Blink & You'll Miss the Poetry Lesson Hidden in A Quiet Place

Before You Check Out A Quiet Place 2, Take a Deeper Look at the Original

You’re reading PopPoetry, a poetry and pop culture Substack written by Caitlin Cowan. You can learn more about it here. Check out the archive to see other TV shows, movies, and films whose intersections with poetry I’ve covered. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, subscribe so you won’t miss a post!

Alright, y’all: I took myself to the movies this week and it’s finally time to hit send on a post I’ve been looking forward to writing for ages.

It’s been a good summer for horror films so far. Saw franchise offering Spiral came out on May 14, and The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It (AKA The Conjuring III) arrived on June 4. Just before that, the sequel to A Quiet Place, the 2018 horror film beloved by critics and fans alike, crept into the world with neither a bang nor a whimper.

But before you run out to see the sequel if you’re so inclined, take a second look at this smart, tender scene from the original recipe horror flick that can teach us a thing or two about poetry. Yes, really!

Written, directed, and starring The Office’s John Krasinski in a role that felt truly severed from his camera-mugging Jim Halpert, A Quiet Place still feels like a revelation. Patient, sparse, and beautifully shot, the film is brimming with love, even as monsters threaten to eviscerate everyone on screen.

For the uninitiated, the central premise of A Quiet Place is that the world has been beset by monsters that hunt by sound. They’re not able to see or smell humans, but they can hear even tiny noises. Those who have survived have converted their lives into spaces of ultimate quiet, and devise ingenious ways to cover the sounds that they do make.

Life goes on: the Abbott family at the center of the film raises their children and educates them about both academic subjects and matters of survival in the terrifying new world they find themselves in. And during one “school scene,” we’re able to spy some poetry.

What is this poem?

The poem written on the board in the background of the school scene of A Quiet Place is the first four lines of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18. I’ve written about Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 before, and I wasn’t kidding about this poem appearing everywhere. It’s one of the Bard’s most famous sonnets—if not the most famous—but in A Quiet Place, we don’t hear the poem read aloud.

The characters don’t even reference the poem with a glance or a piece of ASL (American Sign Language, which the cast uses fluently) dialogue. Instead, the lines are allowed to loom there behind Evelyn Abbott (Emily Blunt) as she works on a bit of math with her son Marcus (Noah Jupe). [Though she doesn’t appear in the scene above, the Abbotts’ daughter Regan (resplendent deaf actress Millicent Simmonds) is at the core of this film in so many ways.]

But the text of the poem is clearly visible, as are some markings that appear above the words themselves in between the lines. These marks are prosodic markings that indicate the way the language sounds without actually making a sound.

It’s so clever it makes me want to scream. But I won’t.

What is prosody?

If you’re an expert, skip ahead, but for the rest of us, read on!

Much of our time as readers of poetry is spent thinking about the overt meaning of the words included in the poem (text) and what those words might mean on a subterranean or deeper level (subtext). But there’s a whole other aspect of poetry that you might not be as familiar with or as attuned to, depending on your level of poetry interest or expertise: prosody.

Prosody refers to the soundscape of poetry. This encompasses everything from the actual sounds that letters and words make in your head when read silently or in your ears when read aloud to the length and weight of syllables and syllable patterning.

Why do poets do these things? Because we can. Literally.

Sound is just one more way that poets can express themselves: a color in our crayon box. And here’s a really big and important fact about poetry: form and content have a relationship. They’re going steady. I think form might even propose.

Think about it this way: a poem that has lots of long “O” sounds can start to sound mournful, like moaning. A poem with heavy “s” sounds can put us in mind of rain, or rivers. Similarly, when lots of short, heavy words are placed one right next to the other, the sound can be forceful, which draws extra attention to that section. The fascinating relationship of form to content in poetry (and in art more generally) could be studied for a lifetime: there is much richness in this idea.

Though for some, poetry might feel like a “quiet” pursuit that lives inside silent textbooks, I’ve written about how poetry has always and continues to live vibrantly off the page and in our ears. But for the characters in A Quiet Place, poetry has to stay silent, or its sound has to be felt and understood differently. Teaching her son how to enjoy a verbal art form quietly is a stroke of genius for Blunt’s character.

