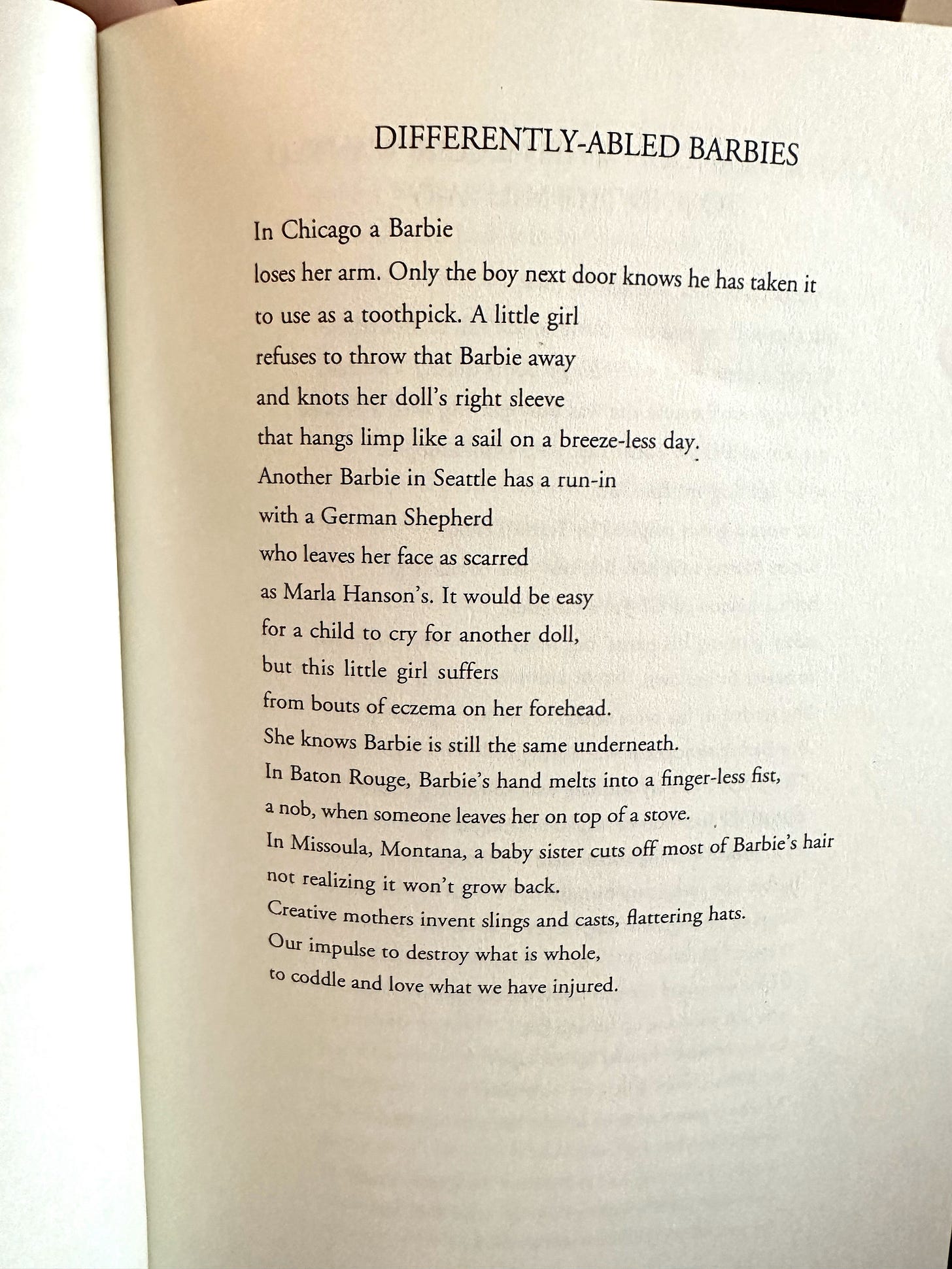

Some of the poems are of their time in a way that hasn’t aged quite as well as others: “Oriental Barbie” and “Differently-Abled Barbies” come to mind. But even these poems have the ring of critique to them: Duhamel attempts to show how this antiquated language damages and disappoints those it was once aimed at, how poorly we treat those who we only pay lip service to.

Kinky is now meeting another generation of readers through Dustin Brookshire’s Never Picked First for Playtime, an homage that depicts a doll holding a copy of Kinky on its own cover. These au courant poems tell a different side of the story of Barbie—one from the perspective of gay men. “Pandemic Barbie,” for example, exalts the “little boys who, in secret, love her.”

Duhamel said that Gerwig hadn’t reached out to her in any way as she worked on the film, and she’s unsure if she has ever read her book. I hope that if she hasn’t, Greta Gerwig takes the opportunity to look back at the lineage of American creatives who have been reinterpreting our most controversial doll for decades and picks up a copy of Kinky for herself.

I missed Barbie at the theaters (I’ve got an excuse: my 11-month-old future Barbie skeptic) but can’t wait to check it out on the small screen—right after I finish my reread of Kinky.

I enjoyed your PoPoetry article! It was fun and light, and made me think of your Barbie Corvette parked in my garage! 🩷