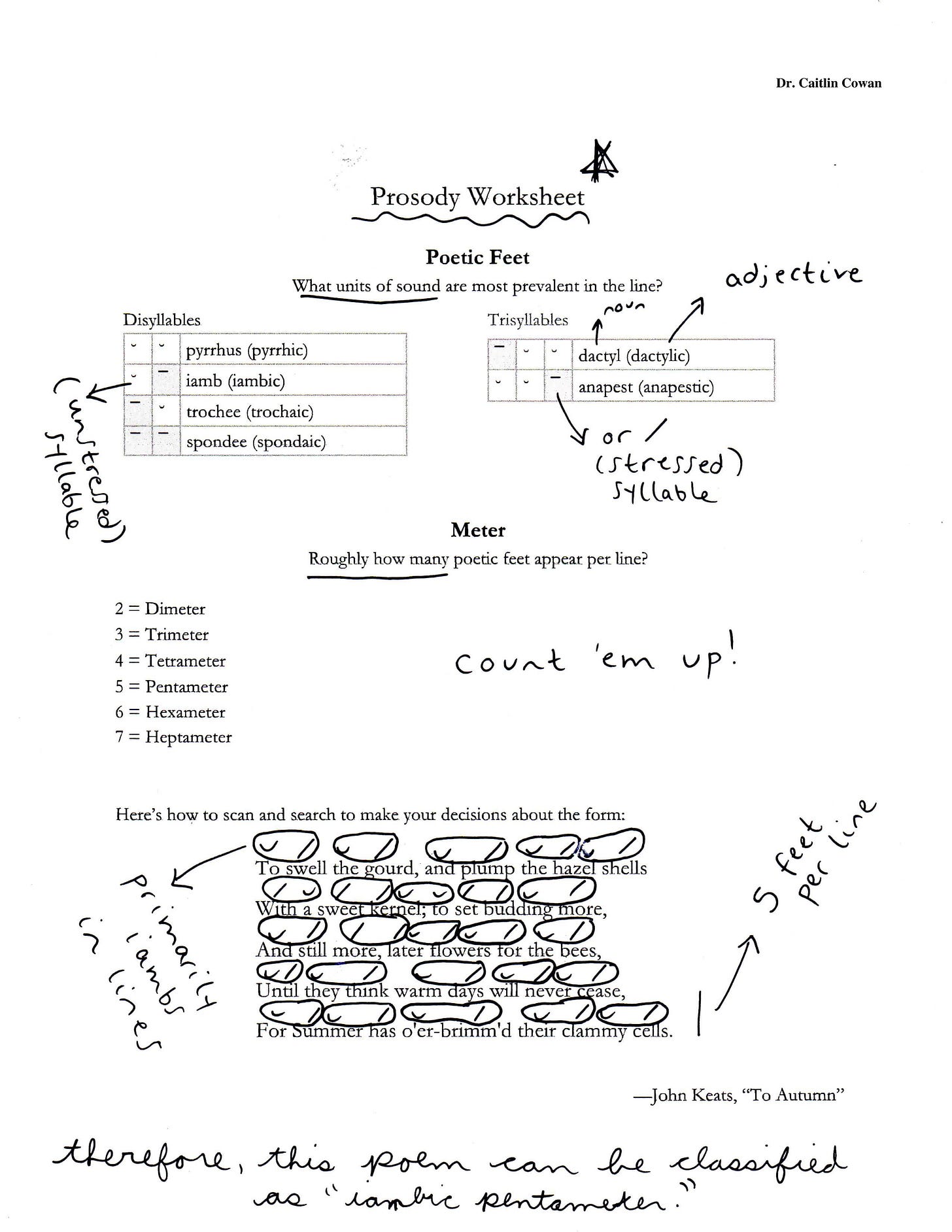

The markings that (ostensibly) Evelyn has placed over the words of Shakespeare’s poem in the film indicate where the stress falls on each word. We call these markings and this creation of this kind of sound map scansion. Typically, a forward slash (/) indicates a stressed syllable and an “x” or breve symbol (˘) indicates an unstressed syllable.

English has two kinds of syllables: stressed and unstressed. A stressed syllable has more weight and length to it. For example, the word “compare” is pronounced “come-PARE,” where the second syllable is a bit heavier than the first. We don’t pronounce this word as “COME-pare.” That sounds wrong, right? But for non-native speakers and many others, this “sounds right, sounds wrong” test isn’t useful. Dictionaries generally provide guidance on where the stress falls in a given word, which is helpful, and thanks to the internet, it’s easier than ever to hear audio samples of word pronunciation.

But what about monosyllabic words like “I”? How are they stressed or scanned?

The answer is: it varies. This is where things get really interesting. Polysyllabic words are easy enough to scan, but when those words are strung together with various monosyllabic and other polysyllabic words, we have to look at things from a more zoomed-out perspective to make decisions about how to interpret the meter, or pattern and number of syllables per line.

There are several common poetic feet, or small groupings of stress patterns, that tend to occur in poetry. We count how many of the most common foot occur in a line in order to make a decision about the meter:

For example, iambic pentameter is a kind of meter that uses five iambs per line, and trochaic trimeter makes use of three trochees per line.

Think that sounds confusing? Japanese has four different kinds of syllables: and they’re based on pitch rather than stress or weight. Whew!

Iambic Pentameter

Iambic pentameter is by far the most common meter in English poetry, and it’s often said to mimic the natural cadence of human speech in English. That’s pretty cool, if you ask me. It’s also a shrewd choice for the background of a film where humans mustn’t speak to save their own lives. It feels almost like an act of defiance.

Let’s scan the opening of Sonnet 18:

x / x / x / x / x /

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

x / x / x / x / x x

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

/ / x / x / x / x /

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

x / x / x / x / x /

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Evelyn’s scansion here is slightly different and adheres strictly to perfect iambic pentameter. Yeah, good metrical poetry also varies from its own meter in order to provide variety and richness. I forgot to mention that.

It might feel maddening to consider, given the intricacy of what we’ve just covered. But you wouldn’t like to go on a date with someone who drones on in the same exact speech patterns for minutes on end, would you?

I’ve scanned the passage myself above, and I tend to read the word “temperate” as a dactyl (a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables), and feel that a spondee (two stressed syllables in a row) better reflects not only a natural reading but also the strength of rough winds in the third line.

The vast majority of these syllabic units are iambs, which is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable, and there are typically five iambs per line, which is how we arrive at a determination of iambic pentameter.

Why is this interesting?

The backdrop of scanned poetry is a coy nod to the art form’s many lives and qualities: percussion, tone, meaning. Overall, the film shows off many brilliant ideas that the Abbott family has about how to thrive in silence. They play with soft game board pieces, use leaves instead of plates, and build a (horrifying) and ingenious, soundproof, oxygenated box for a newborn baby to nestle inside when it’s crying. It seems that Evelyn Abbott has also found an ingenious way to teach the joys of poetry off the page even when no one can make a sound.

There are many ways to feel the pulse of prosody. You might squeeze your leg on a stressed syllable and release it for an unstressed syllable. You could nod your head, letting it dip deeper for stressed syllables.

And let’s not forget the choice of poem as well, and its overall project of comparing a beloved’s beauty to the changing seasons and intractable forward motion of time:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

This is a love poem, and deep, deep love abounds in this film. The love between Evelyn and Lee is overt, but the movie is primarily a meditation on parental love and responsibility. “Who are we if we can’t protect them?” Evelyn asks Lee in one of the rare scenes where she speaks aloud.

It also explicitly discusses the march of time, which Blunt’s character discusses with her son in the school scene itself:

(In sign language and mouthed)

He just wants you to be able to take care of yourself.

…to take care of me…

…when I’m old…

…and grey…

…and I have no teeth…

Whenever I watch apocalypse media, I’m always stunned by how much might still be left in a blasted world.

Pop Palate Cleanser

Because we’ve revisited Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 before on PopPoetry and, as always, to temper the overwhelming presence of old-dead-white-guy representation in poetry that makes its way into popular culture, I’d like to highlight the work of a brilliant poet friend: Chad Abushanab. His book, The Last Visit, was selected to win the Donald Justice Poetry Prize by Jericho Brown in 2018.

Chad certainly fits the bill for this post: I happen to know that he’s a massive horror fan in addition to being an incredible poet who often writes formal poetry that uses rhyme and meter skillfully.

Listen carefully for the pulse, the heartbeat of the metrical poems he reads in the video below, beginning around 21:03.

You can buy The Last Visit here or find local bookstores that have it in stock on IndieBound. Find our more about Chad’s work on his website.

P. S.

Jada Pinkett showed the world what appears to be a new Tupac poem on what would have been the rapper’s 50th birthday. I wonder if his “nothing gold” refrain was inspired by Frost or The Outsiders… or both?

Pride Poets are doing something I’m very passionate about: bringing poetry directly to the people through the Poetry Hotline.

Irish poet Paul Muldoon will edit a book of Paul McCartney’s song lyrics. The latter Paul was apparently a recent guest in the former Paul’s songwriting class at Princeton.

And if you’re a horror junkie like me, other summer horror highlights include:

The Forever Purge (July 2)

Escape Room 2 (July 16)

Shyamalan’s Old (July 23)

Don’t Breathe 2 (August 13)

The Candyman reboot (August 27)

Happy screaming! (Shhhhhh….)